On March 11, 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred. The magnitude (Mw) of the earthquake was 9.0 to 9.1, the largest ever recorded in Japan. A maximum seismic intensity of 7 was observed in parts of Miyagi Prefecture. The main quake, the resulting tsunami, and subsequent aftershocks caused tremendous damage throughout eastern Japan, from the Tohoku region to the Kanto region. Many people lost their lives.

The tsunami reached the coast of Iwate Prefecture about 25 minutes after the earthquake. Its speed is said to have reached several tens of kilometers per hour.

The maximum wave height was recorded at 9.3 meters at the port of Soma in Fukushima Prefecture 1, and the run-up height, which indicates the height up a slope, was 40.5 meters in the Shigemoe Aneyoshi district of Miyako City 2, the highest ever recorded in Japan. Analysis by Tohoku University revealed that the tsunami had traveled up the Kitakami River to a point about 49 km from its mouth 3.

Miyako Road, a 4.8-km section of the Sanriku Expressway, opened in March 2010. When the tsunami hit the area, about 60 residents managed to escape by climbing up the expressway embankment.

The Kamaishi–Yamada Road, a 23-km section of the Sanriku Expressway that was opened only six days before the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, served as a disaster management road. It was built to ease traffic congestion on Route 45, the main road connecting the coastal communities. Since Route 45 was prone to flooding from typhoons and tsunamis, the new road was expected to provide an alternative route if Route 45 were cut off in an emergency. In the Unosumai District of Kamaichi City, about 570 residents and school children escaped the tsunami. Because the road that led to the evacuation shelter had been destroyed, they climbed up to the Kamaishi-Yamada Road and managed to reach the evacuation shelter safely. Figure 4.4.6-1 4 shows photo for the residents who evacuated on foot along the Kamaishi-Yamada Road (Motor road).

Figure 4.4.6-1 Residents evacuate on foot along the Kamaishi-Yamada Road (Motor road).

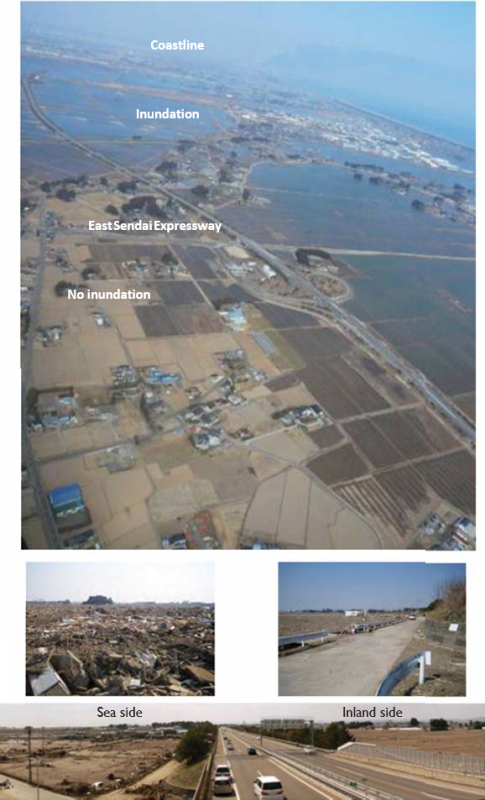

There is a similar report on the Sendai-Tobu Road, which was hit by a tsunami in the 2011 East Japan Earthquake, and several people evacuated to the Sendai-Tobu Road by running up the slope and climbing over the entry barrier, and survived 5. As shown in Figure 4.4.6-2 6 7, a lot of the people could be seen on the expressway during the tsunami.

According to the world bank report, it is indicated that roads, highways, and expressways provided safe evacuation sites and escape routes because they were designed with earthquakes and tsunamis in mind. It pays to take disaster reduction into account when designing transport and other infrastructure 8.

Figure 4.4.6-2 Evacuation situation on Sendai East Road (embankment)

There seems to be a room for improvement on tsunami evacuation from the road administrator point of view. This section will give you some ideas.

Tsunamis are caused by the uplift and subsidence of the seabed caused by earthquakes, and the upward and downward movement of seawater in the surrounding area. Because tsunamis move all the seawater from the sea bed to the sea surface, and because their wavelengths are very long, ranging from several kilometers to several hundred kilometers, the seawater becomes a huge mass of water that rushes to the coast 1.

