Preparedness activities prepare to handle an emergency caused by a disastrous event and reduce the effect to the road function.

Preparedness refers to the activities that enhance management skills in order to reduce the impact of a disastrous event on the road by responding appropriately and recovering quickly. Preparedness is a step-by-step, time-based process for increasing the maturity level required to meet all possible disasters in coordination with national, local and regional organizations and agencies responsible for managing the road. Preparedness activities occur before an emergency transpires.

Preparedness consists of three elements: forecasting, preparing, and inspection and training. Forecasting is the anticipation of natural disasters and the identification of emergencies affecting people, society and roads. Preparing is the use of people, goods, money, information and systems in response to anticipated emergencies. Inspection and training provide effectiveness for preparedness 1. Forecasting should correspond to the assessment of risk. Risk-based impact projections, based on appropriate consultation with relevant stakeholders, are key. Consideration should also be given to the lower limit of impact projections in terms of addressing potential risks. Preparing includes the development of a disaster prevention manual including emergency response policies, plans and procedures; development of a disaster prevention system; management and training of human resources; and disaster forecasting and warning. It is also necessary to revise the manuals as needed to respond to future changes in the risk environment. It is also important to stockpile fuel and food, and to secure recovery equipment and materials. Naturally, consideration must be given not only to those engaged in road management, but also to those who use the roads. It is important to carry out inspection and training on a continuous basis.

Preparedness requires the establishment of agreements in advance with road users and roadside communities, both internal and external to the organization, for both forecasting, preparedness and inspection/training.

In order to prepare for disasters, coordinated action is essential. This requires close coordination among communities involved in disaster management. It is no exaggeration to say that disaster preparedness is a matter of planning for this community coordination.

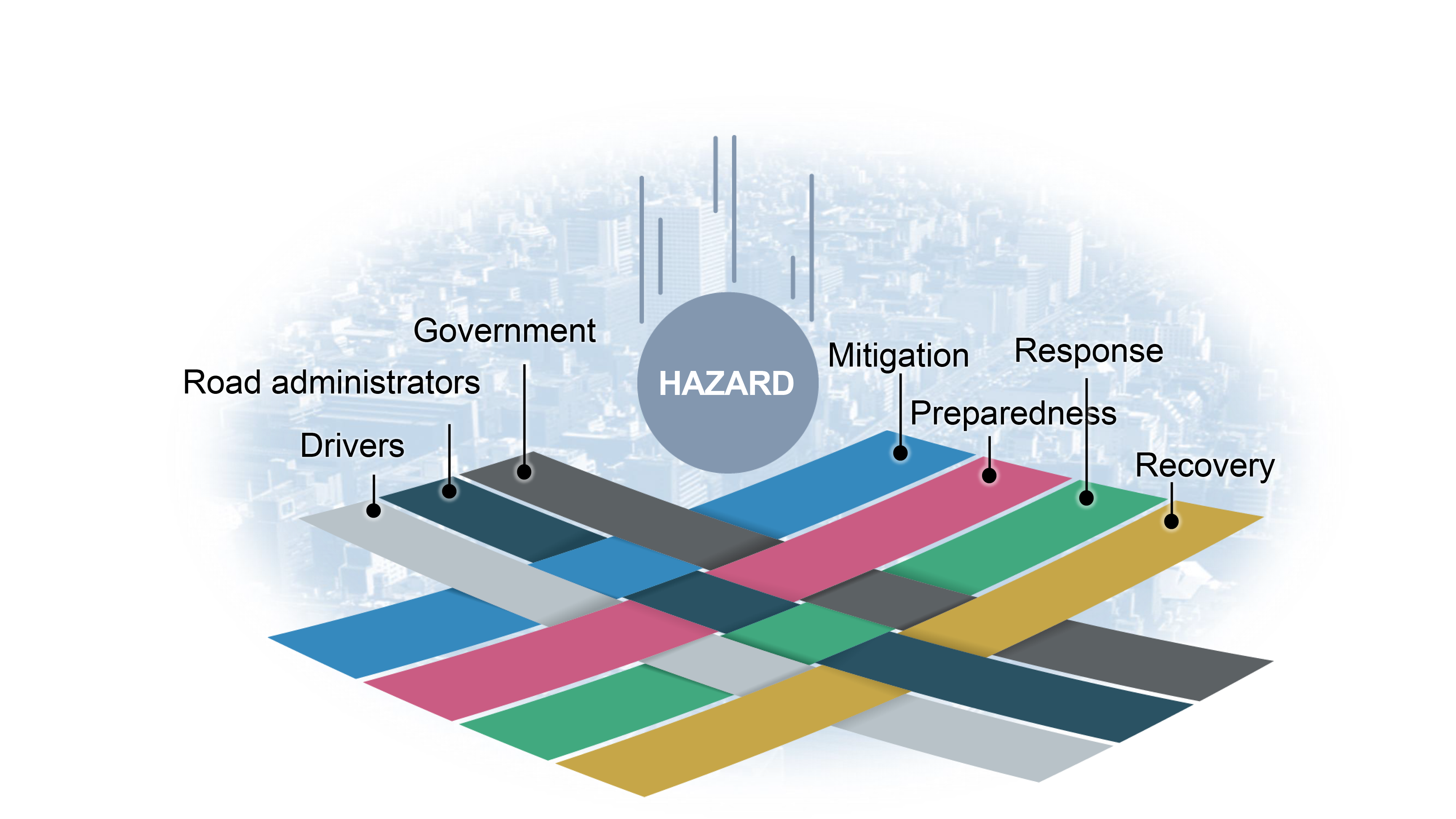

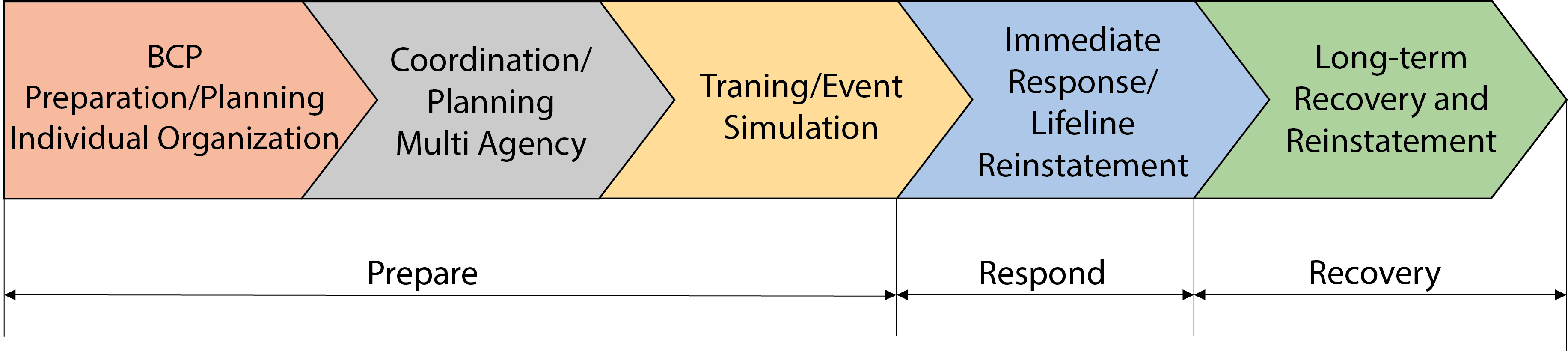

A disaster management plan establishes community networks and arrangements to reduce the risks associated with disaster preparedness, response and recovery. In particular, preparedness is one of the key elements of the disaster management cycle and needs to be interwoven with the warp and woof. In other words, it is important to work closely with each other in accordance with their respective disaster management roles, responsibilities, capabilities and capacities. The warp and woof threads here are generally as follows like shown in Figure 3.1.

(1) Action plans for all phases of disaster management (prevention, preparedness, response and recovery) based on the development of plans and arrangements based on risk assessment.

(2) Coordination with road managers, national and local governments, and driver cooperation in all phases of disaster management (prevention, preparedness, response and recovery).

Figure 3.1 Disaster management coordination

This chapter discusses the following items in the preparatory phase of disaster management and details their considerations.

There has been a growing demand to maintain roads functionally to ensure the role of emergency transportation roads and to minimize the time of disruption of supply chains. Therefore, "business continuity planning," which focuses on securing road functions, is becoming increasingly important as an activity to further enhance road function disaster preparedness.

Natural disaster hazards include floods, volcanoes, earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides and so on. Disaster management for natural disasters begins with the identification of natural disaster hazards and their appropriate assessment. In other words, it is important to identify the hazard and assess its risk level. Forecasting technology for all hazards has advanced, and in many cases, the results of damage prediction are compiled into hazard maps that are incorporated into disaster management.

Early warning information provision currently includes those for floods, earthquakes, avalanches, tsunamis, tornadoes, landslides, and droughts. Some of the road authorities provide their own early warning systems for specific disasters listed above. The objectives of early warning information provision can be divided into two categories: damage deterrence and damage impact reduction. The purpose of damage suppression is to minimize the occurrence of disasters by providing information on the possibility of disaster occurrence in advance and preparing for it. This includes rainfall information and typhoon forecasts. On the other hand, "damage impact reduction" is to prepare for the damage that has occurred in order to cope with the situation and reduce the impact of the disaster afterward. It corresponds to the damage prediction immediately after the earthquake. It is desirable to provide both types of early warning information, but it is necessary to consider providing information according to the situation in each country.

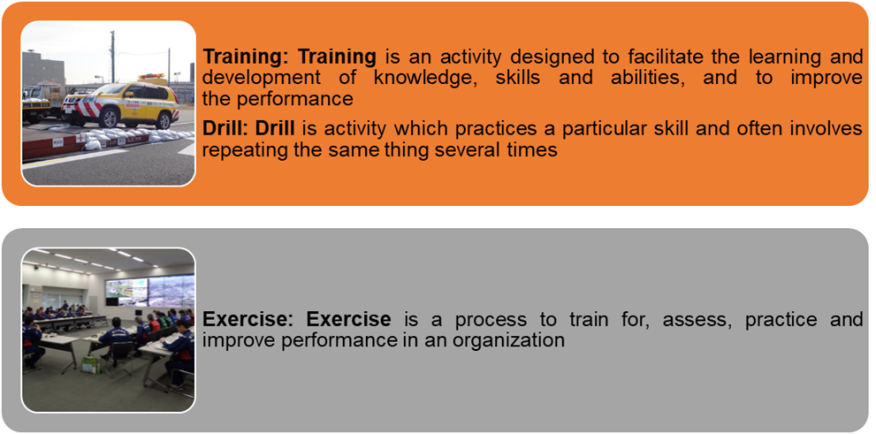

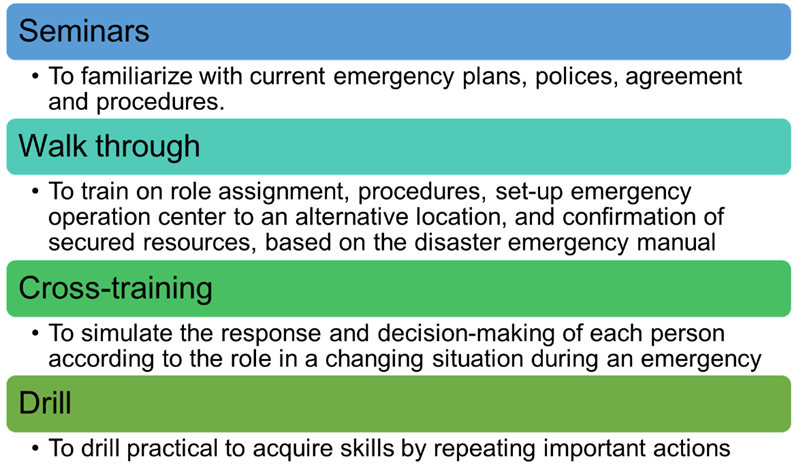

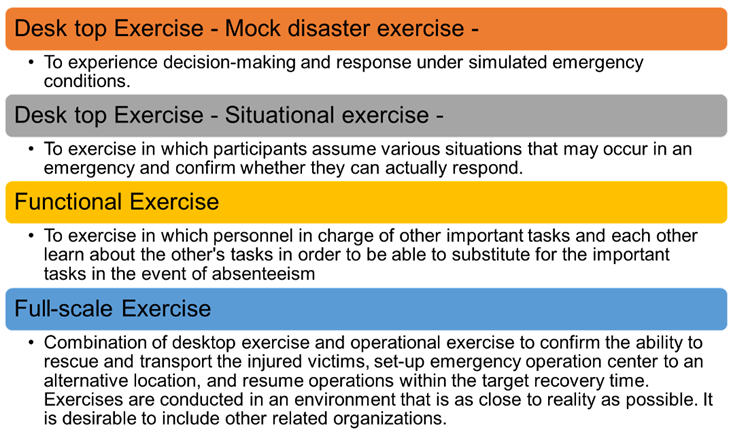

In responding to emergencies, it is essential to develop a business continuity planning strategy for various emergencies based on an "all-hazards approach", taking into account all organizations involved in road management, including the national government, local governments, road management companies, and related partner companies. To do this, it is necessary to understand the business continuity capabilities of each organization, consider how to cooperate with each organization in business continuity, and work with each organization to increase its business continuity capabilities. This is discussed in the section on "Business Continuity Planning. It is important to enhance the ability to respond to emergencies during normal operations. For this purpose, "Training (Drill)", and "Exercise" are important.

None of these preparatory considerations can be completed by road managers alone. They are all items that can be accomplished by working in cooperation with other organizations. It is necessary to respond in cooperation with stakeholders, such as the community within the road administrator, the community among road administrators, and customers.

Many road administrators have traditionally developed "disaster prevention plans" as an activity to enhance road disaster preparedness. The main focus of this activity is to minimize human and property damage and to maintain roads structurally. On the other hand, in recent years, there has been a growing demand to maintain roads functionally, for example, to ensure the role of emergency transportation roads and to minimize the time of disruption of supply chains. Therefore, "business continuity planning," which focuses on securing road functions, is becoming increasingly important as an activity to further enhance road function disaster preparedness.

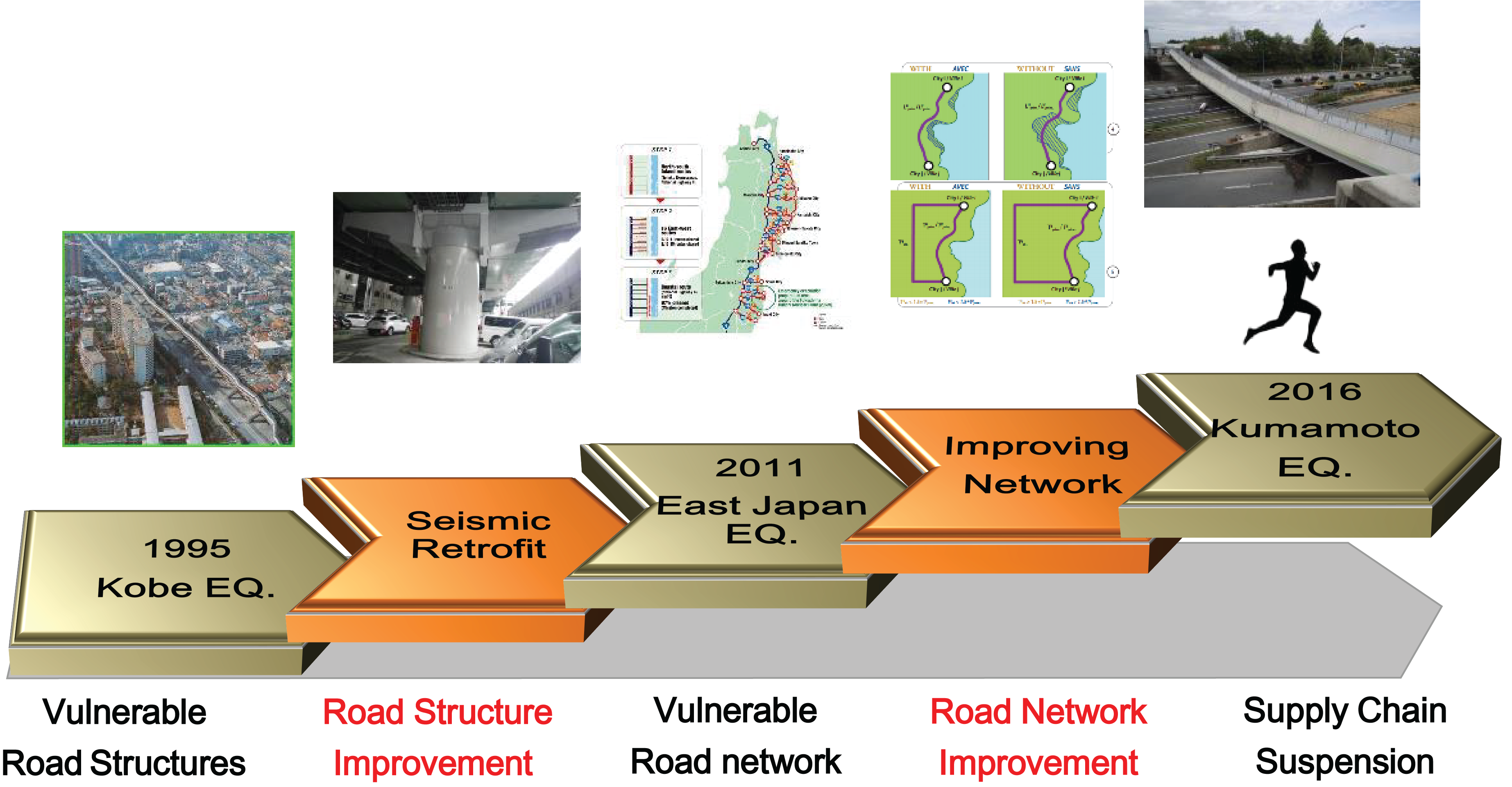

Figure 3.2-1. shows an illustration of the changes in stakeholder demands for earthquake disaster mitigation in Japan: in the 1990s, attention was focused on the seismic vulnerability of road structures, and around 2010 on the vulnerability of the road network, but in recent years, attention has shifted to the retention and continuity of road functions. In this way, it is clear that the expected role of roads in times of disaster has evolved over time.

Figure 3.2-1 Changing stakeholder demands for earthquake disaster performance in Japan

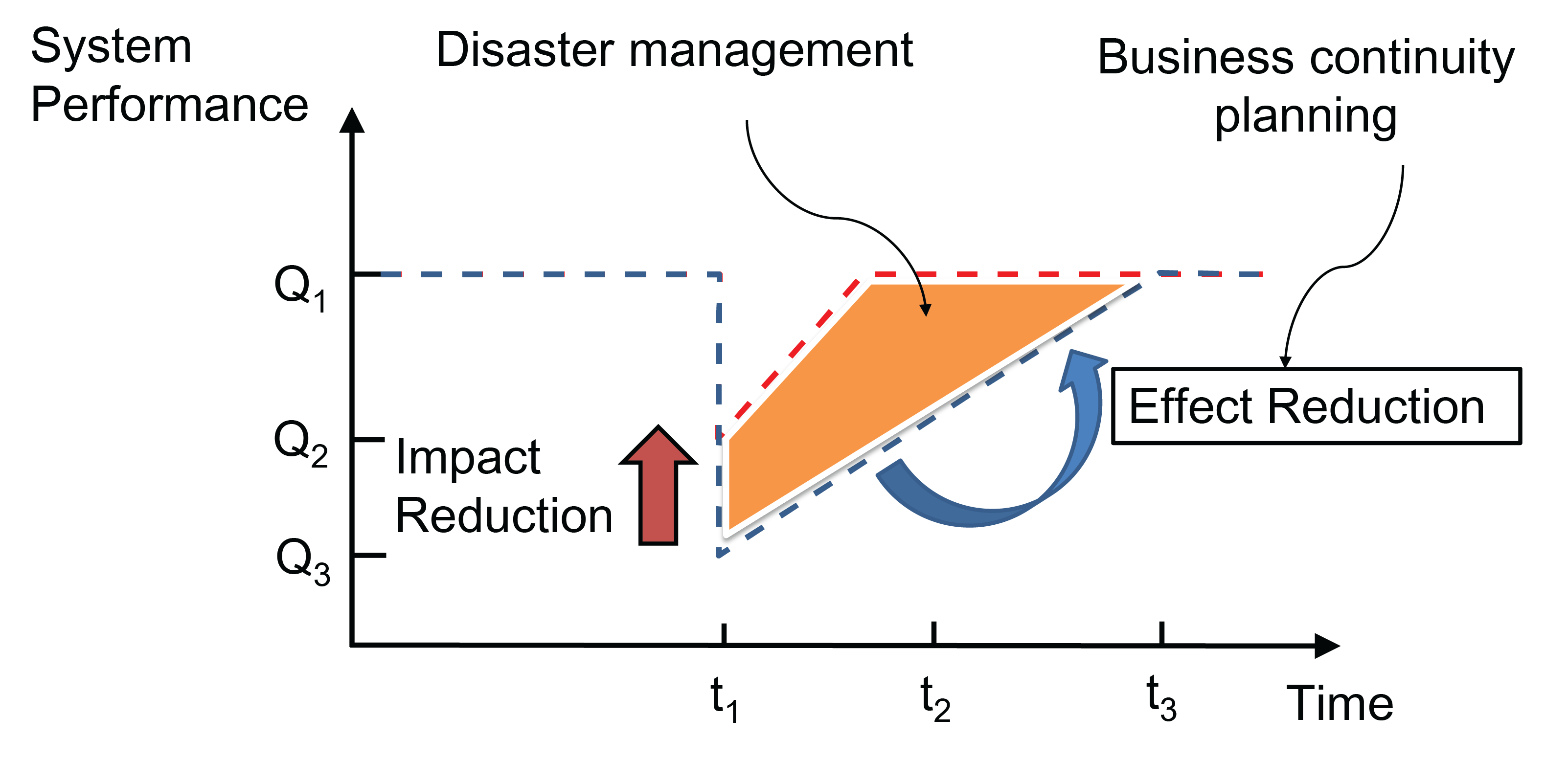

Figure 3.2-2. shows the role of disaster management in dealing with the loss of road functions due to disasters. Table 3.2-1. also compares the characteristics of conventional disaster management plans and current business continuity plans. Disaster management can be roughly divided into two categories: mitigation of the disaster itself and mitigation of the impact of the disaster. Conventional disaster management plans focus on the former, while business continuity plans include the latter.

Figure 3.2-2 The role of disaster management and its relationship to road performance

| Characteristics of conventional disaster prevention plans Minimization of human and physical damage | Characteristics of business continuity plans in recent years Further minimization of functional damage | |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Ensure safety of human life | Continuation and early recovery of critical operations |

| Indicators | Number of casualties | Recovery time and recovery level |

The following is a summary of issues that should be considered when developing a business continuity plan:

When formulating a business continuity plan, it is important to plan according to a timeline that includes cooperation with related organizations that are capable of responding to all disasters and cooperating with each other, using scenarios that assume various types of disasters.

In the event of a disaster, it is important to cooperate with related parties beyond the scope of daily operations. It is important to identify the organizations and tasks involved in disaster response, and to build cooperative and collaborative relationships based on this information in advance.

When responding to a disaster, it is necessary for everyone from the task force to the staff working on the site to have the same goal in mind. In order to maintain this consistency of action, it is important to establish a system of command and order and to develop information management tools. In addition, it is essential to coordinate with related organizations so that actions can be taken in cooperation.

It is necessary to constantly assess risks and plan pre-, during, and post-response measures according to the risks. In addition, it is necessary to prepare a variety of precautionary measures along the timeline, such as early warning information, pre-event road closure, and pre-notice road closure, depending on the risk level.

It is important to plan for the rescue and protection of road users who are stranded on the road during a disaster.

It is important to integrate elements of emergency management that are common to all hazard types and plan to fill in the gaps by complementing these common elements with unique individual elements specific to each hazard.

It is important to disseminate information on the road at all times and to build trust with road users. For this purpose, it is important to disseminate all kinds of information using all kinds of channels.

It is important to regularly review the business continuity plan using the latest risk information and to continuously improve the plan to ensure that it always addresses all risks.

In the event of a natural catastrophe or other disasters that seriously affects the functioning of roads, road managers need to ensure that the road functioning continues or is quickly restored, and that better restoration is carried out according to priority to avoid disruption of the supply chain and to support the recovery of economic activities. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to assess all possibilities of a major disaster, assume more severe situations, and consider in advance a business continuity strategy that is effective even in the case of damage caused by an unforeseen Disasters targeted by road administrators must cover events that affect all road functions, including natural disasters, pandemic disasters, and terrorism. This section outlines the business continuity plans that road administrators should prepare.

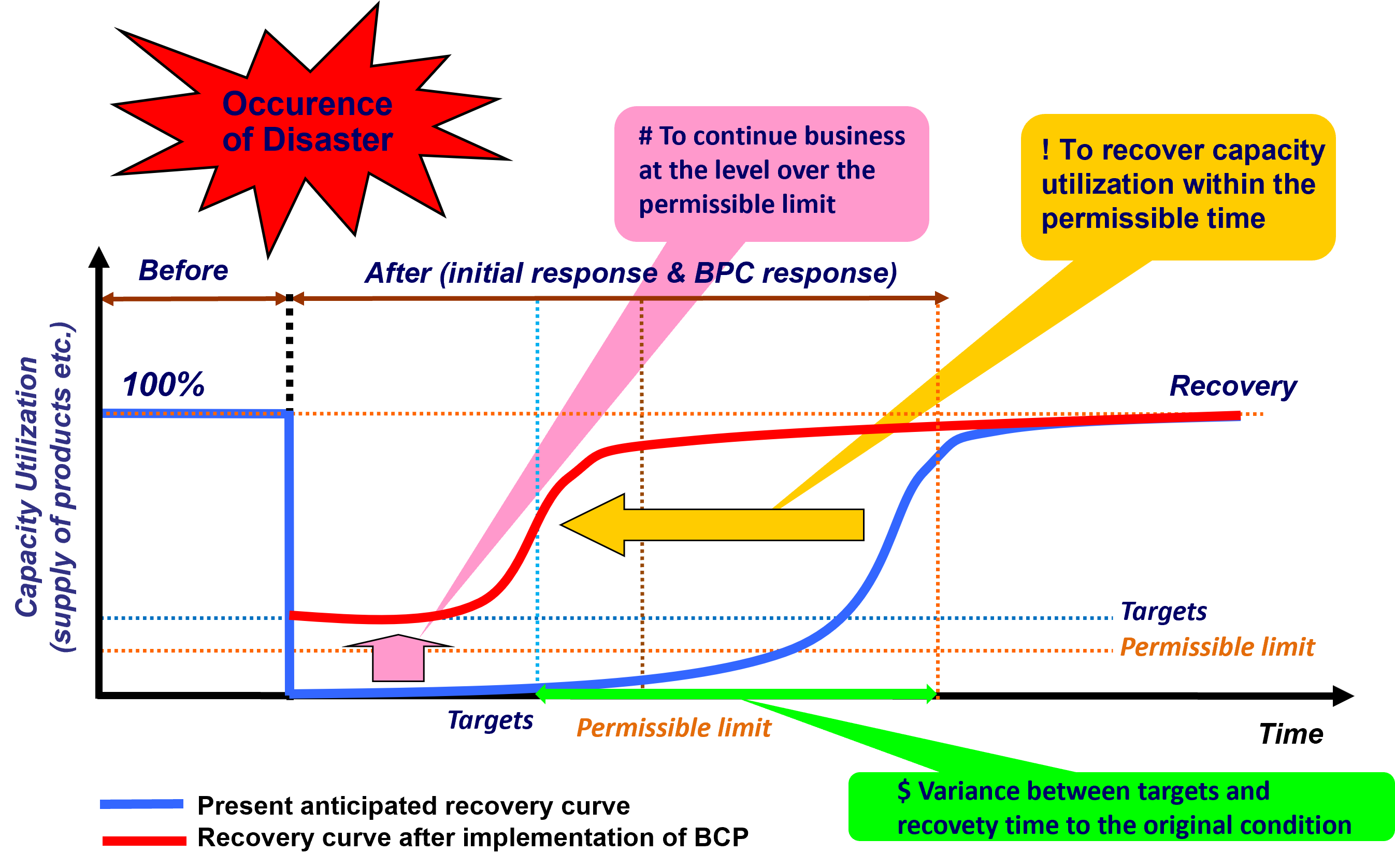

The BCP is a plan to ensure that important business operations are not interrupted in the event of unforeseen safety and security issues, such as natural disasters such as major earthquakes, the spread of pandemic diseases, terrorist incidents, major accidents, supply chain disruptions, and sudden changes in the business environment.

BCP is a plan that describes the policies, systems, and procedures to ensure that important business operations are not interrupted, or if they are interrupted, that they are restored in the shortest possible time.

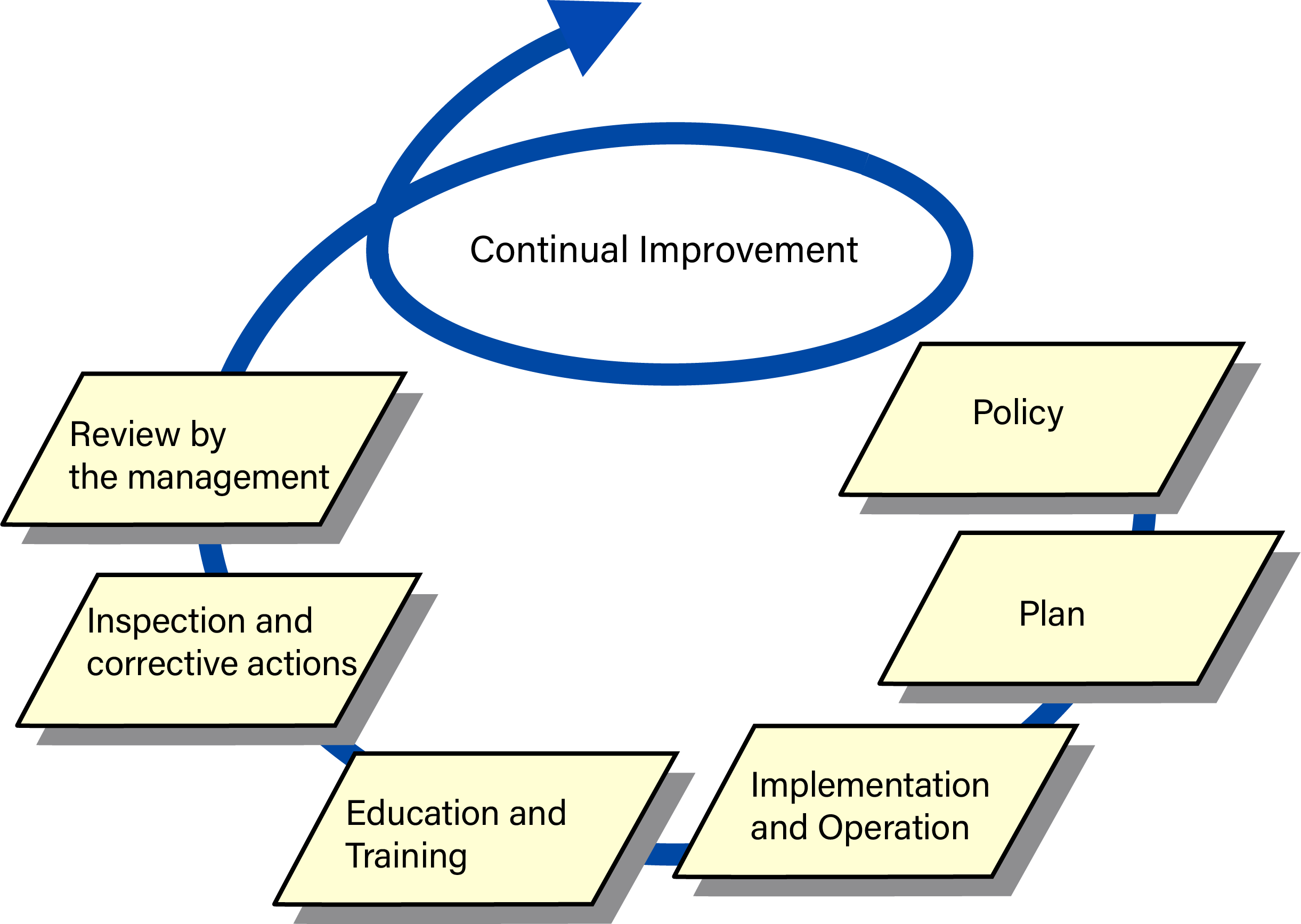

BCM refers to the management activities that are carried out during normal times, such as the formulation, maintenance, and renewal of BCPs, securing of budgets and resources to realize business continuity, implementation of preliminary measures, implementation of education and training to disseminate the initiatives, inspection, and continuous improvement. Management (BCM). Figure 3.2.1.1. shows the concept of business continuity planning 1.

Figure 3.2.1.1. Concept of business continuity planning

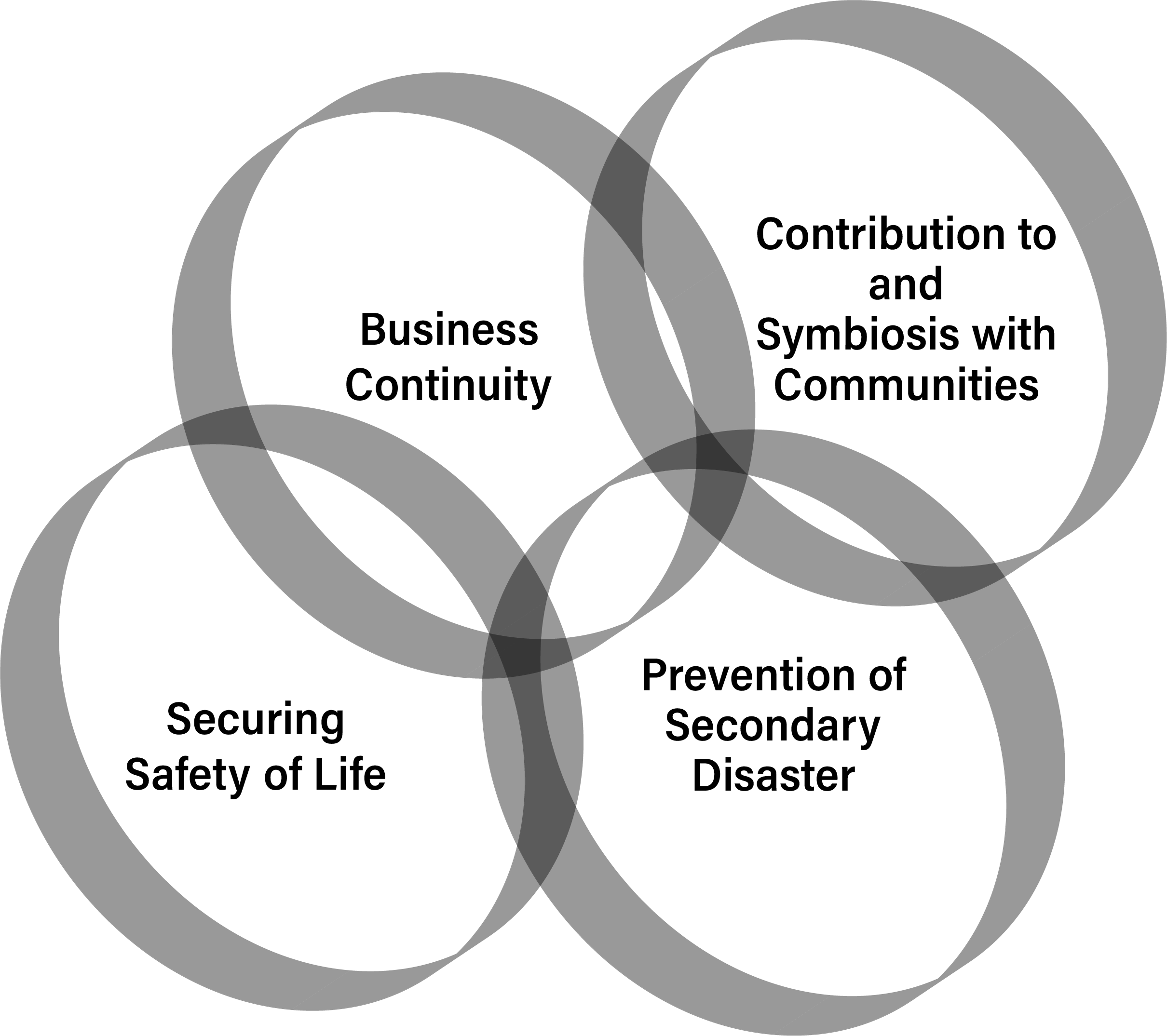

It goes without saying that the significance and importance of business continuity for road administrators lie in the rapid recovery of road functions on emergency transportation roads. In addition, it is also important to consider the following three points. Figure 3.2.1.2. shows the key points of the business continuity plan.

Figure 3.2.1.2. Key points for business continuity planning

Priority should be given to ensuring the safety of drivers on the road, customers evacuated to service areas, customers evacuated on the road, as well as employees who manage the road and their families. Confirming the safety of employees is a responsibility to ensure safety, but it is also important to understand the environment in which employees can work on recovery.

It is necessary to take all possible measures to prevent secondary disasters from the perspective of ensuring the safety of the neighborhood, such as increased damage to roads, secondary fires caused by road damage, and the collapse of nearby buildings and structures.

In the event of a disaster, it is necessary to work with citizens, government, and related organizations to restore the local environment and seek the earliest possible recovery of the local community.

It is important to periodically review and improve the formulation, maintenance, and updating of BCPs, securing of budgets and resources to achieve business continuity, implementation of proactive measures, education, and training to instill initiatives, inspections, and continuous improvement. Figure 3.2.1.3. shows the concept of the continual improvement of business continuity management.

Figure 3.2.1.3. Continuous improvement of business continuity management

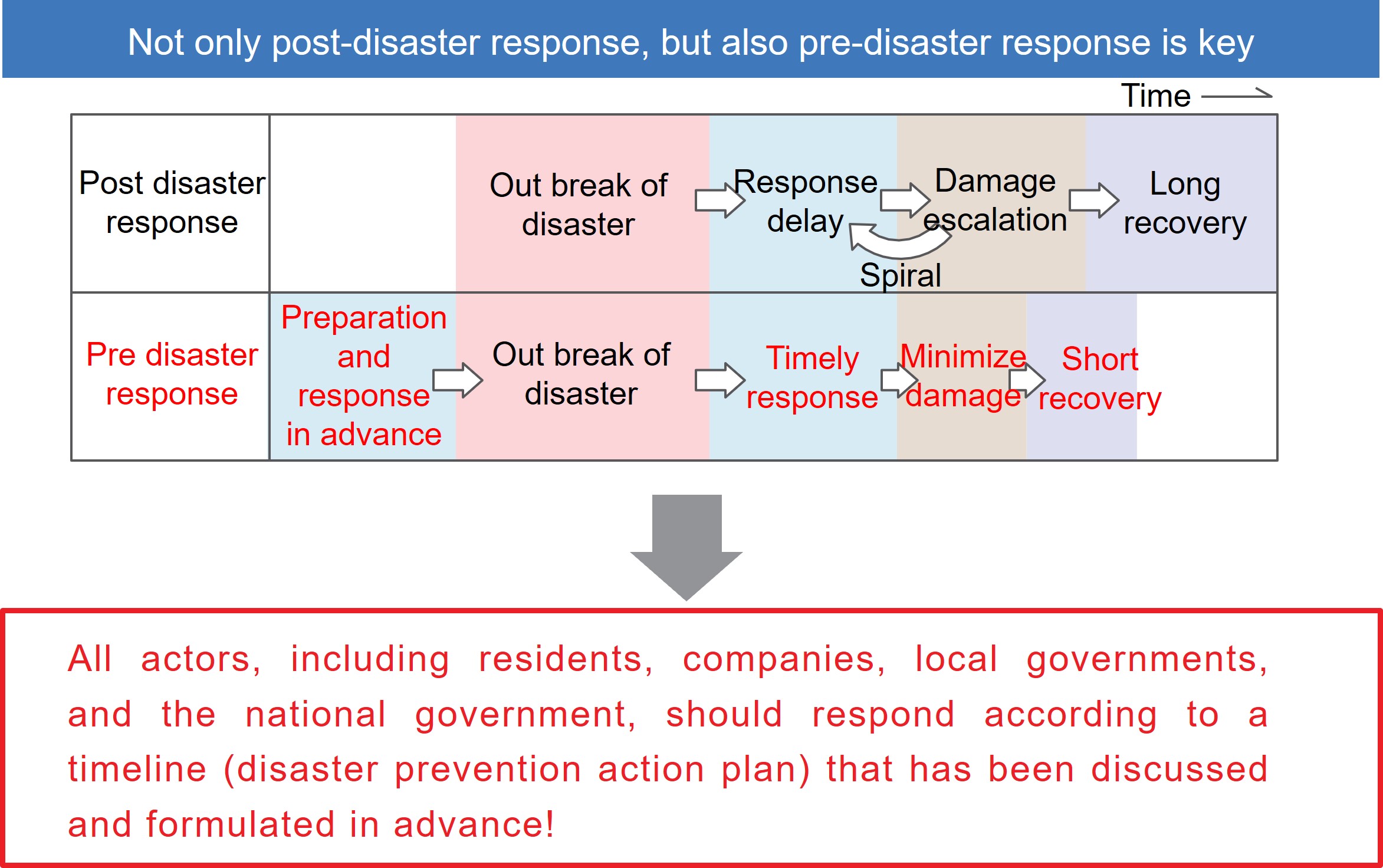

Record-breaking heavy rains and windstorms, as well as associated flooding, have occurred in recent years, especially in urban areas. For such risks where the damage can be foreseen to some extent in advance, it is important to develop disaster response actions along a timeline based on the assumption that the damage will occur. In the United States, Hurricane Sandy in 2012 caused a lot of damage in many areas, but New Jersey, New York, and other states responded based on a timeline plan and succeeded in reducing the damage 1, 2.