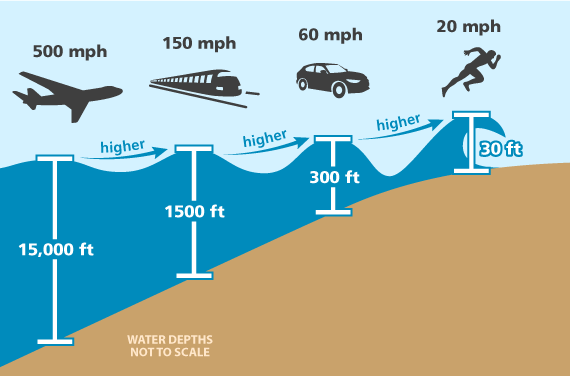

The speed of a tsunami depends on the depth of the water it’s traveling through. The deeper the water, the faster the tsunami. In the deep ocean, tsunamis are barely noticeable, but they can move as fast as a jet plane, more than 500 mph (800 km/h). As they enter shallow water near land, they slow to approximately 20 mph (36 km/h), which is still faster than a person can run.

As tsunamis slow down, they grow in height. When they arrive on shore, most are less than 10 feet (3 m) high. In extreme cases, they can exceed 100 feet (30 m) when they strike near their source. Large tsunamis can flood low-lying coastal areas more than a mile inland 2.

Figure 4.4.6.1 2 shows an illustration of the relation between tsunami height and speed.

Figure 4.4.6.1 Speed of tsunami waves compared to common means of transportation

As in any other disaster, self-help is the most important way to protect yourself from tsunami. It is essential to know how each individual should act to protect his or her own life from a tsunami, especially a nearshore tsunami.

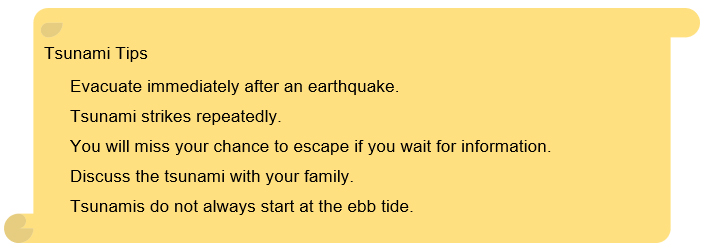

Table 4.4.6.2 shows the very important tsunami tips developed in Kushimoto-town 3.

Table 4.4.6.1 Tsunami Five Tips

When in a low elevation area, it is important to be aware of tsunamis whenever there is an earthquake, even if you are far from the coast. Tsunamis run up along the ground to higher elevations, and in the 2011 East Japan Earthquake, run-up heights of up to 40.1 meters were observed. When the epicenter is close, tsunamis may surge immediately after the earthquake. In the case of the 1993 Hokkaido Nansei-Oki Earthquake, a tsunami hit Okushiri Island shortly after the earthquake, killing many people. As a general rule, when an earthquake strikes, evacuate immediately from the coast to outside the expected flooding area 3.

Tsunami strikes repeatedly. The height of the tsunami is often higher in the second and third waves. After evacuating to higher ground, it is important to avoid returning to your home from the evacuation site because the tsunami did not come, or because the tsunami that did come was not very high.

In the case of far field earthquakes, tsunamis will hit after a long period of time, such as the 1960 Chile earthquake, which killed 119 people in Japan when a 6-meter tsunami hit after a very long time. In the case of distant earthquakes, there is a certain amount of time before a tsunami strikes, so it is necessary to obtain appropriate disaster prevention information 3.

The power of a tsunami is very strong. A healthy adult can be swept away by the surging water even if the height of the water is only 20-30cm. Also, the rivers are unobstructed, so they move further inland than the city. It is also important to evacuate in a direction away from the river, as tsunamis may hit from the river rather than from the sea. It is essential to evacuate to a safe place such as high ground as soon as possible 3.

It is important for families to decide on evacuation sites, evacuation routes, and emergency communication methods on a regular basis. It is a good idea to refer to the tsunami hazard map published by the municipality in which you live, and decide on the places where your family will meet in case of a disaster.

When evacuating due to a tsunami, be aware that evacuation should be to a "higher" location rather than a "farther" location. It is also important to consider multiple evacuation sites and routes, as roads may be impassable due to collapsed buildings or fires. As a general rule, it is better to evacuate on foot, since evacuation by car may cause traffic congestion. It is essential to evacuate to a "tsunami evacuation building" that is located above the expected tsunami inundation height, or to a building that is as sturdy and tall as possible 3.

It is very dangerous to go to the coast to see if a tsunami is coming, mistakenly believing that it will start at the ebb tide; the 1993 Hokkaido Nansei-Oki Earthquake, the 2003 Tokachi-Oki Earthquake, and even the 2004 Sumatra Earthquake in Sri Lanka and India saw tsunamis surge in without a previous ebb tide. There have also been reports of tsunamis flowing up rivers or back down drains, overflowing manholes and gutters. Even if you are far from the coastline, it does not mean you are safe 3.

Structural measures include relocation of villages to higher ground, construction of seawalls, and lock gates to make towns more resistant to tsunamis. It is also important to create a town that is easy to evacuate.

Infrastructure and public facilities such as roads, highways, and railways can be used as disaster management facilities in the event of floods, tsunamis, mudflows, and landslides. Facilities that are multifunctional are a particularly cost-effective approach to disaster management. Integrate various facilities into planning for disaster risk management (DRM). DRM plans should include a range of public facilities. For example, playgrounds and parking areas can become rescue team bases or spaces for transition shelters. Expressway embankments can become evacuation sites in the event of cyclones, floods, and tsunamis 1. Figure 4.4.6.2.1 shows the photos of the East Sendai Expressway that acts as a multi-functional road with a function of tsunami barriers.

Figure 4.4.6.2.1 East Sendai Expressway acted as a Multi-functional road with a function of tsunami barriers

Tsunami seawalls are designed to protect towns from tsunamis by enclosing the residential areas with high levees and blocking them from the sea. However, they are expensive to build, have a negative impact on the environment of the bay, and do not completely prevent tsunamis from inundating residential areas 1.

The primary measure against tsunamis is to move away from them. The most effective way to do this is to relocate the city itself to higher ground, which has been recommended for many years. In the areas affected by the 2011 East Japan Earthquake, housing relocation to higher ground has been promoted, especially in the areas that were severely affected by the tsunami. In order to relocate the houses to higher ground, 324 housing complexes have been constructed in 27 municipalities, and 8,389 housing lots have been built 2.

Land-use regulations, including those that relocate houses to higher ground, are successful but sometimes difficult to implement. For that reason, alternative measures need to be considered. Relocation deeply affects the livelihoods and daily lives of many people 3.

When a tsunami strikes, the primary rule of evacuation is not to move away from the tsunami along a plane, but to move up to higher ground than the tsunami.

There are towns that have been built with tsunami evacuation in mind. In these towns, the movement of people from the beach to the mountains at the time of tsunami evacuation intersects with the life path in normal time along the beach. At intersections, stopping to check and slows down walking speed for evacuation. Therefore, the corners of all crossroads were cut off to create streets where people can see both sides of the road while running.

In some cases, it is better for residents to build evacuation routes than for the government to do so. In one town, instead of a 15-minute evacuation route, the residents built their own route that took only six minutes.

For evacuation routes, signs that can be seen in the dark and work even during a power outage are needed, and solar-powered signs are encouraged 4.

In order to mitigate the damage caused by tsunamis, it is necessary to improve the self-defense capability of local residents against disasters through the provision of hazard information and other non-structural measures, in addition to the structural measures such as conventional development of coastal protection facilities.

A tsunami hazard map is a map that shows the areas that are expected to be damaged by tsunamis and the extent of the damage, along with disaster prevention-related information such as evacuation sites and routes, if necessary.