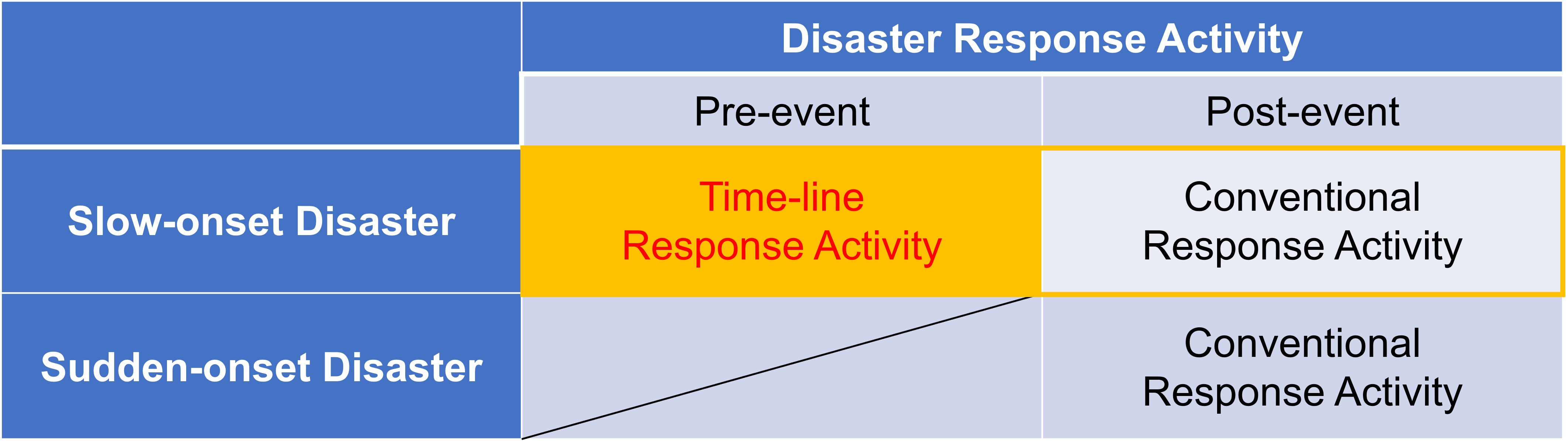

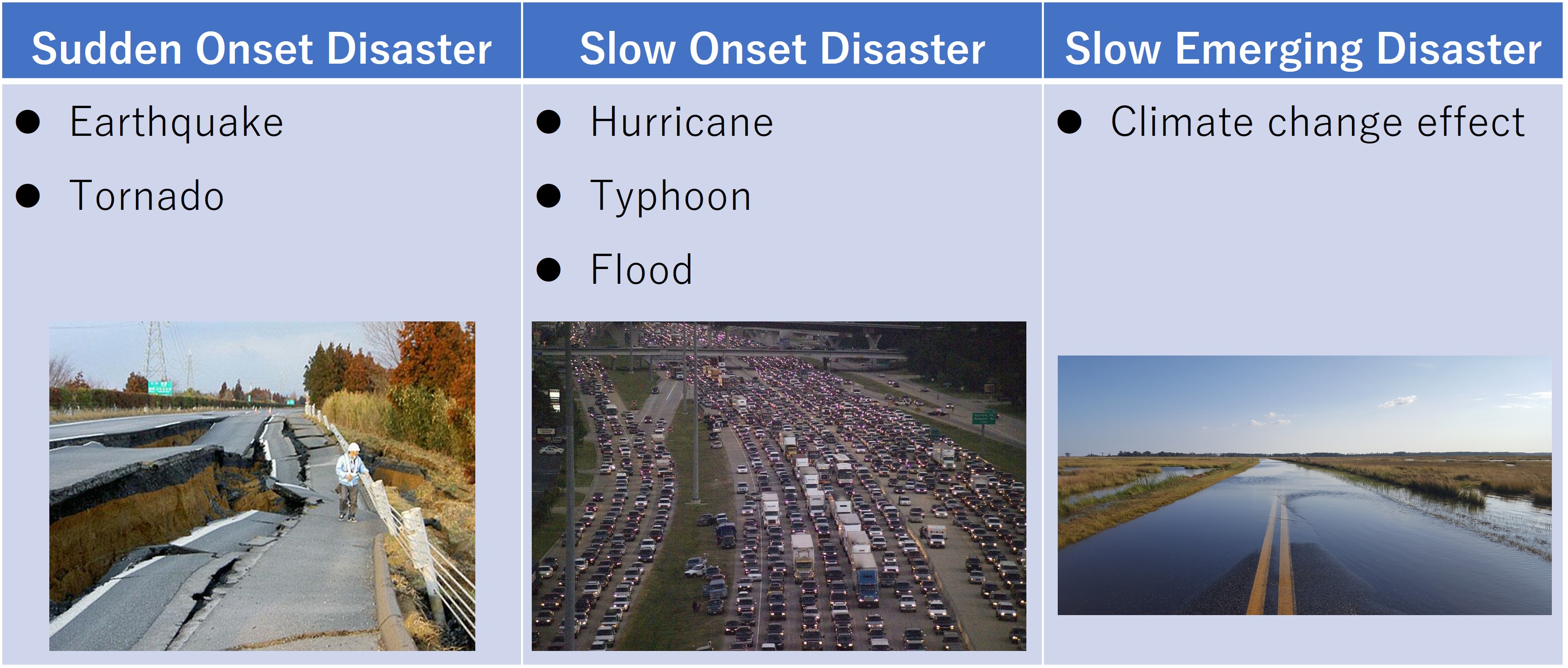

A timeline disaster response plan is a programmed plan of the countermeasures to be implemented in advance by relevant organizations in a time-line counted down from the outbreak of the disaster to deal with risks for which damage can be foreseen to some extent in advance. The purpose of this plan is to improve disaster response activities by preparing as much as possible before the outbreak of the disaster and reducing the burden of post-disaster response. The outline of the timeline plan is shown in Table 3.2.2.1, and the classification of disasters and the disasters for which the timeline plan will be effective are shown in Table 3.2.2.2. Although natural disasters are listed here, the timeline plan is also effective in dealing with pandemic cases such as influenza.

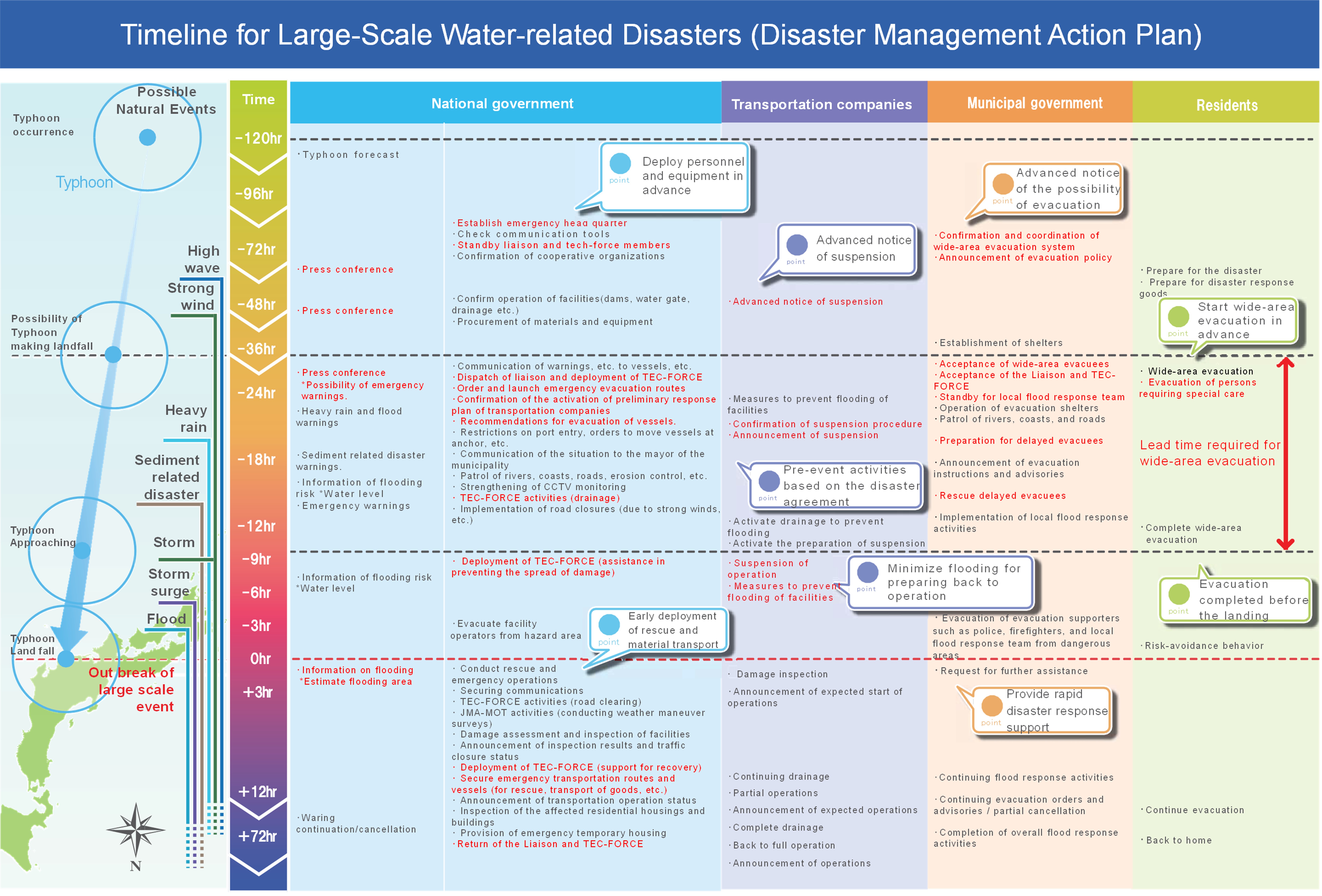

Large-scale water-related disasters such as storm surges and floods caused by large typhoons are disasters that can be predicted to some extent several days in advance. In response to such disasters, it is possible to minimize damage by the cooperation of the relevant organizations with each other, preparation of the response plans in advance based on the assumption that damage will occur, and proper implementation of those plans at the time of the disaster. The response plan should be developed based on the different scenarios: one is to prevent the damage and the other is to minimize the effect of the damage even though the damage will occur. In timeline planning, the time when a disaster outbreak is called "zero hour". The goal of the timeline plan is to complete the evacuation of not only the residents but also the administrative authorities, fire departments, and all other personnel who may be affected by the disaster by zero hour.

The timeline can be an effective method for the risks where the occurrence of damage can be foreseen to some extent in advance. On the other hand, it is difficult to use timelines for the risks such as sudden outbreak earthquakes, where the lead time between the appearance of the risk and the occurrence of damage is extremely short.

When Katrina made landfall in the southern United States in August 2005, it was a disaster of unprecedented scale, submerging most of the city of New Orleans when the levees broke. In particular, many victims were the elderly and the poor who could not evacuate by car, which pointed out the need for appropriate pre-disaster responses such as evacuation preparedness in response to an approaching hurricane. This experience has pointed out the importance of having a disaster preparedness plan in place in advance 3.

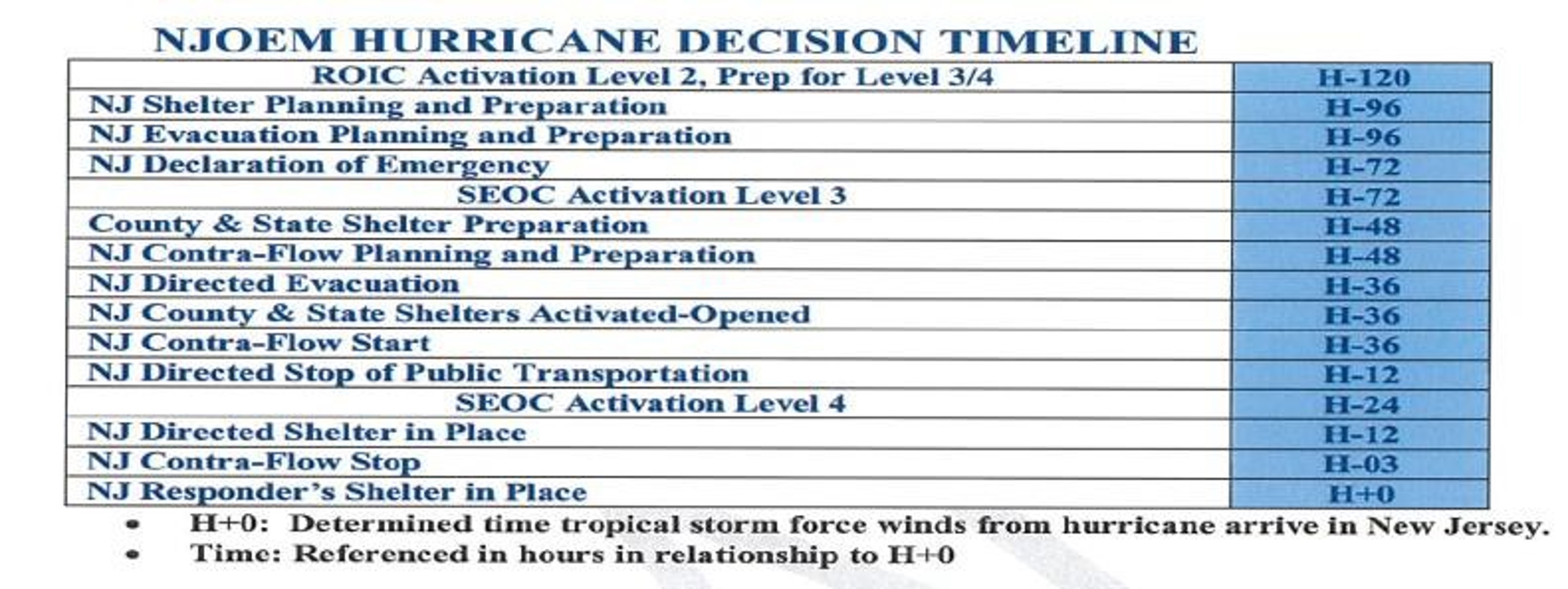

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy made landfall in North America, hitting major cities such as New York as shown in the damage photo of Figure 3.2.2.1. 4 Based on the lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina, the states of New York and New Jersey formulated disaster response programs based on scientific risk assessments in order for "pre-event response plan" and "post-event response plan," assuming that a hurricane of any scale could strike. It has been reported that the early response, including the suspension of subway and bus services and evacuation of residents according to the timeline as shown in Table 3.2.2.3 5, was successful in minimizing damage. There are also reports of active risk communication, in which top government officials call on residents and disaster management agencies to prepare for a disaster even before there is a possibility of a large-scale disaster 6.

Figure 3.2.2.1. Flooding caused by Hurricane Sandy

It is strongly recognized that there is no upper limit to disaster assumptions, and it is necessary to enhance preparedness to cope with the worst-case scenario. For this purpose, it is important to set two levels of risk and develop countermeasures as shown in Figure 3.2.2.2 7.

The first is the "prevention level”, which is the risk level at which measures are taken to prevent damage.

The second is the "response level," which is the risk level at which measures should be taken to minimize damage even if it occurs.

In response to these assumptions, the timeline disaster response plan defines the "when," "who," and "what" in strict timeline order in advance. When formulating a timeline disaster response plan, it is necessary to identify the parties involved, to divide the roles among them, and to calculate the timing of the implementation of the assigned roles, in order to plan for, for example, evacuation instructions to residents, road closures, and other disaster avoidance tasks. It is possible to mitigate damage by preparing, agreeing, sharing, and training on what should be done in the event of a disaster from the normal time among related parties. Figure 3.2.2.3 7 shows an example of the timeline for large scale water-related disasters.

In order to respond quickly and accurately, it is important not only to ensure thorough preparation in accordance with the action plan, but also to establish a basis for cooperation among the top management of related organizations, the unification of situational awareness, and problem-solving in the event of an unexpected incident.

This will have the following advantages

Figure 3.2.2.2. Importance of the pre-disaster response

Figure 3.2.2.3. Example of the timeline for large scale water-related disasters

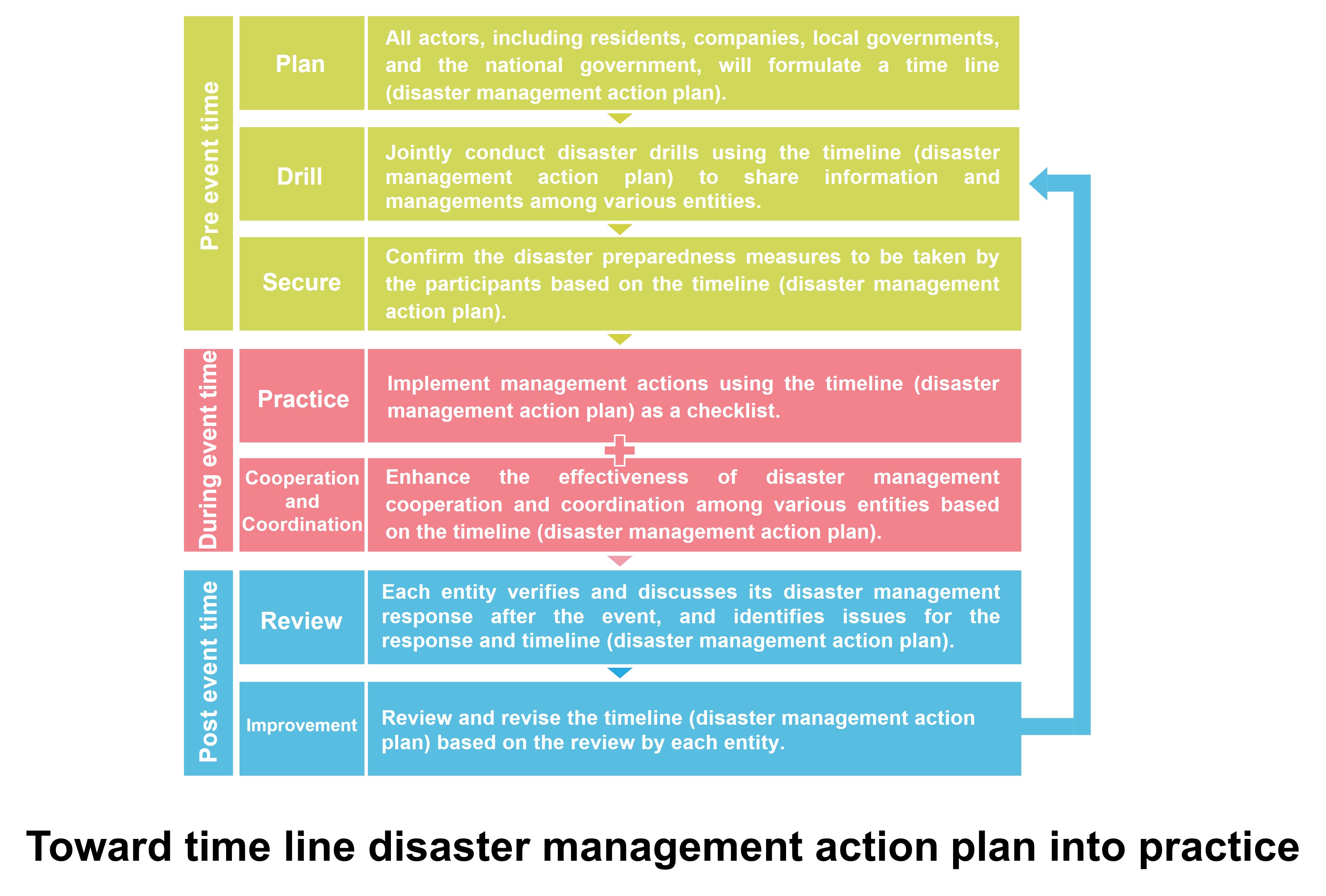

It is useful not only to have a disaster response plan in place but also to verify whether there are any problems with the plan and to constantly improve it. For this purpose, it is essential to review the plans for "when," "who," and "what" by conducting drills based on scenario events. Figure 3.2.2.4 7 shows the concept of continuous cycle for upgrading timeline disaster response plan.

Figure 3.2.2.4. Continuous cycle for upgrading timeline disaster response plan

The road network is one of the key factors in modern societies, both in economic and social terms. Road operation is primarily dependent on infrastructure. Risks to road network infrastructure and to associated control and information systems can occur in a variety of ways, either intentionally or accidentally as a result of various events. These emergency situations can be categorized into:

To optimize the preparedness, response and recovery of the road transport sector to emergency situations, cooperation with organizations at all levels (local, regional and national) and with operators of critical infrastructure is needed so as to ensure appropriate integration of these entities to emergency management.

This section includes a comparison study of Emergency Management Manuals and Business Continuity Plans for pre- and post-emergency principles, practices and actions related to road network in six countries – Australia, Canada (Québec), United States of America, Japan, Romania and New Zealand. Good practices for the different stages of the emergency management procedure are then summarized.

2. Comparison study of emergency management manuals and business continuity plans

Each country has their own detailed approach to emergency situations, however, they all follow a consistent high-level process based on three key functions.

This can be further broken down into a number of key phases as shown in Figure 3.2.3.

Figure 3.2.3. Key phases in emergency management

The following sections provide a summary of each countries emergency response processes in terms of pre- and post-emergency. This is followed by a summary of ‘best practice’ based on the existing processes and experience from the six countries reviewed as part of this report.

In New South Wales the emergency management best practice is based on the following principles:

In planning for a recovery, New South Wales continuously gather information about resources and equipment in order to establish logistics planning for the community at a local level. This means monitoring and intelligence gathering of information about supply chains, suitable locations, assets and resources. Evaluation and impact assessments carried out during and immediately after disaster event occurrence is especially valued in establishing the risk management plan for the area.

Building on this risk management plan there should also be a recovery plan identifying local recovery management structures, actions, roles and responsibilities, and be consistent with relevant State level plans. For an effective recovery these planning and managing arrangements must be accepted and understood by recovery agencies and the community. Emergency Management Committees at all levels are responsible for recovery planning.

These management arrangements call on several personnel depending on the need including:

Following a major emergency or natural disaster the best practice is for the initial impact assessment to be carried out within 24 hours. This assessment and recovery plan work together to set out the detailed action plan that will proceed.

The initial impact assessment defines the extent of damage, impact on the community and the potential need for a longer-term recovery process to take place. A delegated State Emergency Operations Controller (SEOCON) initiates this and the assessment is carried out with the assistance of combat agencies, functional areas and local government. The main duties of the combat agency will be the response operations, however New South Wales best practice emphasizes the importance of the early impact assessment info to be gathered and relayed to decide whether the damage can be managed locally in the short-term as part of the operational response, or requires more formal recovery arrangements.

Where the response operation and initial impact assessment has concluded that a more formal recovery arrangement is needed two things happen:

A State Emergency Recovery Controller (SERCON) consults with the SEOCON and a recovery Centre is established as a one-stop shop providing a single point of contact for information and assistance to disaster affected persons.

The function of the Recovery Committee is to strategically coordinate the recovery. Locally the committee is made up of Local Emergency Operations Controllers (LEOCONs) and the early meetings will be attended by the combat agency and the LEOCON to provide an overview of the situation. In the case of a regional recovery committee the effected Regional Emergency Operations Controller (REOCON) will meet to establish the composition of the Regional Committee.

The Canada Transport Agency has an Emergency Preparedness branch within their organization to:

In addition to this, in 1986 Canada and the United States re-formalized their history of emergency cooperation with the signing of The Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of the United States on Co-Operation in Comprehensive Civil Emergency Planning and Management. This agreement revolves around 10 principles of co-operation, which are to guide coordinated efforts in emergency preparedness.

The department plays a part in the following areas of emergency response: planning, exercise, training and response.

Same as with United States of America (USA), Canada deploys Transport Management Centres (TMC), which play an essential role in the response and recovery phase of an emergency. TMC participation in the National Response Framework and National Incident Management System (NRF and NIMS) frameworks are key to effective working relationships during recovery. Their roles extend to:

During an emergency or event, the TMC serves as a Transportation Department Operations Centre (TOC). It can be collocated with a state or county Emergency Operations Centre (EOC), which allows for close coordination between the Department of Transportation (DOT) and their counterparts in emergency response. It also allows the quick deployment of TMC resources for emergency response activities.

However, in an incident that spans multiple counties and even states, coordination among EOCs can become challenging. In at least one region, the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) is establishing procedures to aid communication and coordination among EOCs in an emergency.

The USA National framework for emergency response and recovery emphasizes that response to incidents should be handled at the lowest jurisdiction level capable for handling the works. The best practice model looks at all three phases of emergency response and recovery being:

The framework works to strengthen, organize and coordinate response actions across all levels based on the principle: “Mastery of these key tasks supports unity of effort, and thus improve our ability to save lives, protect property and the environment, and meet basic human needs”.

This section of the national framework is focused on capability building. In terms of the transportation sector best practice is divided into interagency communication and cooperation; emergency operations; equipment; ITS; mutual aid; threat notification, awareness, and information sharing; and policy.

In terms of coordination, the state Departments of Transportation (DOTs) and major transit agencies typically participate or take a lead role in the coordination efforts with state-level homeland security offices and state and local emergency management agencies (e.g. emergency and evacuation planning, multi-agency notification procedures, public information coordination). For regions encompassing several states Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO) take the lead role.

Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) practices differ between regions. Those identified as beneficial include:

Japan is very much exposed to natural disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis. Disaster risk reduction is covered in the budget of national and local governments. At the national level, the annual budget for disaster risk reduction is approximately $ 11 billion, which is about 1% of the total general-account budget expenditure (year 2010).

Cooperation and coordination among disaster response organizations are seen to be essential in emergency response and recovery. However, even in Japan, only highway companies or local road authorities that have suffered large-scale disaster actively worked on making such emergency agreements with other organizations. Japan has seen success on these collaboration agreements both planned and spontaneous and has based their best practice of emergency response and recovery as well as BCP on these case studies.

What stands out the most for Japan’s Best Practice for emergency response and recovery is their collaboration agreements that extend beyond emergency response type activities with frequent workshops and emergency drills. This makes implementation of the collaboration much smoother in an emergency as collaboration becomes business as usual.

Collaboration Agreement features:

Collaboration Activities:

Recovery measures are aimed at the early restoration of road services after the disaster. The best practice is to have had time-series response plans already planned out and preferably undergone drills. The targeted time of each action should be reflective of the priorities being rescue followed by provision of emergency escape routes and network restoration.

The responsibility for managing emergency situations belongs to different organizations depending on the type of road:

Permanent and Temporary Activity Operational Units are set up by the responsible organizations. These Activity Operational Units approve decisions during emergency situations relating to the road networks.

The Permanent Activity Operational Unit has specialized staff to manage risks. The size of the unit depends on the nature, frequency and severity of major risks.

Pre-emergency, the permanent activity operational unit is responsible for risk management:

It is a requirement that flood management plans are in place for those roads likely to be affected. These should cover protection, prevention and intervention. Plans for flood management must:

Intervention stocks are required close to the areas likely to be affected. These are to be maintained and remain available in case of an event.

Thresholds are to be set for intervention, and plans are followed if threshold reached:

Post-emergency, the permanent activity operational unit is responsible for:

Temporary Activity Operational Units are organized by the responsible organization and are only active during a time of emergency. This operational unit reports to the permanent operational unit.

The Temporary Activity Operational Unit is set up to provide information on:

The Civil Defense Emergency Management (CDEM) Act 2002 is intended to improve and promote the sustainable management of hazards. This relates to hazards that may impact on the social, economic, cultural, and environmental well-being and safety of the public, and property. The purpose of the act is to:

Each region is required to set up a CDEM group which brings together local authorities and emergency services in order to deliver the requirements of the CDEM.

Lifeline utilities are essential infrastructure services to the community. Identified lifeline utilities are required to have planning in place to enable the continuation of service in an emergency.

The CDEM 2002 Act defines two distinct aspects in terms of emergency readiness:

The incident response section in the specification for maintenance contracts sets out a minimal level of service for responding to incidents on the network. This ensures that maintenance contractors are prepared and ready to respond. The contractor must be prepared to:

Agencies are required to respond to emergency events by activating their own plans and coordinating their activities with other agencies:

Emergency Response Objectives include:

Transition from response to recovery:

Using the high-level approach to emergency response and recovery as established under section above (Preparedness, Response, Recovery) and the six examples of best practice emergency response and recovery of the road network in Australia, Canada (Quebec), United States of America, Romania and New Zealand, the following section provides a summary of key themes from those countries that define ‘best or practice’.

It is important that every Utility and Road Controlling Authority develops their own BCP for their organization. A key part of the process when developing a Business Continuity Plan is to undertake a risk analysis to establish what the key lifeline routes/utilities are so that an appropriate management plan can be developed for each of these and be communicated to other key organizations and the community.

It is also good practice during the planning phase to establish collaborations and supplier agreements to ensure resourcing, plant, response times, responsibilities and accountabilities and payment terms are agreed prior to any emergency event.

If an organization is both national and local/regional then development of a two part (or two separate) Business Continuity Plans is common practice. The detail provided within a local or regional plan will be different to what is required in a national plan.

Once individual Organizations have prepared their own Business Continuity Plans, it is common practice in a number of countries to establish some form of ‘Civil Defense Emergency Management Group (CDEG)’ or ‘Lifelines Group’. The purpose of these groups is to bring together Local Councils, Road Controlling Authorities and other Utility and lifeline Authorities so a coordinated national and local approach to emergency management planning is undertaken.

The CDEG groups can also form the single point of coordination and communication during an emergency, which is a critical function for the successful management and recovery following an event, although some countries establish a separate group to perform this function.

The CDEM groups focus should as a minimum cover:

A key component of being prepared for an event is ensuring regular training and emergency management simulations are undertaken with key response staff, both within individual organizations and across multiple organizations.

All countries with advanced procedures for emergency management and recovery have developed appropriate training programmes to ensure organizations are ready and well equipped to respond to an emergency.

A key aspect to all these training programmes is ensuring that an appropriate lessons-learnt process is undertaken after each training programme and implementation of business improvements is completed and audited.

Simulation drills and training should be real as possible, undertaken regularly and involve all people from workers on the road to senior management, wherever possible.

In the immediate aftermath of an emergency event there are some key processes that need to be undertaken that are consistent across all countries Business Continuity Plans. These are:

It is best practice for these plans to be “time series’ plans which change as the emergency develops. It is also common for new response plans to be developed during an event due to the developing and changing nature of an event. Ensuring appropriate resources are in place to develop and action the recovery plans is critical.

Communication with the road users advising them of road conditions is very important – Best Practice for this is discussed under section 3.2.2 above.

There were three key themes that came from the Business Continuity Plans regarding full recovery of the transport network following an emergency event. These are:

1 2003, Yoshiaki KAWATA, Crisis Management Theory: Towards a Safe and Secure Society, Disaster Prevention, Volume 4

1 2005 Cabinet office of Japan, Business Continuity Guidelines 1st ed. -Reducing the Impact of Disasters and Improving Responses to Disasters by Japanese Companies-, August

1 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/kokusai/disaster/america/

2 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/bousai/timeline/

3 2006 The White House, USA, The federal response to Hurricane Katrina: Lessons learned, February

4 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/kokusai/main/america/index.html

5 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flooding_on_FDR_Drive,_following_Hurricane_Sandy.jpg

6 http://www.nilim.go.jp/lab/beg/foreign/kokusai/hurricane-sandy-mid-gaiyou.pdf

7 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/shaseishin/kasenbunkakai/bunkakai/dai50kai/siryou12.pdf

8 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/shaseishin/kasenbunkakai/bunkakai/dai50kai/siryou12.pdf

9 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/shaseishin/kasenbunkakai/bunkakai/dai50kai/siryou12.pdf

1 2012. Ministry for Police and Emergency Services. New South Wales State Emergency Management Plan, December.

2 2006. U.S. Department of Transportation. Best Practices in Emergency Transportation Operations Preparedness and Response Results of the FHWA Workshop Series ANNOTATED, Federal Highway Administration. December.

3 2012. U.S. Department of Transportation. Roles of Transportation Management Centres in Emergency Operations Guidebook, Federal Highway Administration. October.

4 2003. Transportation Research Board. NCHRP Synthesis 318 Safe and Quick Clearance of Traffic Incidents, Washington D.C.

5 2012. World Road Association. Managing Operational Risk in Road Operations, PIARC Technical Committee C3 Report. A-5 Example 1 BCP for Highway operation- A case study for Hanshin Expressway-Japan, Managing Operational Risk in Road Organisation.

6 2010. Romanian National Company of Motorways and National Roads NORM Regarding the National Management System for Emergency Situationson Public Roads.

7 2006. N.Z. Ministry of Civil Defense and Emergency Management. The Guide to the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act, July 1 (Revised June 2009)

8 2005. N.Z. Bay of Plenty Civil Defence Emergency Management Group Plan, Civil Defense Publication 2005/01, ISSN 1175 8902. May.

1 https://hanshin-exp.co.jp/english/businessdomain/disaster/bcp.html

2 https://hanshin-exp.co.jp/english/businessdomain/disaster/bcp.html

1 2016 Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, transport, and tourism, First full-scale installation of emergency gates connecting river embankments and highways in the Chubu regio, January

2 2018 Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, transport, and tourism, Exercise of the Self-Defense Force vehicles transporting emergency materials and equipment at the emergency gate between the Meishin Expressway and the bank of the Kiso River, May

3 2018 Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, transport, and tourism, Exercise of the Self-Defense Force vehicles transporting emergency materials and equipment at the emergency gate between the Meishin Expressway and the bank of the Kiso River, May

1 2013 Tohoku regional development bureau, Tips for Disaster Management in the Initial Response Phase, March

2 http://infra-archive311.jp/en/s-kushinoha.html

3 http://infra-archive311.jp/en/s-kushinoha.html

4 https://www.ktr.mlit.go.jp/road/bousai/road_bousai00000011.html

5 2013 National Disaster Management Council, Cabinet office of japan, Damage Assumption and Countermeasures for a near field earthquake Directly Beneath the Tokyo Metropolitan Area (Final Report), December, http://www.bousai.go.jp/jishin/syuto/taisaku_wg/pdf/syuto_wg_siryo04.pdf

6 2013 National Disaster Management Council, Cabinet office of japan, Damage Assumption and Countermeasures for a near field earthquake Directly Beneath the Tokyo Metropolitan Area (Final Report), December, http://www.bousai.go.jp/jishin/syuto/taisaku_wg/pdf/syuto_wg_siryo04.pdf

7 2016 Chubu reginal development bureau, Chubu Version of Operation Tooth Comb, March

Disasters occur when hazards meet vulnerability. 1

Disasters occur when there are challenges in resilience to disasters due to lack of proper disaster management planning and appropriate risk management as compared to the severity of the hazard. Strengthening disaster resilience, hazard identification and assessment play a dual role in disaster management.

The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) defines a hazard as “a dangerous phenomenon, substance, human activity or condition that may cause loss of life, injury or other health impacts, property damage, loss of livelihoods and services, social and economic disruption, or environmental damage”. It also defines natural hazards are predominantly associated with natural processes and phenomena. 2

Multi-hazard means (1) the selection of multiple major hazards that the country faces, and (2) the specific contexts where hazardous events may occur simultaneously, cascadingly or cumulatively over time, and taking into account the potential interrelated effects.

Natural disaster hazards include floods, volcanoes, earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides and so on. Disaster management for natural disasters begins with the identification of natural disaster hazards and their appropriate assessment. In other words, it is important to identify the hazard and assess its risk level. Forecasting technology for all hazards has advanced, and in many cases, the results of damage prediction are compiled into hazard maps that are incorporated into disaster management.

In many cases, the hazard maps are organized in such a way that the risk of multiple hazards must also be considered. In many cases, overlapping hazard maps can also be used to study the possibility of multiple hazards.

Furthermore, in the case of landslides, the impact of the hazard itself may change due to changes in the ground conditions. In such a case, it is important to evaluate the impact of the hazard in real time by using monitoring technology.

In this section, hazard mapping and monitoring technologies are introduced.

A hazard map is a map that shows the expected disaster areas and the locations of evacuation sites, evacuation routes and other disaster prevention facilities for the purpose of mitigating damage caused by natural disasters and for disaster prevention measures. It is sometimes called a disaster prevention map, damage forecast map, estimated damage map, disaster avoidance map, or risk map. Hazard maps are created based on disaster prevention geographic information, such as the history of past disasters, evacuation sites, and evacuation routes, as well as topographical and geological features that contribute to the formation of the land and predisposition to disasters in the area. 1

By using hazard maps, residents can evacuate quickly and accurately in the event of a disaster and avoid areas where secondary disasters are expected to occur, which is very effective in reducing damage from disasters.

The general flow of Hazard Map development.

The process of developing a road hazard map can be divided into the steps indicated in Table 3.3.1.1 2 In general, maps of lower levels are created, and then analysis and evaluation are conducted. Level 1 and Level 2 belong to the "unstable area map". The quality of the hazard map is proportional to the quality of the identification of unstable locations.

| Step | Name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inventory map | A map showing the cause of the instability (topographical map, aerial photographic interpretation map, geological map, disaster history map, etc.) |

| 2 | Susceptibility map | A map showing the source of the instability (including a map showing the instability) |

| 3 | Hazard map | A map showing the area from the source to the impact area |

| 4 | Fragility map | A map showing the probability of occurrence of the above hazard (probability of source to impact area) in relation to the triggers. |

| 5 | Real time hazard map | A map of hazards that is updated and displayed sequentially, based on real-time data on rainfall and other triggers, and hazard assessment. |

| 6 | Risk map | A map showing the human and social economic risks of hazards. |

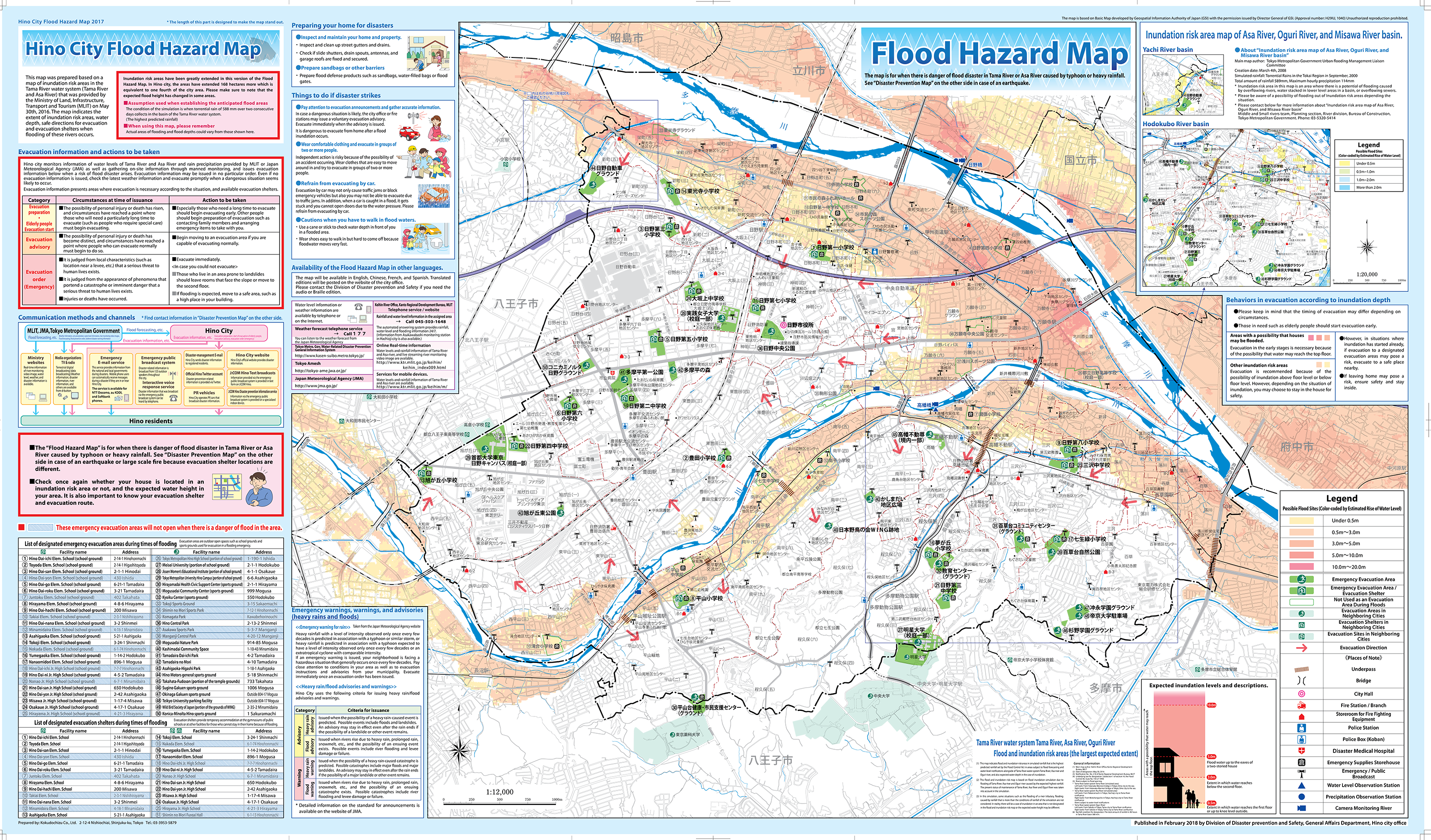

For the purpose of mitigating damage caused by floods by ensuring smooth and prompt evacuation or preventing flooding, flood hazard maps are published showing the estimated depth and duration of flooding for areas that are expected to be inundated if the river overflows due to the maximum possible rainfall. The areas that are expected to be inundated if the river overflows due to rainfall, which is the basis of the river flood prevention plan, and the expected depth of water in case of inundation are also published. These are generally referred to as flood hazard maps. 3 Figure 3.3.1.1 shows an example of the flood hazard map. 4

Figure 3.3.1.1 An example of flood hazard map

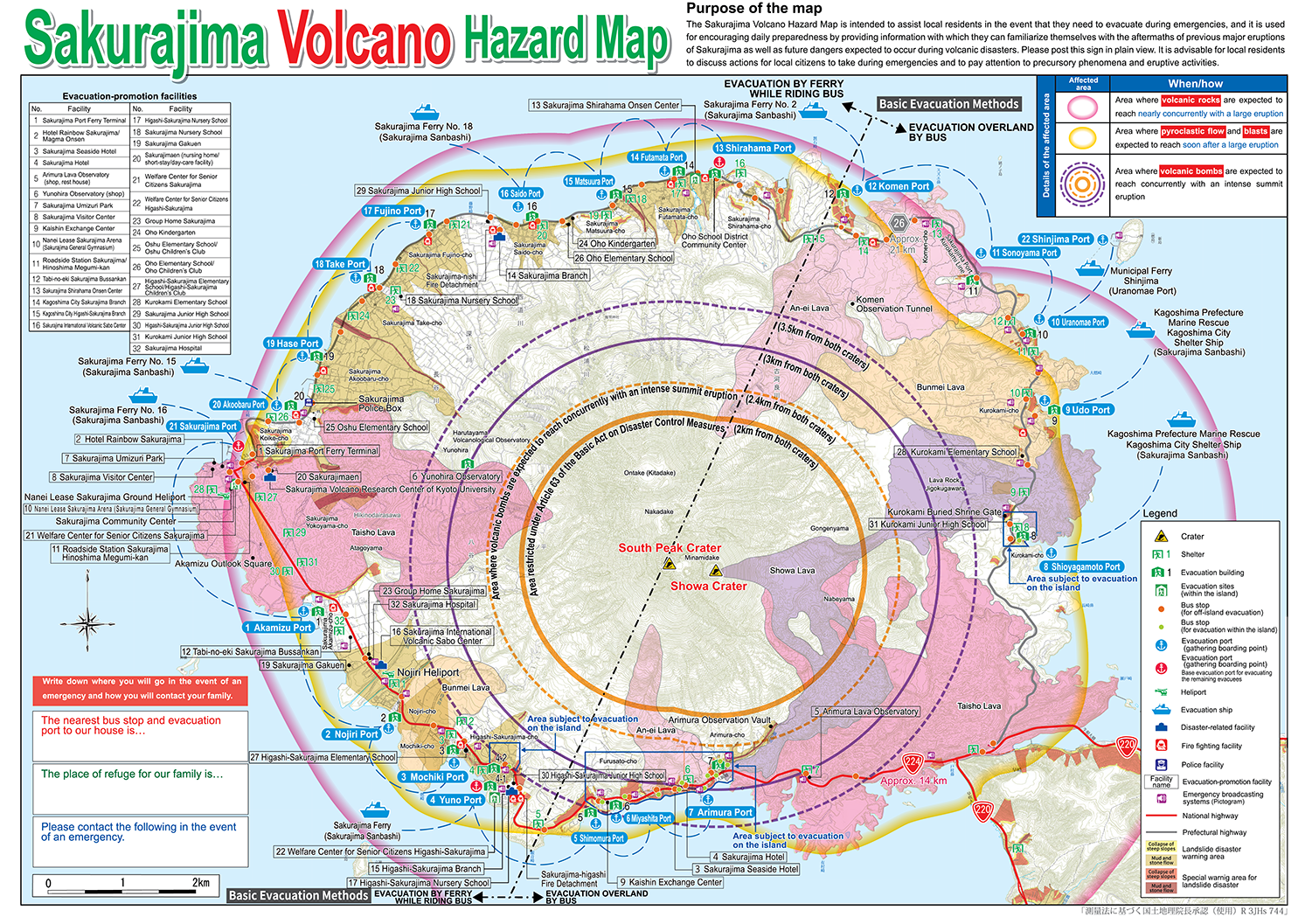

A volcanic hazard map is a map of the area that may be affected by volcanic hazards (large cinder cones, pyroclastic flows, snow-melting volcanic mudflows, etc.). The maps are used as basic data to study evacuation plans during normal times, and to study disaster prevention measures such as mountain entry restrictions, evacuation, and land use during eruptions. 5 Figure 3.3.1.2 shows an example of the volcanic hazard map.6

Figure 3.3.1.2. An example of Volcano hazard map

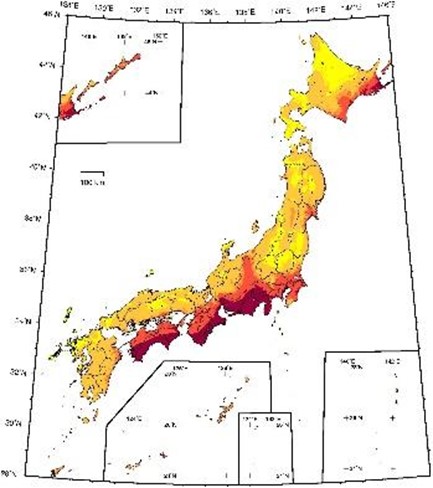

A seismic hazard map is a map that shows predicted information such as the level of tremors that may be caused by future earthquakes, the likelihood of strong tremors in each region within a certain period of time, and the extent of damage caused by earthquakes.