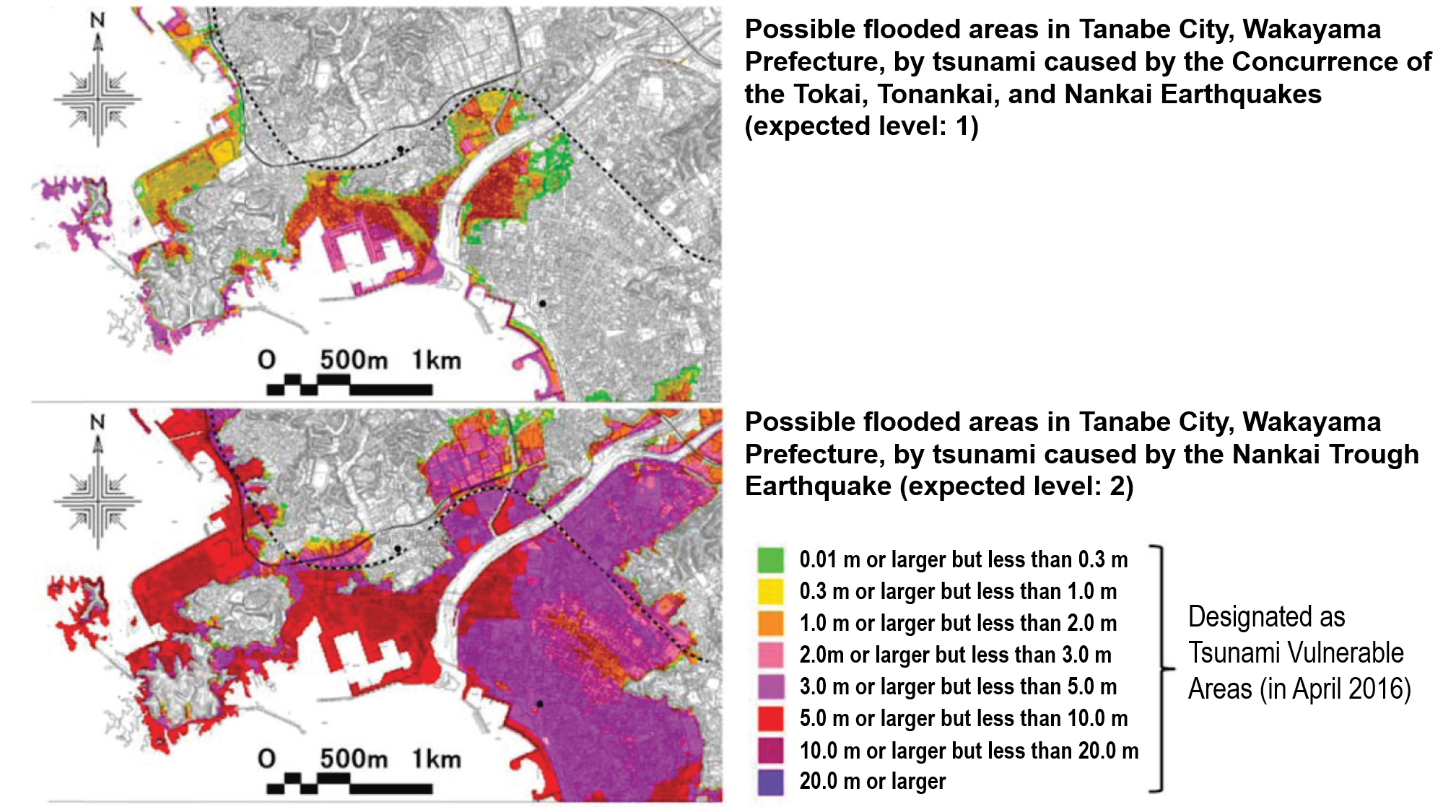

Table 4.4.6.2.1 5 6 is the tsunami design considerations Japan developed after the lessons from 2011 East Japan earthquake and ensuing tsunami.

Figure 4.4.6.2.2 7 shows an example of the tsunami level considered for tsunami hazard developing.

| Frequency of Occurrence | Policy |

|---|---|---|

Level 1 | Occurring roughly once in tens of years to over a hundred years | In addition to protecting human life, the government should develop or improve coastline preservation and other facilities from the viewpoint of protecting the property of residents, stabilizing the economic activities of local communities, and maintaining production bases effectively. |

Level 2 | Occurring roughly once in hundreds of years to a thousand years | The government should establish comprehensive tsunami measures using all possible resources, giving top priority to the protection of the lives of residents, etc., and focusing on evacuation. |

Source: This table has been created using a report of the group of experts organized by the Central Disaster Management Council to investigated earthquake and tsunami measures using lessons learned from the Great East Japan Earthquake (September 28, 2011)

Figure 4.4.6.2.2 Examples of expected areas flooded by Two Tsunamis (level1 and Level 2)