The probabilistic seismic motion prediction map is a map that shows the results of the evaluation of the possibility of strong shaking in each region in the future, taking into account the possibility of long-term occurrence of such earthquakes.

The "Earthquake Motion Prediction Map Specifying the Source Fault" shows how strong the shaking will be in the area to be evaluated when the earthquake occurs by assuming scenarios such as how the source fault will shift and move in response to a specific earthquake.

In addition, there are hazard maps that predict building damage by region and handle the risk of liquefaction of the ground.

Figure 3.3.1.3 shows an example of the seismic hazard map. 8

Figure 3.3.1.3. An example of earthquake hazard map

Exceedance probability within 30 years considering all earthquakes (JMA seismic intensity: 6 Lower or more; average case; period starting Jan. 2010)

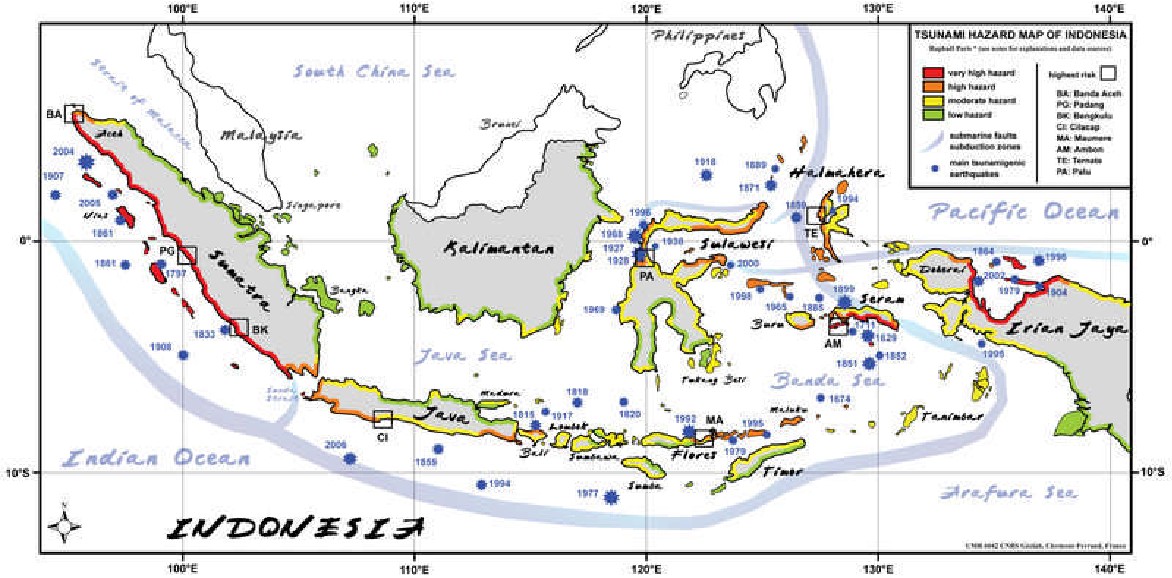

A tsunami and storm surge hazard map is a map that shows the anticipated damage area and the extent of the damage, as well as related disaster management information such as evacuation sites and routes, if necessary, for the purpose of considering evacuation of local residents and construction of facilities against tsunami and storm surge disasters. 9 Figure 3.3.1.4 shows an example of the tsunami hazard map. 10

Figure 3.3.1.4 An example of tsunami hazard map

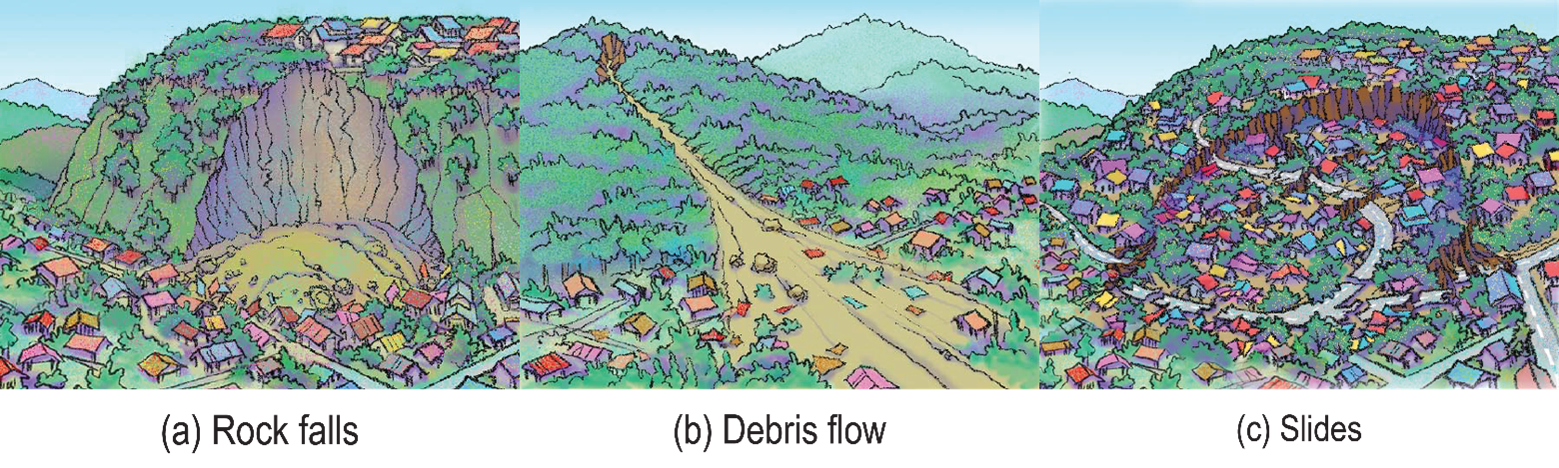

Geo-hazard is a phenomenon triggered by heavy rains or earthquakes that causes 1) mountains and cliffs to collapse, and 2) soil and rocks mixed with water to flow out of rivers.

A geo-hazard map is a tool to provide residents with information on the risk of sediment disasters and evacuation in the event of a disaster and is developed mainly for the purpose of helping residents evacuate in the event of a disaster.

Geo-hazard can be broadly classified into three types: Rock falls (collapse of steep slopes), Debris flows, and Slides as shown in Figure 3.3.1.5.

(a) Rock falls (collapses of steep slopes): Phenomena in which the resistance of soil materials is weakened by rain or earthquake and the slope collapses rapidly. When a Slope failure strikes a house, many people fail to escape, and the rate of death is high.

(b) Debris flows: Phenomena in which a portion of the soil, sand, and stones that make up a hillside or streambed is combined with water due to rain, etc., and swept downstream at high speed. The flow speed is 20 to 40 km/h and can destroy houses in a moment.

(c) Slide: Phenomena in which rock or soil mass on a slope slowly moves downward along the sliding surface due to the influence of groundwater or earthquake. It is a general phenomenon that covers a wide area and has a high potential to cause serious damage due to a large amount of moving mass.

Figure 3.3.1.5 Classification of geo-hazards

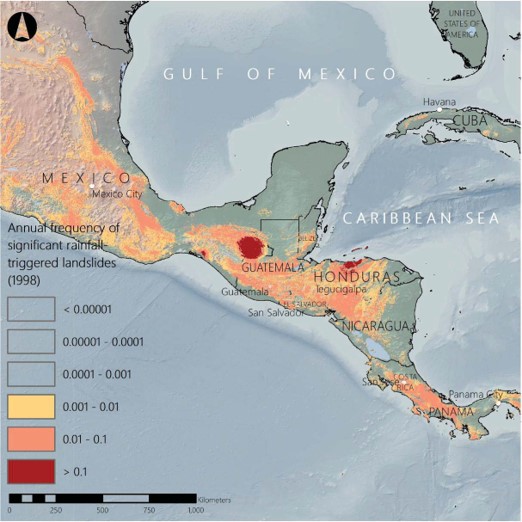

Figure 3.3.1.6 shows an example of the landslide hazard map. 12

Figure 3.3.1.6 An example of landslide hazard map

Monitoring is defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as "A continuing function that uses systematic collection of data on specified indicators to provide management and the main stakeholders of an ongoing development intervention with indications of the extent of progress and achievement of objectives and progress in the use of allocated funds” 1. The monitoring activity dealt with in this chapter is an activity to collect field data for evaluating the potential or hidden hazard risk.

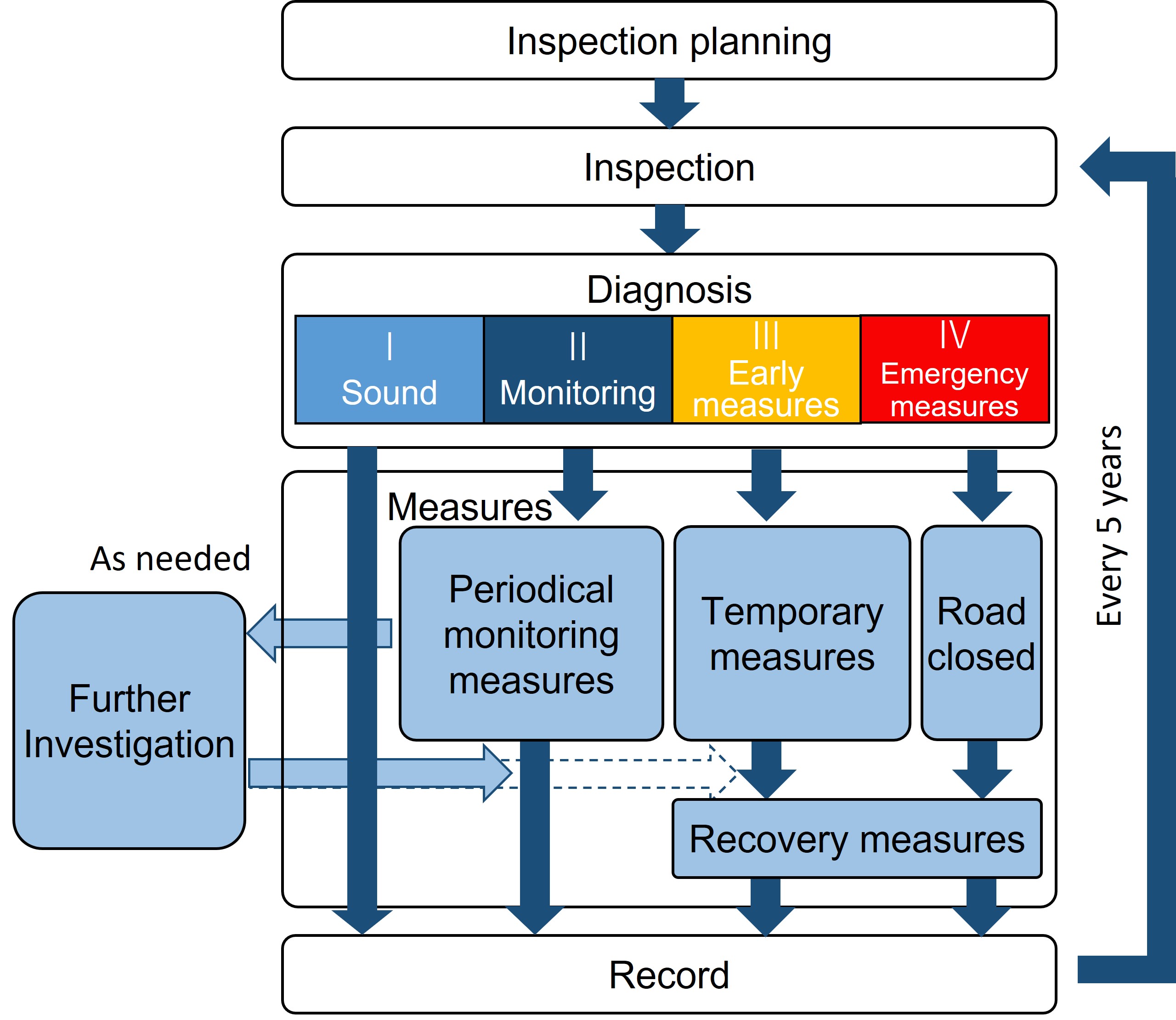

When disasters are organized with a focus on the timeline of their occurrence mechanism, some events are recognized as having a relatively long time from the precursor or initial event to the occurrence of the disaster. In the case of earthquakes and typhoons, the time from the occurrence of the event to the occurrence of the disaster is generally short. For such events, preparedness activities are focused relatively on mitigating the disaster by providing early warning information. On the other hand, in the case of a slope disaster, where there is some time from the precursor or initial event to the onset of the disaster, although there are exceptions, preparedness activities are focused on mitigating the disaster by detecting the precursor or initial event, strengthening monitoring of the precursor or initial event, and determining countermeasures against the initial event based on the results of the monitoring. It is also important for road administrators to maintain road functions as much as possible for economic activities while giving top priority to ensuring the safety of road users. Thus, monitoring activities are one of the most important preparatory activities in disaster management to determine the necessity of prior road closure or appropriate slope improvement and its timing by confirming the development of the initial event and its trend. Figure 3.3.2.1 shows an example of a road slope disaster. 2

Figure 3.3.2.1 Road slope failure (2010 Makinohara slope failure)

Figure 3.3.2.2 Maintenance management flow for slope structures

Figure 3.3.2.2 3 shows the management flow for slope disasters. Many inspections, monitoring, and countermeasure activities, as well as their overall management activities, are conducted to prevent or mitigate slope hazards. Since the mechanism of slope disasters is generally complex, it is important from the viewpoint of safety and efficiency to hand over from general maintenance activities to maintenance activities by specialists. Patrols and inspections are responsible for the detection of precursor events and initial events. However, patrollers and inspectors do not have specialized knowledge and training on slopes, and it is difficult for them to judge the influence of precursors and initial events on the progression to disaster occurrence. Therefore, it is necessary to shift to monitoring activities by experts to realize safe and efficient maintenance management.

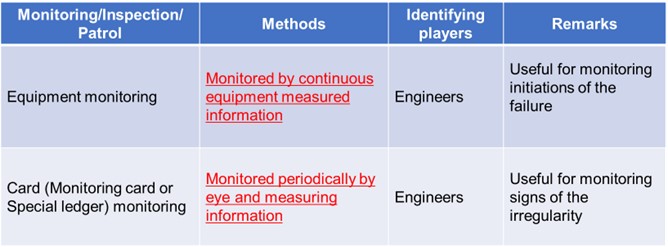

Monitoring can be classified into two categories: "chart inspection" (ledger inspection), in which data is collected periodically by visual inspection and measurement by expert inspectors and evaluated by expert engineers, and "monitoring" in a narrower sense, in which data is collected continuously using instruments to obtain more detailed data and evaluated by expert engineers. In Japan, especially in response to slope disasters, "chart inspection" is often conducted at the precursor stage, and if necessary, "monitoring" in the narrow sense is strengthened and "slope stability measures" are implemented. Thus, it is essential to utilize monitoring with different characteristics to ensure the safety of road users and to conduct efficient disaster management.

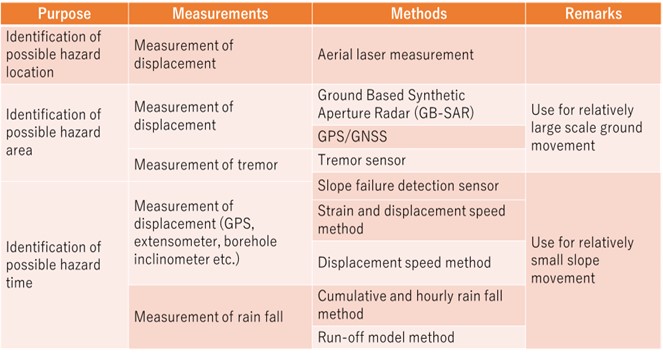

In the countermeasures against slope hazards, it is important to predict when, where, and on what scale, a slope disaster will occur. Table 3.3.2.1 4 shows a list of techniques for predicting when, where, and on what scale a slope disaster will occur.

For hazard prediction of "where" and "at what scale" road slopes will occur, satellite imagery, aerial surveying, and seismic observation have been used to identify large-scale possible hazard areas. However, due to the existence of a large number of road slopes in a wide area, the current situation relies on the detection of "anomalies" by road patrollers and regular inspectors. It is impossible to predict "when" a disaster will occur on a road slope with current technology. Therefore, structural measures (reinforcement, repair, etc.) are being taken to prevent the occurrence of disasters, and non-structural measures (road closures, etc.) are also being monitored to determine the necessity of such measures. For non-structural measures (road closures), "Early Warning Information" is issued based on rainfall monitoring information. This will be dealt with in the "Early Warning Information" section. As shown in Table 3.3.2.2, this chapter describes the "monitoring" that is conducted to obtain decision-making materials for structural measures.

In order to evaluate the stability of the slope and to determine the timing of the implementation of stability improvement measures, monitoring is divided into two types: continuous measurement monitoring using equipment, and chart inspection conducted by engineers using periodic visual inspection and simple measurements.

In continuous monitoring, the displacement rate (difference in displacement in hours or days) is calculated from the amount of displacement and strain obtained from extensometers, GPS, and in-hole inclinometers, and when the displacement rate exceeds the threshold value, stability improvement measures are carried out or the road is closed. Since the displacement rate that leads to slope failure varies depending on the size, slope, and material properties of the slope, the control threshold is set based on the characteristics of the individual slope based on laboratory tests and numerical analysis. However, due to the technical difficulty in predicting slope failure, the threshold values are often set based on the values proposed by researchers. For example, in the case of the threshold value for the extensometer, when the displacement rate reaches 2 mm to 4 mm/hour or more, the slope is judged to be close to collapse, and evacuation or road closure is often carried out. 4

In the case of GPS, when high measurement accuracy is required for engineering interpretation, such as slope failure and landslide, objective judgment can be made by statistically processing the time series data using the static method. Although it depends on the calculation environment and the installation method, it has become possible to detect sudden small displacements of about 2 to 3 mm by time-series statistical analysis.

In remote sensing, a method has been proposed to classify and process satellite data, to create ground thematic maps, and to create hazard prediction images through quantitative analysis based on these data.

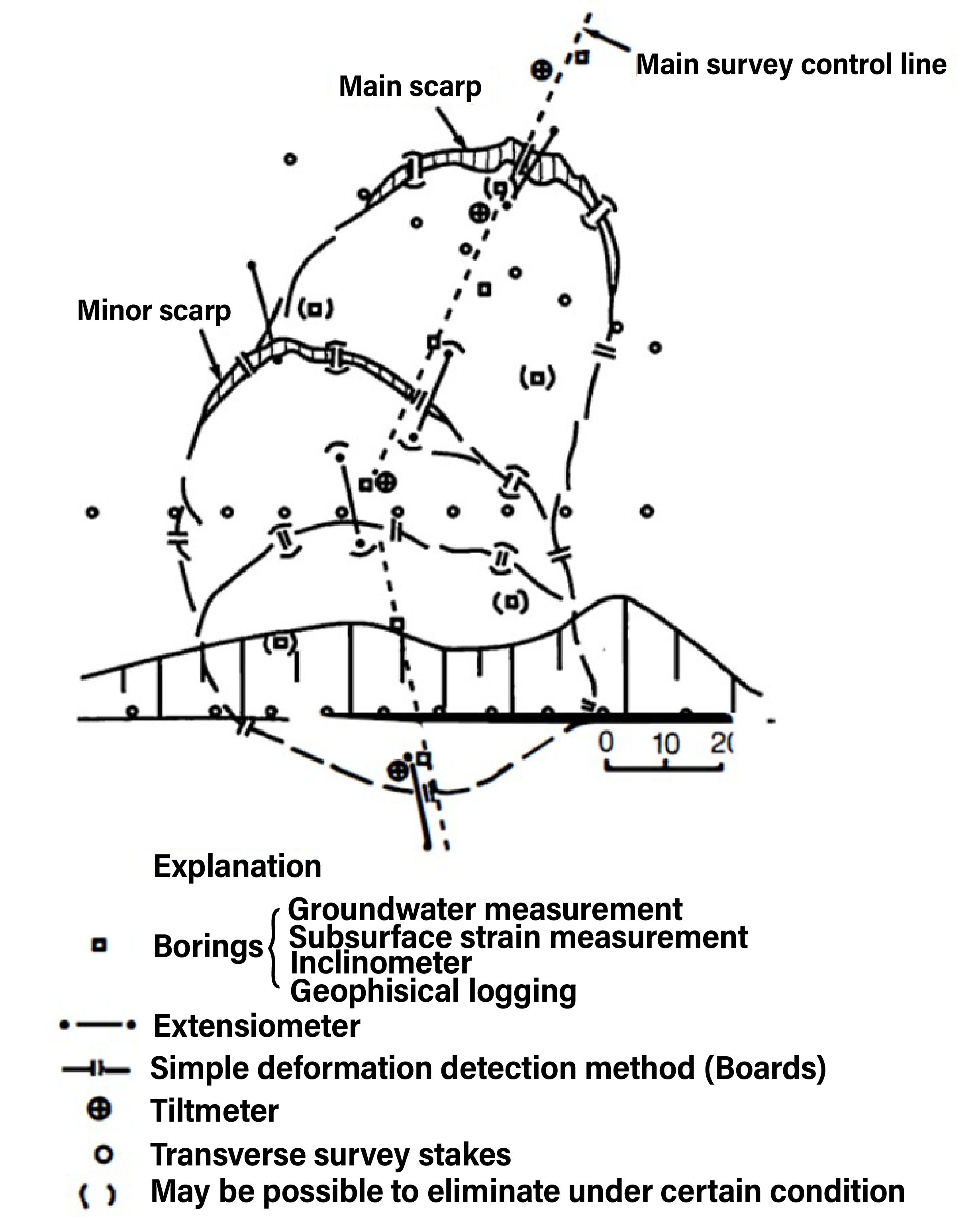

The investigation of surface deformation is conducted to define the boundaries of the landslide, size, level of activity and directions of the movement, and to determine individual moving blocks of the main slide. The presence of scarps and transverse cracks are useful for determining whether the potential for future activity exists.

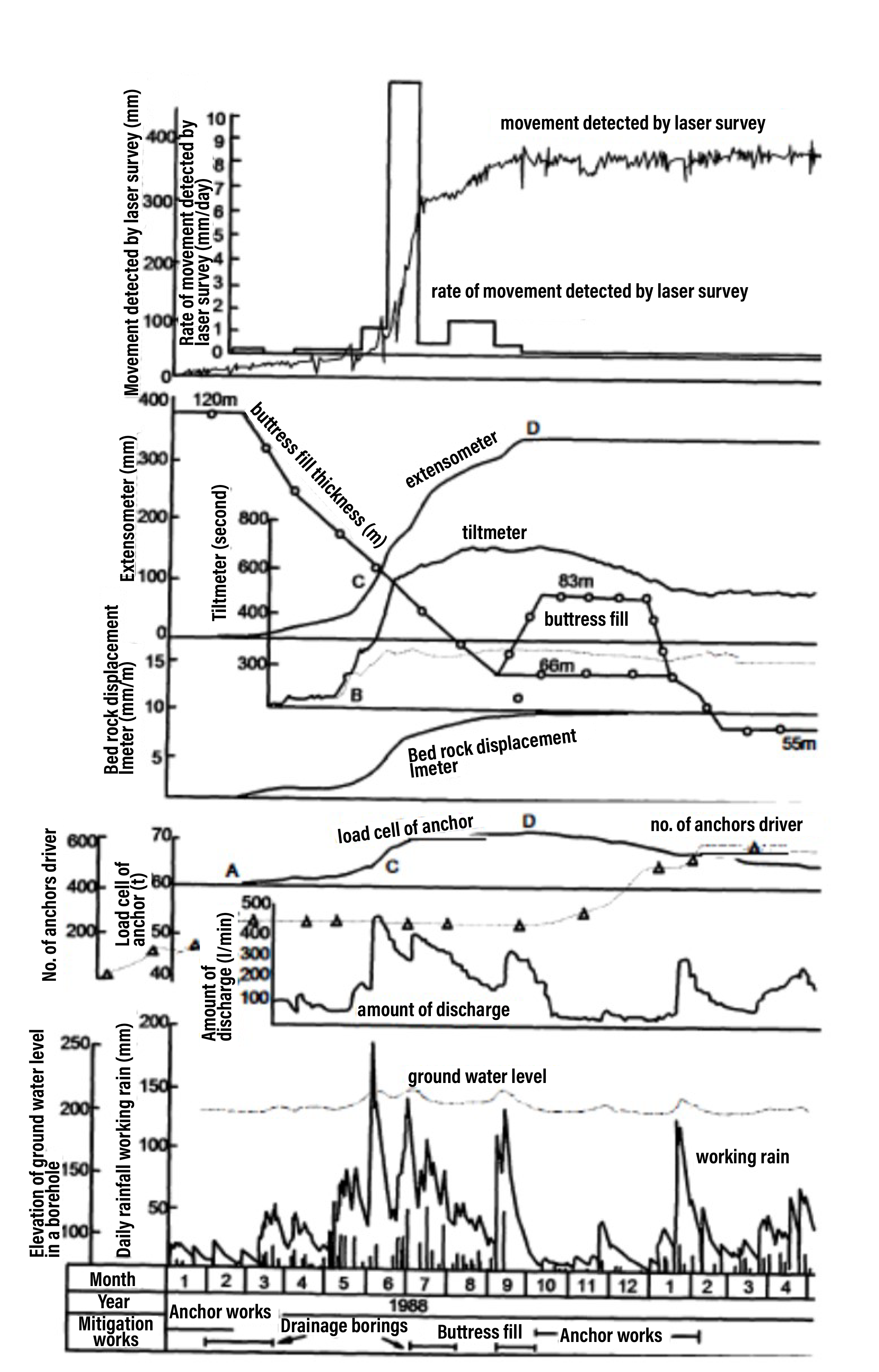

Examples of equipment used for the surface deformation investigation include extensometers, ground tiltmeters, movement determination by survey methods including transverse survey, grid survey, laser survey from the opposite bank, movement determination by aerial photographs, and GPS (Figure 3.3.2.3).

Figure 3.3.2.3. Example of equipment

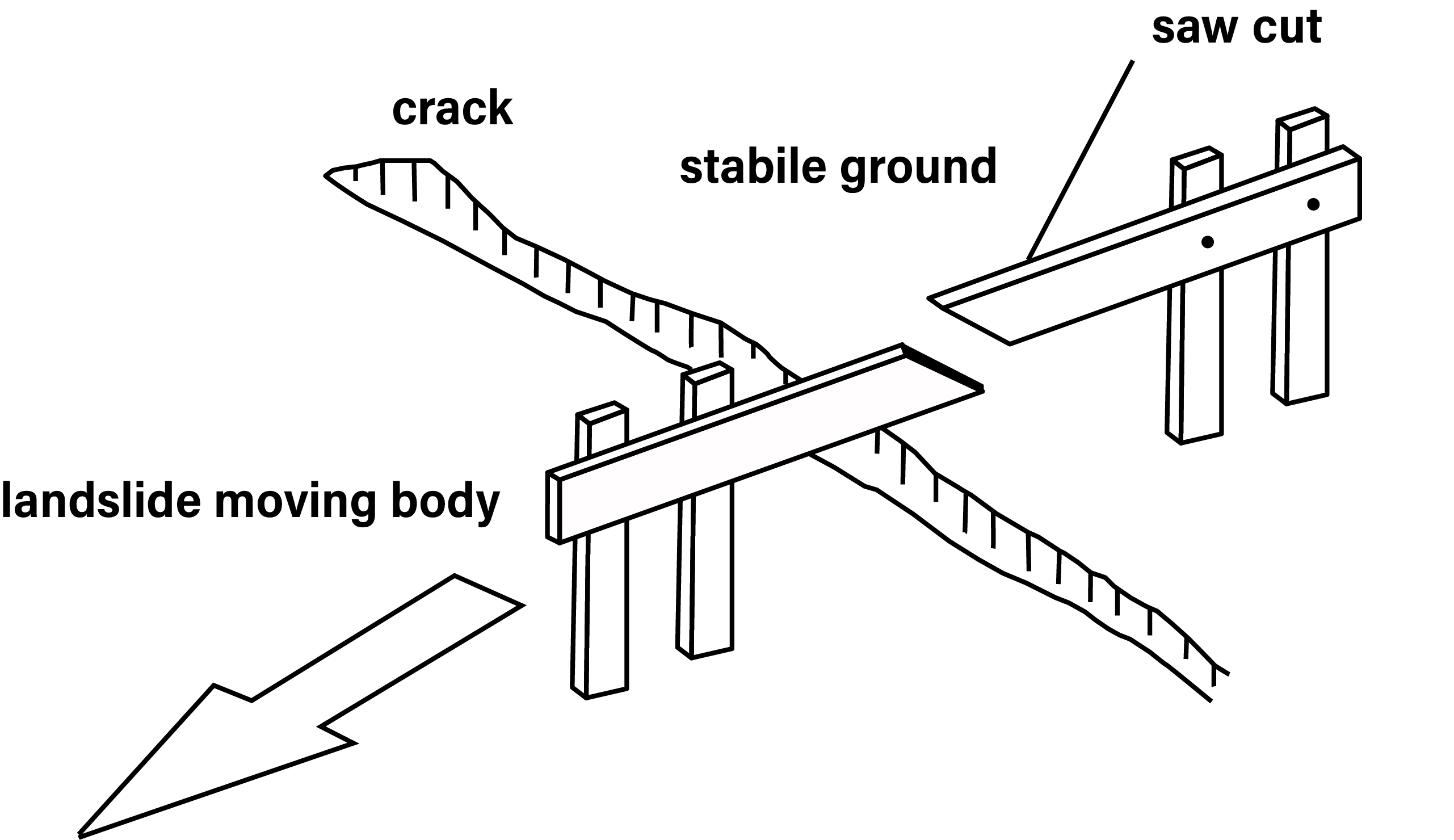

One of the simplest methods to determine landslide movement is to drive stakes across a tension crack along the direction of slide movement (Figure 3.3.2.4). Then attach a horizontal board to the stakes, and saw through the board. Any movement across the tension crack can be determined by measuring the displacement of the space created by cutting the board.

Figure 3.3.2.4. Simple deformation detection method (Broads)

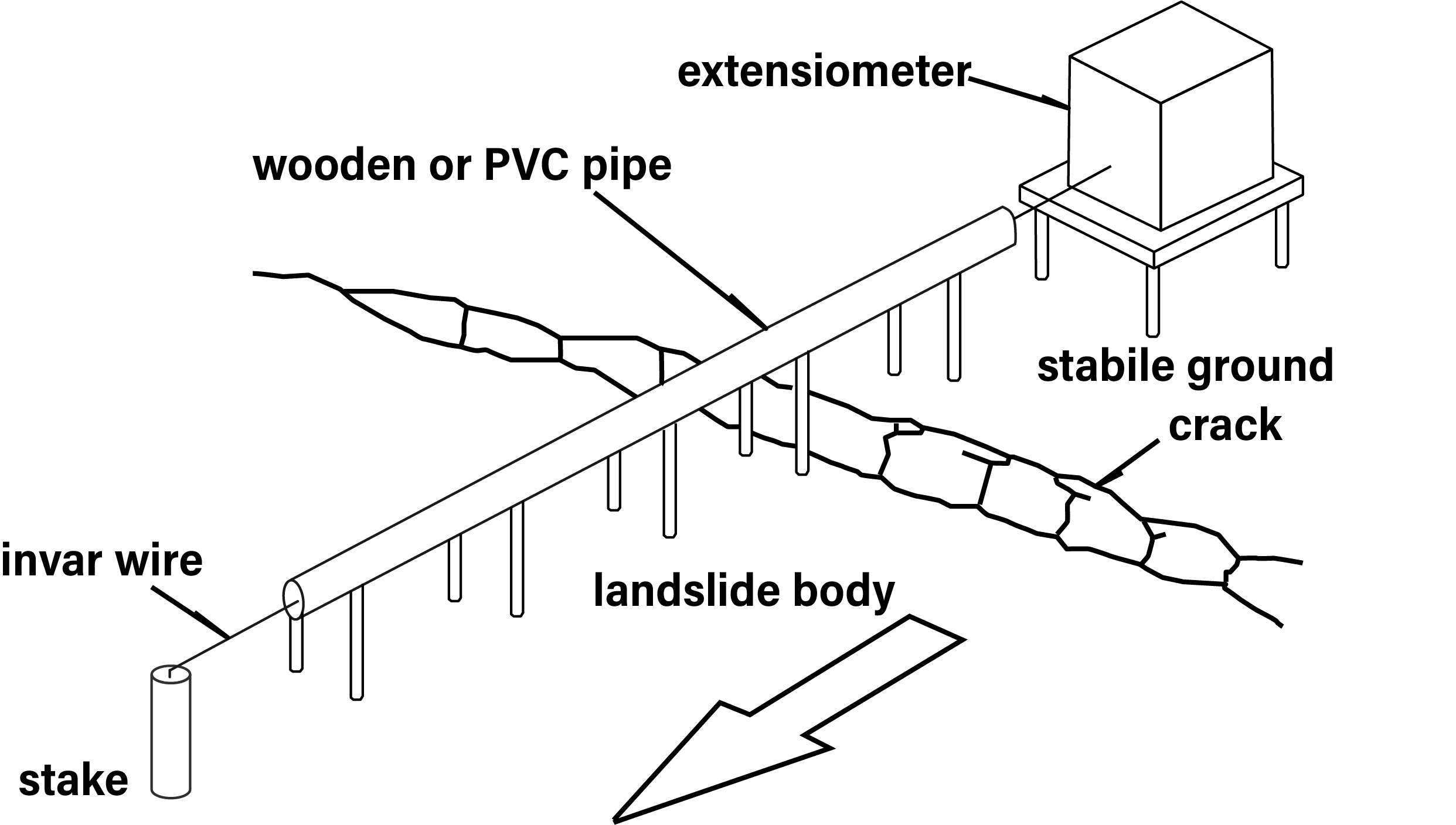

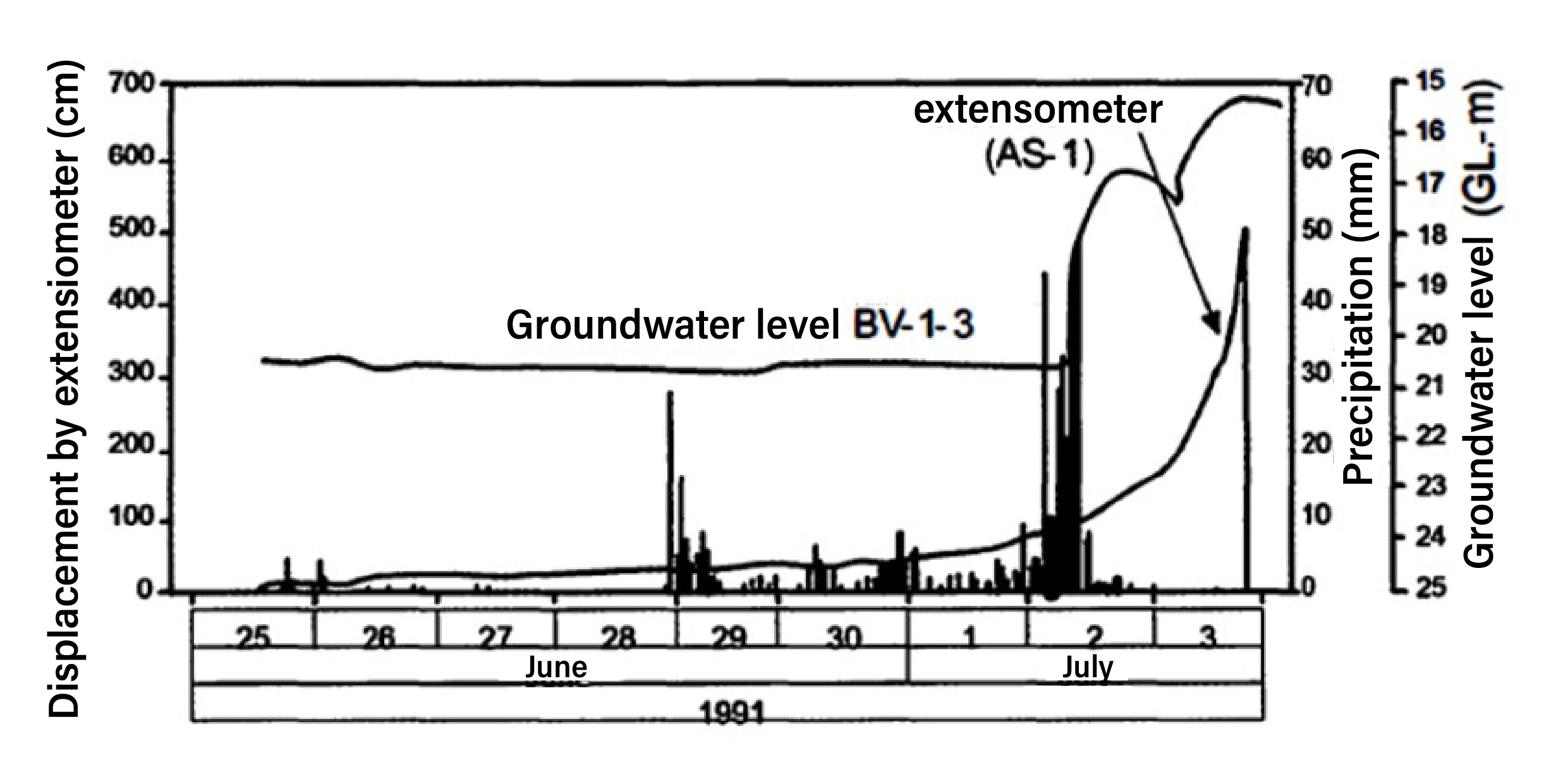

The extensometer is used to measure the amount of relative displacement between two points which are set on a moving and unmoving ground. The extensometers are generally installed across the main scarp, at transverse cracks and transverse ridges near the toe or front portion of the slide and parallel to the suspected slide direction (Figure 3.3.2.5). Measurements should be accurate to within 0.2 mm, and the magnitude of the movement and daily rainfall data should be recorded to establish the relationship between the measurable movement and the precipitation rate (Figure 3.3.2.6).

Figure 3.3.2.5. Simplified diagram for extensometer installation

Figure 3.3.2.6. Example of measurements by extensometer

A control point is established across from a suspected sliding area on stable ground, and survey stakes are positioned within the slide. Laser survey is most effective where landslides are very active and the movement is large. Recently, a non-prism optical distance meter has been developed which does not require a specific target, and is used for monitoring on very steep slopes.

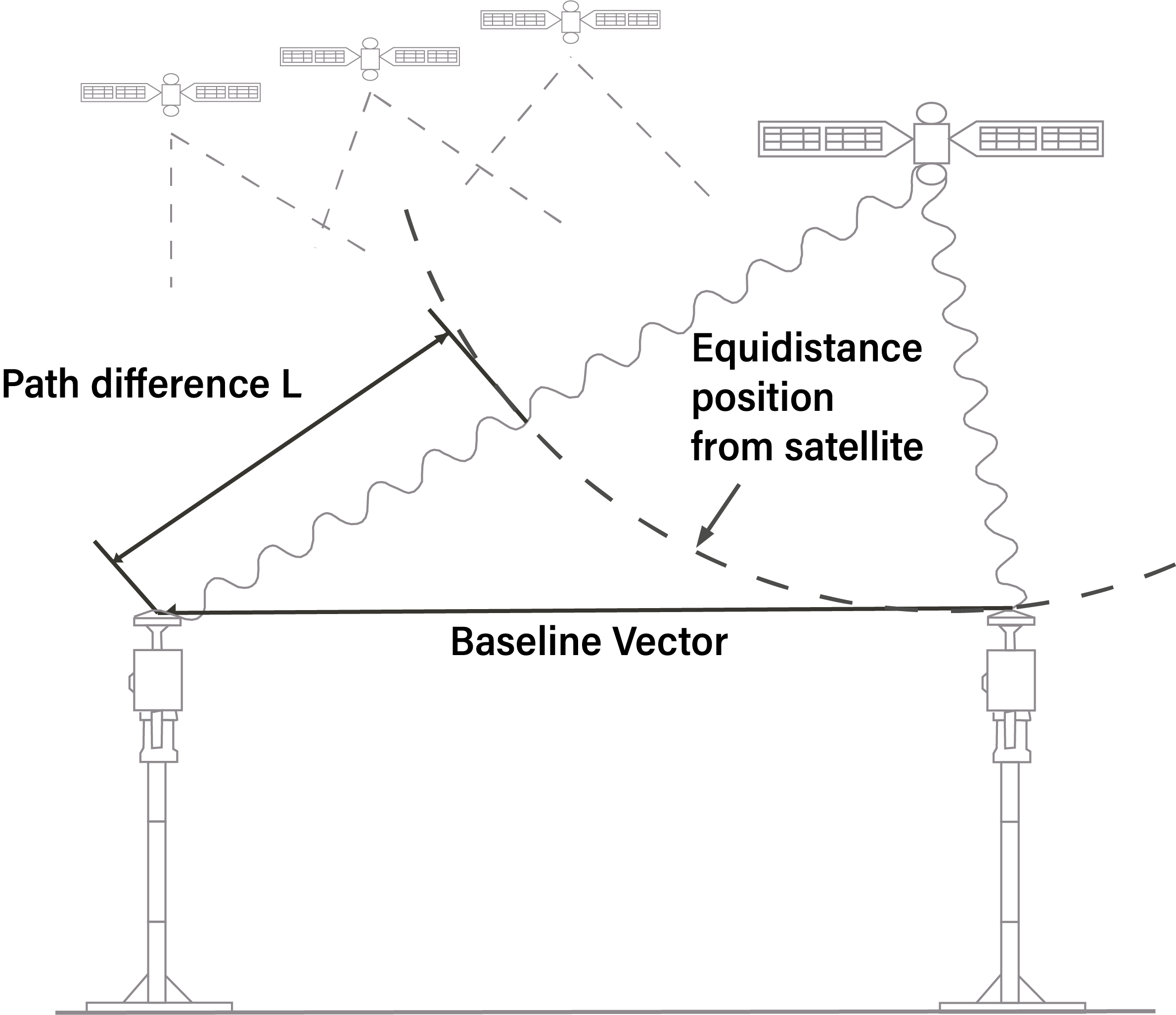

In recent years, GPS has been applied in landslide measurement to obtain three-dimensional positions of a landslide (Figure 3.3.2.7). It is also effective in identifying the moving direction and distances of a landslide.