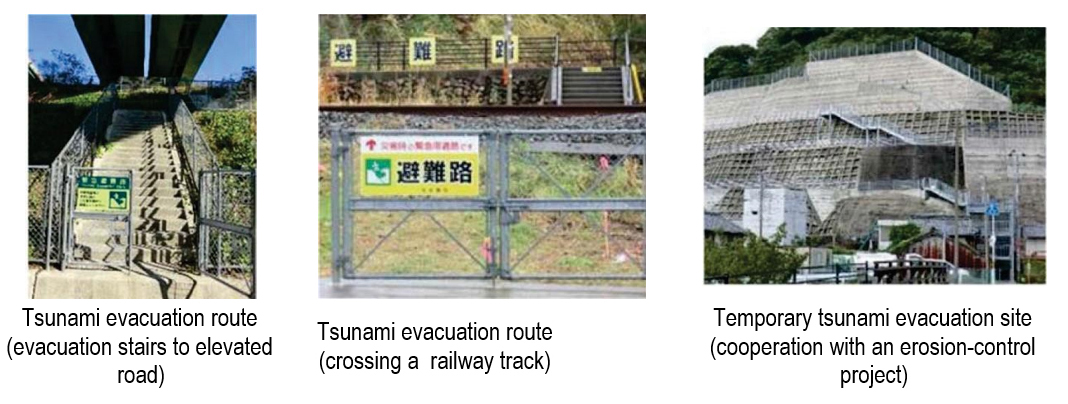

It is very important to improve facilities for evacuation in cities along the coast. Currently, tsunami evacuation facilities can be categorized into the following; 1) tsunami evacuation tower, 2) tsunami evacuation building, 3) cooperation with public projects, 4) measures against the points that interrupt evacuation, and 5) providing materials for the improvement of evacuation routes by groups in local communities with dwindling populations.

Table 4.4.6.2.2 (Selectedly referenced to 8) shows the tsunami evacuation facilities cooperated with road related projects.

Table 4.4.6.2.2 Tsunami evacuation facilities cooperated with road related projects

Tsunamis are usually generated by great subduction zone earthquakes when the ocean floor is rapidly uplifted during the earthquake. The tsunami wave from a local subduction zone earthquake will arrive at the coast in approximately 10-20 minutes, and tsunami waves will continue to arrive periodically for several hours. When the shaking stops, people must immediately move inland to high ground. It is critical that residents and tourists know the landward extent of the local tsunami inundation zone used on evacuation brochures, their evacuation routes, and the nearest safe zones.

There are several categories of tsunami signs available:

An end-to-end evacuation route plan consists of (A) ‘You Are Here’ signage and route guidance for high traffic sites; (B) guidance signage established at the start of the route used in Cannon Beach and visible from the beach, as well as signage on posts along the route; (C) signage may also be painted on roads or footpaths with distance to safety identified; and finally (D)signage indicating that you have reached your safety destination (escape point) and have the inundation zone needs to be identified along every evacuation route (E). Table 4.4.6.2.3 9 shows the tsunami evacuation signs indicated from (A) to (E).

Table 4.4.6.2.3 Tsunami evacuation signs

It is important for the government and residents to conduct disaster simulation exercises together on a regular basis. In addition to general disaster exercises, special tsunami evacuation drills are sometimes conducted. In some places, drills are held involving tourists. It is important to confirm evacuation routes and locations in advance. It is also important to consider the issue of evacuation assistance for vulnerable people, such as the elderly and those in depopulated areas.

According to the final report of the Countermeasures for Earthquakes and Tsunami Based on the Lessons Learned from the 2011 Off-the-Pacific-Coast-of-Tohoku Earthquake, considerations on Tsunami countermeasures are discussed and summarized 1, 2.

First of all, as a premise, a tsunami is categorized into Level 1 (L1) and Level 2 (L2) when the scale of and measures against tsunami are considered. For the largest-scale L2 tsunami, which occurs extremely rarely but produces immense damage like the last one, every possibility, including the maximum levels, shall be considered. Consequently, comprehensive measures against tsunami shall be established that give priority to the protection of the lives of residents and that implement every possible measure for the evacuation of residents. For the L1 tsunami, which occurs comparatively frequently and where the height is low but produces serious damage, coastal protection facilities shall continue to be developed and improved from the viewpoint of protection of the property of residents and stabilization of economic activities in the local areas, in addition to the protection of human life.

A basic principle for the mitigation of damage caused by L2 tsunami is to combine tangible and intangible measures. Especially in the areas that are at risk of being hit by tsunami soon after an earthquake, the town shall be designed to ensure that residents evacuate in about five minutes. To be concrete, the following are suggested:

A working group established by the Cabinet Office to study tsunami evacuation measures had a careful discussion and came up with the following basic ideas for tsunami evacuation 3.

It is important to recognize that tsunamis are a natural phenomenon, and that there is always a possibility that a tsunami will strike.

Quick evacuation is the most effective and important tsunami countermeasure. In addition, structural measures, such as the construction of coastal protection facilities, and non-structural measures, such as reliable information dissemination, should all be positioned as measures to support quick evacuation.