Figure 3.3.2.7. A conceptual rendering of differential GPS

The ground tiltmeter is useful for determining the deformation at the head and toe and sometimes along the flanks of the landslide, or to assess the possibility of future deformation. A "level type" tiltmeter is most conventional.

Recently, slope deformation detection systems using fiber optics have been tried. This system adopts the property of reduction in the optic medium within the fiber optics as it bends. It is possible to record the amount of deformation as well as the location of the deformation.

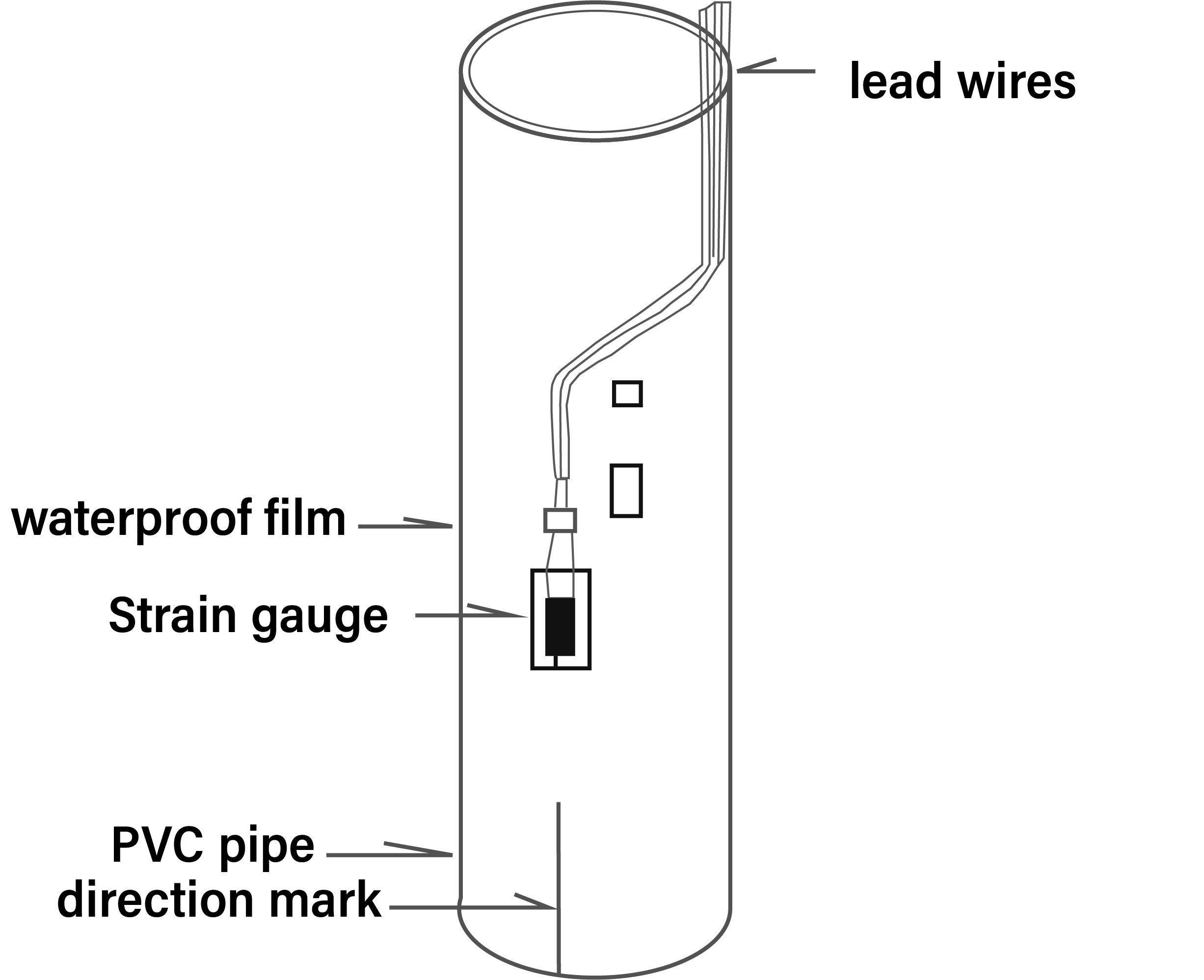

In order to identify the depth of slip surface for actively moving landslides, differences in velocities and moving patterns utilized along the slip surface are determined. Depending on the requirements for survey accuracy and magnitude of displacement, the appropriate instrumentation shall be selected from the following representative instruments: 1. Pipe strain gauge; and 2. Inclinometer.

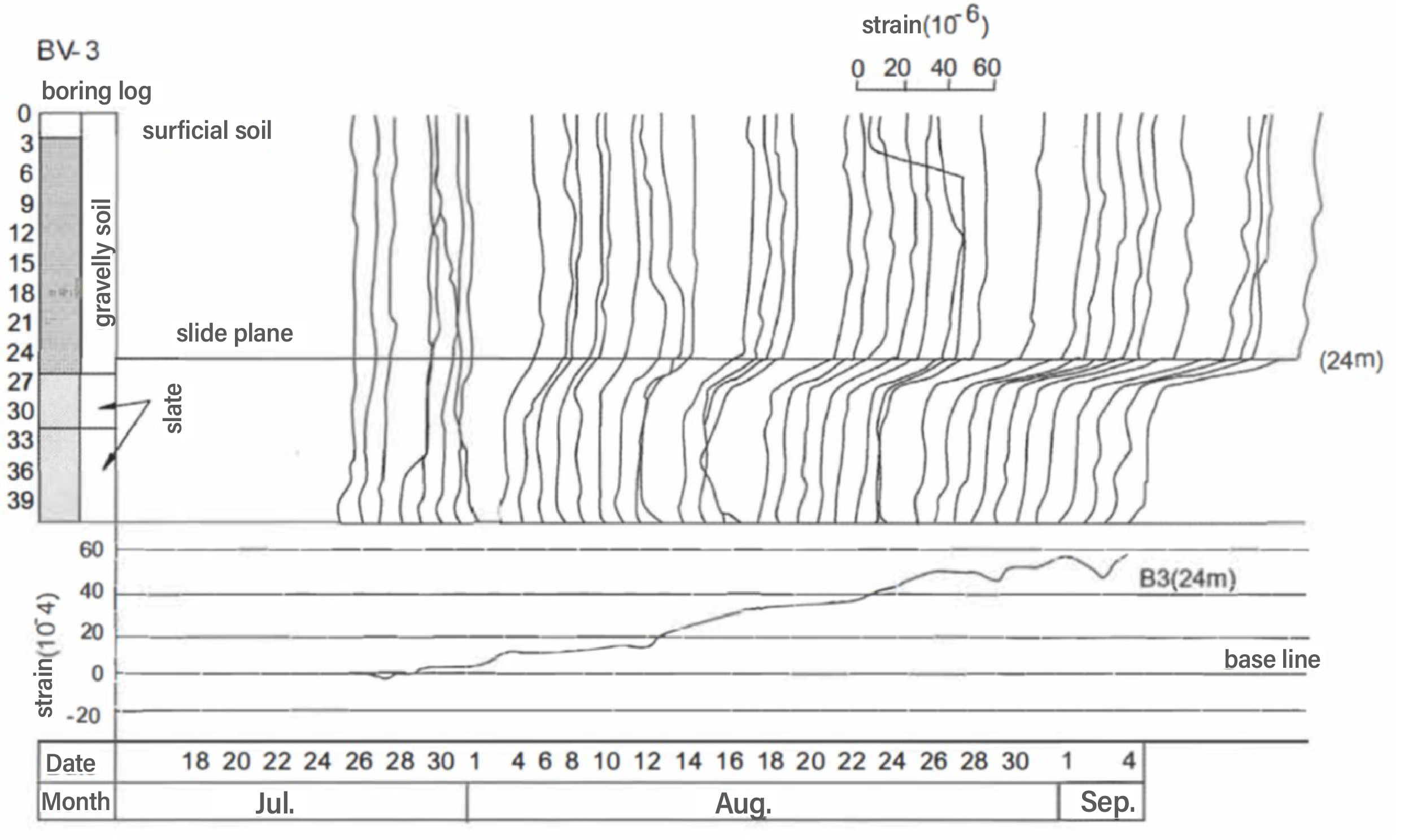

PVC pipes with strain gauges are inserted into the boreholes, and the movement is detected by the change in the strain as the PVC pipe bends (Figure 3.3.2.8, and 3.3.2.9). The accuracy of detection increases as the intervals of the gauge narrows. Some lowest strain gauges must be anchored into the bedrock below the slip surface so that data from within the intact formation can be obtained.

Figure 3.3.2.8. Pipe strain gauge system

Figure 3.3.2.9 Example of measurement by pipe strain gauge

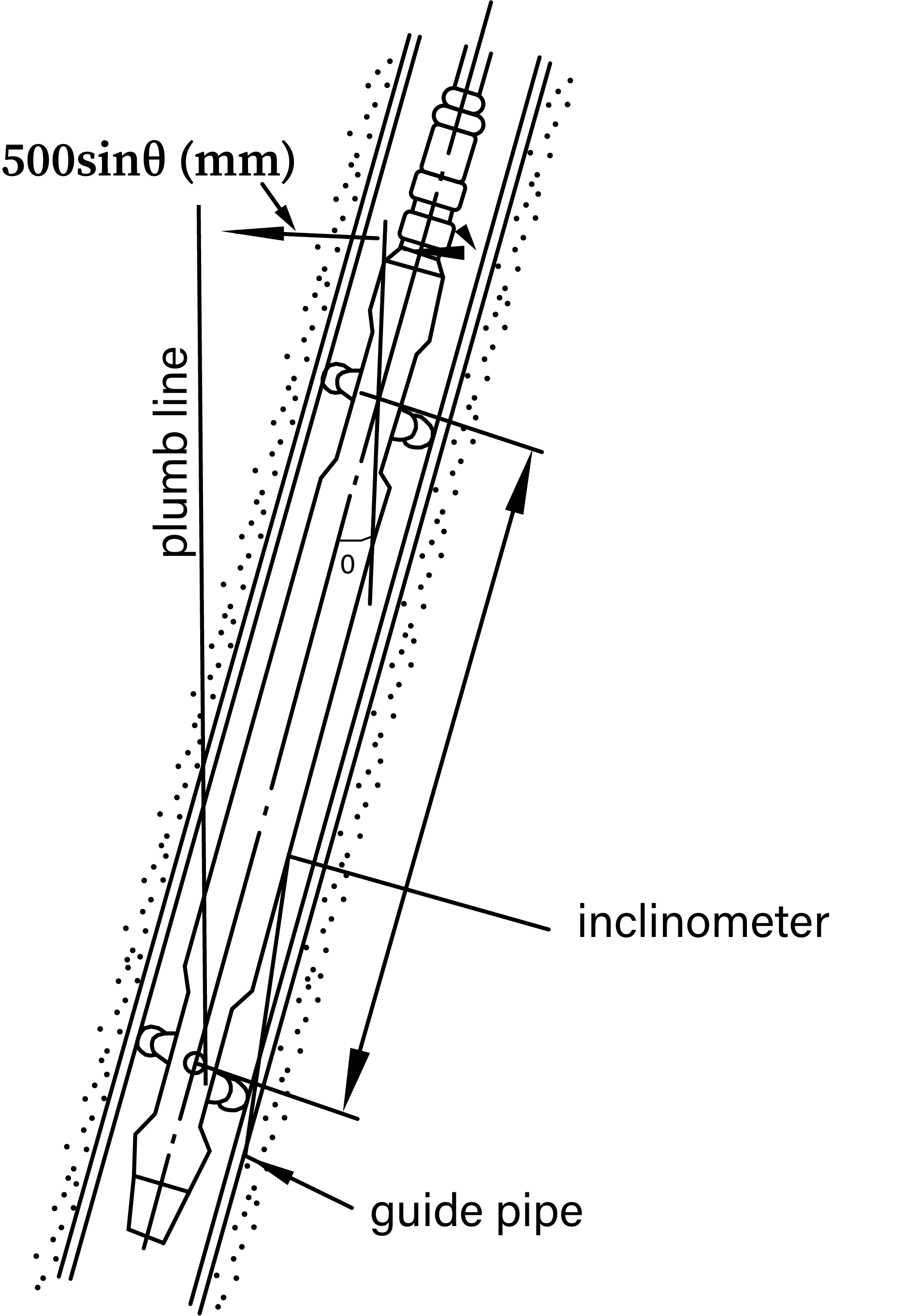

A grooved casing is inserted into the borehole extending into the bedrock formation, and an adequate quality of grout should be placed into the borehole to assure an intimate contact with the borehole. By lowering a probe equipped with a tilt sensor, de· formation in the casing can be detected and movement of a landslide can be determined (Figure 3.3.2.10). An accurate measurement is possible where the deformation of a landslide is relatively small. As a landslide movement increases, the borehole and casing will bend making insertion of the probe difficult or the casing will exceed the tilt detection limit of the instrument.

Figure 3.3.2.10 Sensor of insertion type inclinometer

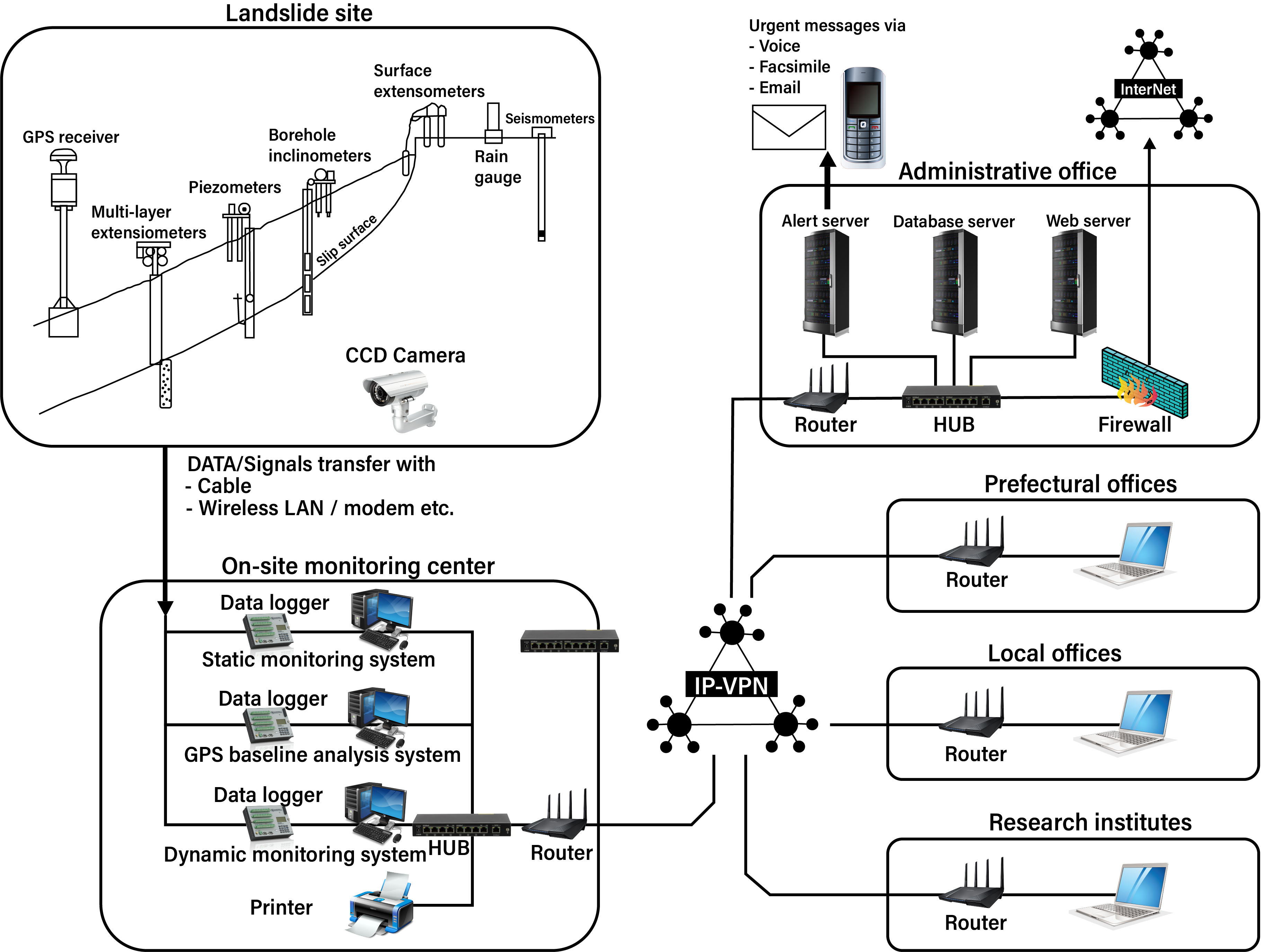

In the past, measurements of slope deformation have been performed manually. More recently, automatic monitoring systems using data loggers and computers are being used. The instrument setup in the field has been designed for easy installation, and is weatherproof, durable, maintenance-friendly and economical.

Here are three main advantages in using the automated survey system:

Semi-automatic systems manually collect data from the data logger and sensor installed at the site on a periodic basis. Data can be retrieved directly from the hard drive of the computer or through flash memory.

Full-automatic monitoring systems permit remote control in real time and rapid graphic data processing and display. It is possible to store long term data accurately and effectively and would provide early warning signs of slide activity, thereby reducing landslide hazards (Figure 3.3.2.11).

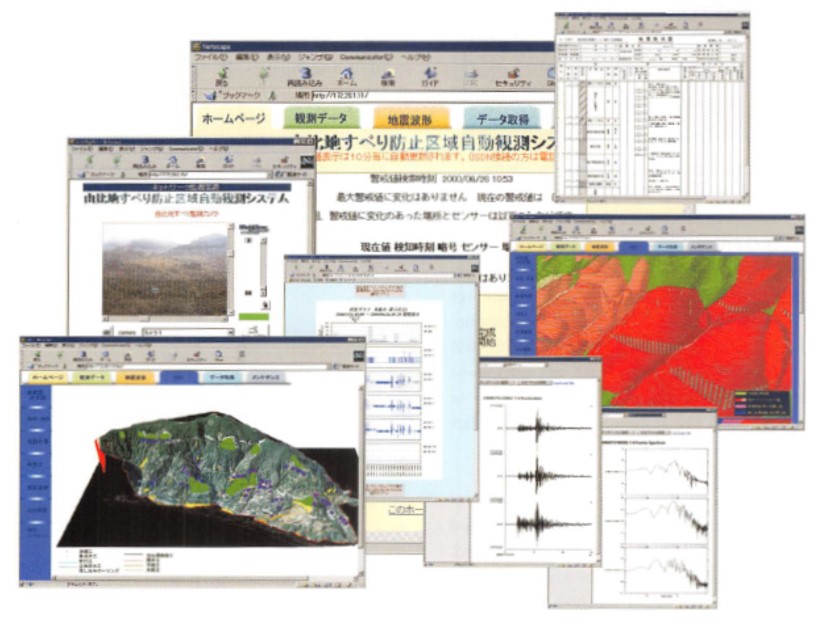

Furthermore, recent developments in the intelligent construction systems at construction sites facilitate real time safety control during construction. In recent years, landslide monitoring systems utilizing information technology along with the existing full-automatic monitoring system and GIS have been developed (Figure 3.3.2.12, and 3.3.2.13).

Figure 3.3.2.11 Examples of landslide movements obtained by various instruments

Figure 3.3.2.12 Automated monitoring system using IT Technology

Figure 3.3.2.13 Automated monitoring system combining with IT Technology and GIS

1 1998 World Health Organization, EMERGENCY HEALTH TRAINING PROGRAMME FOR AFRICA, Panafrican Emergency Training Centre, Addis Ababa, July

2 https://www.undrr.org/terminology/hazard

1 https://www.gsi.go.jp/hokkaido/bousai-hazard-hazard.htm (in Japanese)

2 2004 Public works research institute, Report on Joint Research on Risk Assessment of Road Slopes Using GIS, Draft Guidelines for Preparing Road Slope Hazard Maps, February (In Japanese)

3 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/bousai/main/saigai/tisiki/syozaiti/ (In Japanese)

4 https://www.city.hino.lg.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/002/460/flood_h29_en.pdf

5 2013 Cabinet office of Japan, Guidelines for Volcano Hazard map for disaster prevention, March, http://www.bousai.go.jp/kazan/shiryo/pdf/20130404_mapshishin.pdf (In Japanese)

6 http://www.city.kagoshima.lg.jp/kikikanri/kurashi/bosai/bosai/map/documents/eigo.pdf

7 2021 Headquarters for earthquake research promotion, National Seismic Hazard Maps for Japan (2020), March (In Japanese)

8 2021 Headquarters for earthquake research promotion, National Seismic Hazard Maps for Japan (2020), March (In Japanese) https://www.pwri.go.jp/icharm/publication/pdf/2010/4184_tsunami_hazard_mapping.pdf

9 https://www.mlit.go.jp/kowan/hazard_map/5/shiryou2.pdf (In Japanese)

10 2010 Public works research institute of Japan, Tsunami Hazard Mapping in Developing Countries, November

11 2020 Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism of Japan, Guidelines for developing sediment-related hazard maps, October, https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/sabo/201015_HMguideline_honbun.pdf (In Japanese)

12 http://www.hrr.mlit.go.jp/matumoto/contents/sub/school/saigai_kisomenu.html (In Japanese)

13 2020 World bank, The global landslide hazard map, Final project report, pp50, June

1 2002, OECD, Glossary of key terms in evaluation and results based management. Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/2754804.pdf

2 2011, Koichi SUGA, Recovery From the Damage Caused By the Earthquake -At the Makinohara Section Of the Tomei Expressway, Civil engineering Journal, Vol. 53 No.3, Public works research center, March (In Japanese)

3 2017, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Japan, Inspection Guidelines for Road Earthwork Structures, August (In Japanese) translated into English

4 2013, W. Satoh, Slope failure forecasting methods, Soil mechanics and foundation engineering 61(9), 10-13, 2013-09 September

5 2013, W. Satoh, Slope failure forecasting methods, Soil mechanics and foundation engineering 61(9), 10-13, 2013-09 September

6 2012, Japan Landslide Society, Landslide in Japan(7th Revision)

7 2012, Japan Landslide Society, Landslide in Japan(7th Revision) (In Japanese)

It is important to provide road users with early warning information about disasters. Adequate early warning information can increase public awareness of disasters and prevent loss of life and reduce the economic and material impact of disasters through proactive disaster preparedness and post-disaster recovery efforts. For early warning systems to be effective, they must actively engage communities at risk, promote public education and awareness of risks, effectively spread messages and warnings, and ensure that they are always ready. Particularly in recent years, as disasters due to extreme weather events tend to be more severe and widespread, efforts are being made to develop early warning information as a means of maximizing the use of existing road infrastructure to reduce disasters, in addition to organizing disaster-resistant road infrastructure.

Early warning information provision currently includes those for floods, earthquakes, avalanches, tsunamis, tornadoes, landslides, and droughts. Some of the road authorities provide their own early warning systems for specific disasters listed above. The objectives of early warning information provision can be divided into two categories: damage deterrence and damage impact reduction 1.

The purpose of damage suppression is to minimize the occurrence of disasters by providing information on the possibility of disaster occurrence in advance and preparing for it. This includes rainfall information and typhoon forecasts. On the other hand, "damage impact reduction" is to prepare for the damage that has occurred in order to cope with the situation and reduce the impact of the disaster afterward. It corresponds to the damage prediction immediately after the earthquake. It is desirable to provide both types of early warning information, but it is necessary to consider providing information according to the situation in each country.

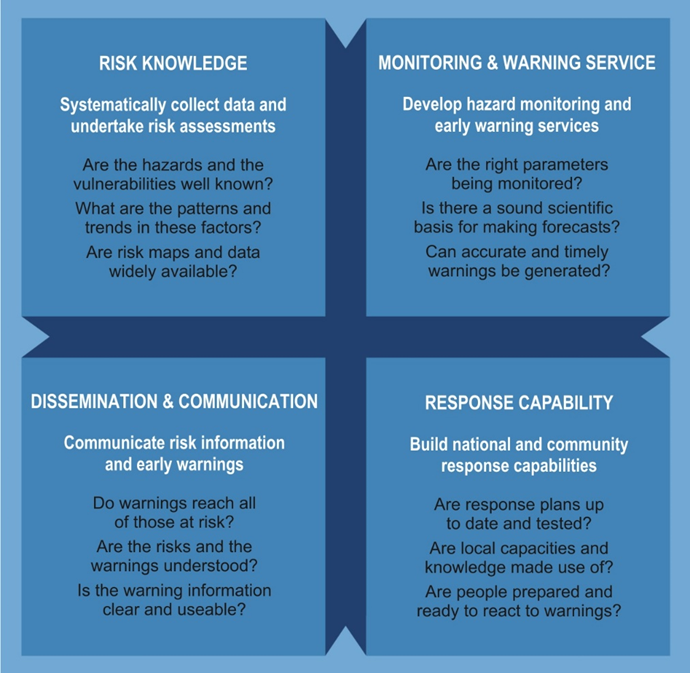

An early warning information system is "an integrated set of systems and processes for hazard monitoring, forecasting and prediction, disaster risk assessment, communication, and preparedness activities that enable individuals, communities, governments, and businesses to take timely action to reduce disaster risk in advance of a hazardous event” 2.

In 2003, experts taking part in the 2nd International Early Warning Conference 3 introduced the current concept of efficient or people-centered early warning systems based on four elements:

This concept is shown in Figure 3.4-1. 4

In this section, early warning information systems implemented in the road sector are introduced.

Figure 3.4-1. Four levels of early warning system: UNDRR

Road networks are very important social infrastructure for economic, social, environmental and security reasons. However, the frequent and severe flooding associated with recent extreme weather events has had a significant impact on the transportation system and its users. Many lives have been lost when cars are swept away by flood waters and drivers are unable to escape from their vehicles in time. In addition, it sometimes leads to massive blockage of roads. Thus, flooding is one of the most important threats to road management.

Figures 3.4.1.1 1, 3.4.1.2 2, 3.4.1.3 3 and 3.4.1.4 4 show examples of damage to roads caused by floods. Flooding in creeks and depressions, flooding caused by sediment runoff along with stream water, and flooding of underpasses due to the construction of multi-level roads in cities are all common. The problem of scouring due to flooding is a long-standing effect of flooding.

Figure 3.4.1.1. Water Flood in Texas, USA

In many countries, flood and flash flood warnings are issued when weather conditions are expected to bring very heavy rainfall that may cause flooding or flash floods. Similar weather warning information systems are in place in the United States, Europe, Australia, Japan, and other countries. A flash flood warning means that weather conditions indicate a significant and high probability of flooding risk. A flood warning means that there is a high probability that local waterways will soon be flooded.

Figure 3.4.1.2. Mud flow flood in California, USA

In the United States, flash flood warnings and flood watches are in place. In Canada, a heavy rainfall warning, which indicates that rainfall is expected that may cause flooding, is essentially the same thing as a flood warning. In Australia, flood warnings issued by the Bureau of Meteorology cover similar conditions to flood warnings in the United States. In Europe, there is the European Flood Warning System. In Japan, there is a warning system that includes special alert information.

Figure 3.4.1.3. Flooding of autoroute Décarie – Torrential rain in Montréal (July 14, 1987)

It is difficult to estimate the depth of water on flooded roads, and this has led to many accidents where cars enter flooded roads and get stuck. In addition to such direct damage, indirect damage such as economic loss due to detours along flooded roads has also occurred.

Figure 3.4.1.4. Bridge scouring - High Floods on Dornesti Bridge, Suceava, Romania

In the case of roads, together with weather warning information, the emphasis is not on predicting the occurrence of floods themselves, but on quickly informing drivers of the effects of flooding on roads. For example, in the event of flooding or flooding, efforts are being made to inform drivers of the effects of the flooding as soon as possible to prevent secondary disasters from occurring.

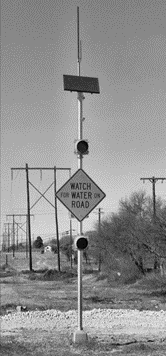

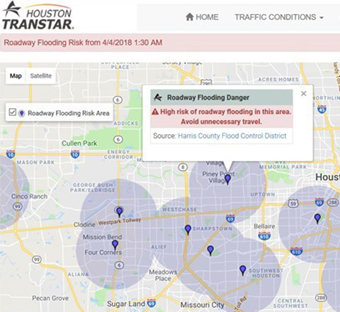

Figure 3.4.1.5 5 shows a warning system that informs road users in advance of flooding. Figure 3.4.1.6 6 shows an example of the installation of road surface markings to warn road users of flooding in urban underpasses. Figure 3.4.1.6 shows an example of the installation of a VMS for warning information. Furthermore, Figure 3.4.1.7 7 shows an example of a real-time flood warning tool to inform drivers of high-risk flood areas during severe storms. The Houston Transtar website and traffic map had over 3 million visitors during 2017 Hurricane Harvy and provided information to travelers when deciding on a route through the Houston area 8.

Figure 3.4.1.5. Advance Flood Warning System

The development of a flood warning system is now underway to enable proactive monitoring, assessment and response to flood-related disasters and associated hazards in real time. If the impact of flooding on roads can be predicted in advance, limited resources can be prioritized to close roads, detours can be planned, the public can be informed before motorists are exposed to flood hazards, and travelers can avoid delays and demands on road capacity during the worst times. These active approaches will be presented in the case studies.

Figure 3.4.1.6. Flood and flood depth sign for underpass road

Figure 3.4.1.7. Roadway flooding information (Houston TRANSFER)

Dry season will create wild fires and result in devastating damage in some area. The path and expansion of the fire is difficult to predict due to topography and wind direction, which can make it difficult to set up appropriate road closures and detours. Figure 3.4.2 1 shows the closed road by wild fire. If it is possible to predict the likelihood of a fire and the path and expansion of the fire, it will be easier to ensure the safety of site workers and road users, to procure materials to minimize the impact on the road, and to implement temporary road closures. The such fire warning system is going to be developed.

Figure 3.4.2. Road ways closed by wild fire

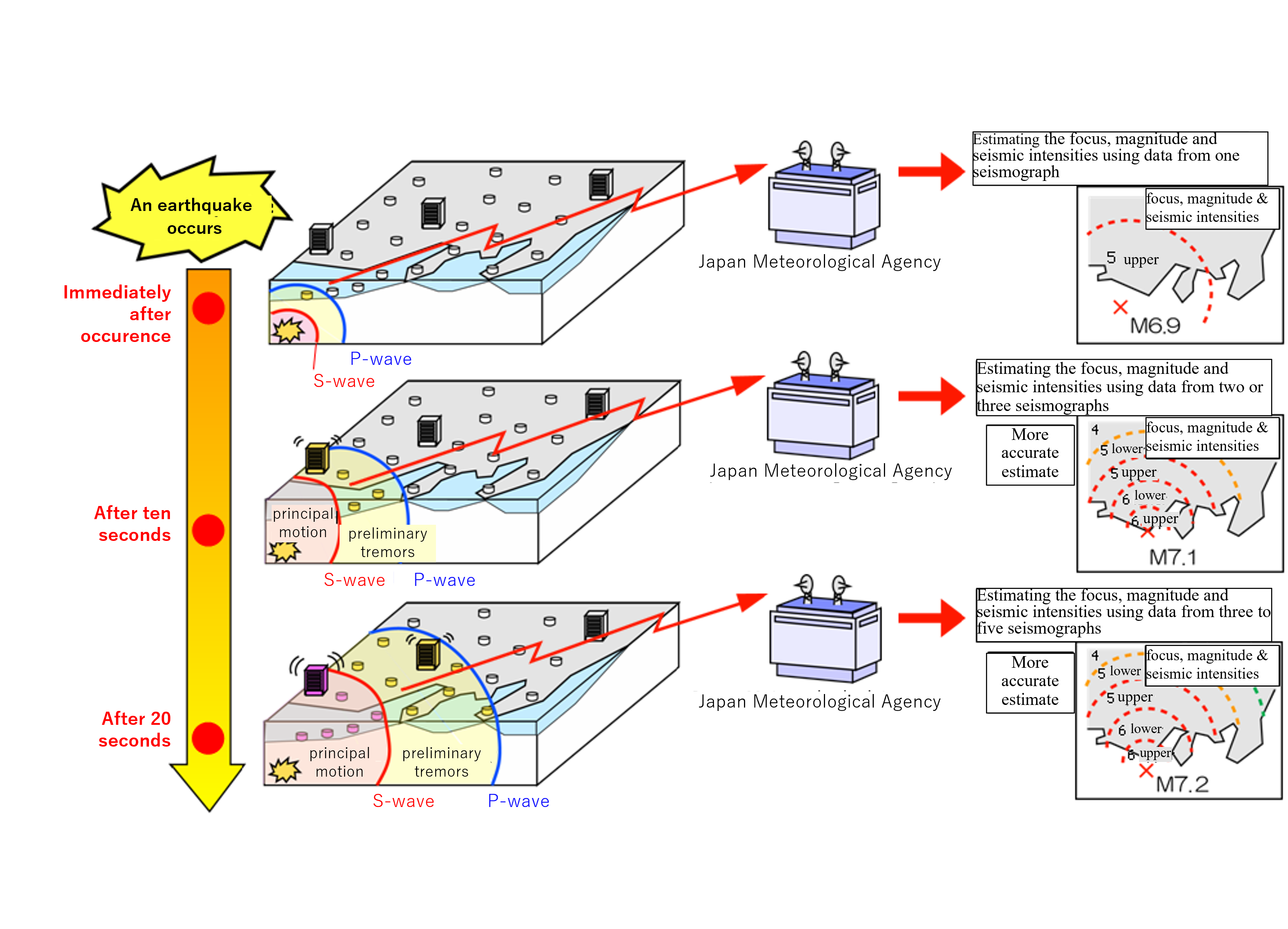

An earthquake early warning system is "to quickly analyze the distribution of seismic source elements and seismic motions after an earthquake has occurred, and to convey this information to road users for use in road disaster prevention.

There are two main types of systems: early warning systems, which aim to predict the magnitude of shaking before the main motion of an earthquake and prepare for it, and early earthquake damage estimation systems, which predict the extent of damage based on the intensity of the shaking.

In the early warning system, the location of the epicenter and the scale of the earthquake are estimated immediately after the occurrence of the earthquake by analyzing the seismic wave data captured by seismographs at observation points close to the epicenter. The system is designed to help mitigate earthquake disasters by providing information on the seismic intensity as soon as possible. For earthquakes with distant epicenters (trench earthquakes, etc.), a certain amount of grace time can be expected in principle. On the other hand, for earthquakes with close epicenters (e.g., direct-type earthquakes), a grace period may not be expected near the epicenter. Since the development of a wide-area observation network is a prerequisite, national meteorological agencies and similar organizations are developing early warning information. In the road sector, there have been no cases where early warning systems have been developed independently. Many road managers use the early warning earthquake information provided by national meteorological forecasting organizations for their road operations.

The early earthquake damage estimation system uses seismic wave data recorded by seismographs placed at the site immediately after the occurrence of an earthquake and data on the ground and structures prepared in advance to estimate the extent and scale of damage to the roads. By estimating the degree and extent of damage, the system supports the prioritization of emergency activities. Many road managers have adopted the early earthquake damage estimation system. This system can also perform damage simulation by using scenario seismic waves. The results of the simulations can be used to develop a rational disaster prevention plan.

Figure 3.4.3 1 shows the image of the mechanism of the earthquake early warning system.

Figure 3.4.3 Mechanism of the earthquake early warning system

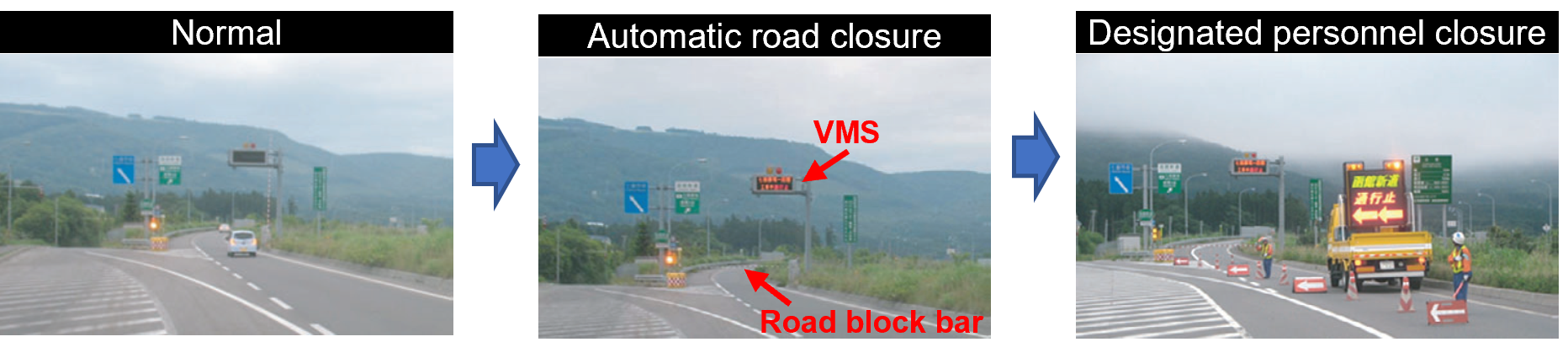

Road traffic closure and control have a great impact on local life and economic activities. Therefore, ensuring the functioning of roads is an important mission of road administrators. On the other hand, it is also an important mission of road managers to secure road safety and road users by controlling or closing the road traffic when there is a concern about safe road use such as during adverse weather conditions. In recent years, due in part to the effects of climate change, there has been an increase in localized and concentrated heavy rainfall in short periods. One of the important issues for road administrators is to prevent road users from being involved in landslides and other accidents caused by such extreme weather, especially during extreme torrential downpours. According to this background, it has been widely considered to restrict the use of roads in advance in order to ensure the safety of road and road users.

In Japan, based on the above concept, since 1969, pre-event road closures and traffic control systems have been implemented by designating areas where damage may occur or is likely to occur in the event of adverse weather conditions. When the threshold of extraordinary weather conditions is exceeded, road administrators close the road or control the traffic in order to ensure the safety of road and road users 1. In this section, an overview of Japan's pre-event road closures and traffic control system for heavy rainfall is introduced.

In Japan, the designation of pre-event traffic control and closure sections began in the late 1970s. In 1977, the peak year, 224 sections of 1,379 km were designated. As of April 2015, 980 km of 175 sections have been designated as pre-event traffic control and closure sections.

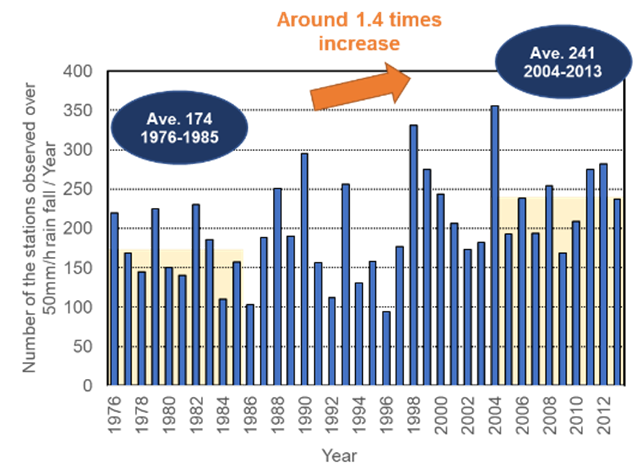

On the other hand, rainfall is becoming more localized and concentrated, according to the fact that the amount of rainfall exceeding 50 mm per hour, which is known as short-time torrential downpours, has increased 1.4 times in the last 30 years as shown in Figure 3.4.4.1. As a result of these changes in the weather, there has been an increase in the number of disasters such as landslides caused by sudden heavy rainfall and road closures, which have not been seen in the past. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the thresholds for pre-event traffic control and closure sections to cope with short-term torrential downpours 2.

Figure 3.4.4.1. Annual trend of hourly precipitation in Japan

Figure 3.4.4.1 shows the annual number of occurrences of hourly precipitation of 50 mm/h or more in Japan (per 1000 observation points) 3.

The following two methods are used to set the threshold for pre-event road closure and traffic control against heavy rainfall.

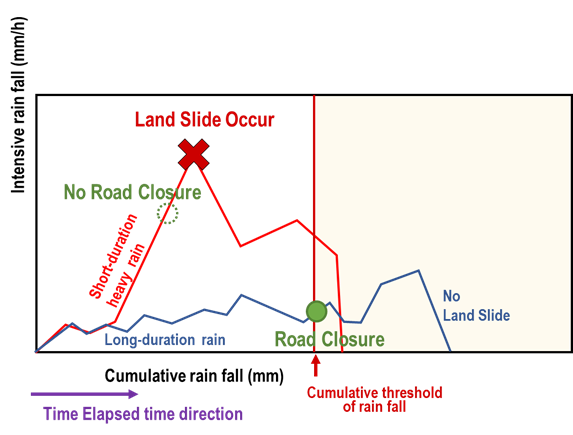

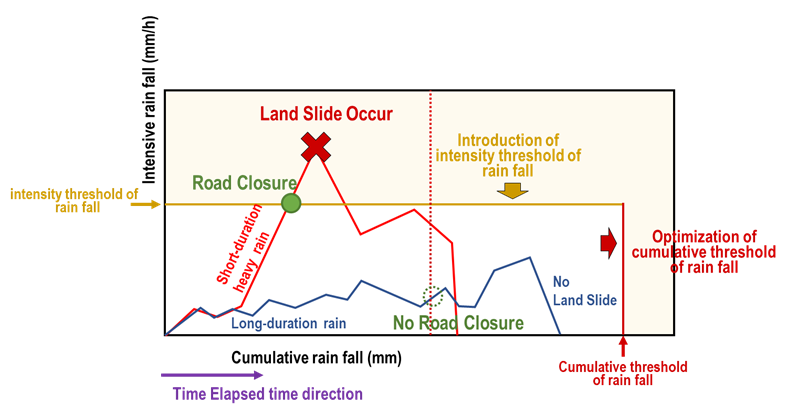

A road closure is imposed when the accumulated rainfall exceeds a threshold value. If there is no rainfall or very little rainfall (e.g., less than 2 mm per hour) for a certain period of time (often 3 hours), the accumulated rainfall is reset to zero. Figure 3.4.4.2 shows the schematic image of the cumulative rainfall method 5.

Figure 3.4.4.2 Current road closure threshold- Schematic image of the cumulative rain fall method