Recovery activities repair road damage from an emergency caused by a disastrous event and deliver the road function to its pre-disaster state or a more resilient state.

Recovery refers to the activity that restores the road function lost due to the disaster. Response focuses on the recovery of road functions necessary for emergency operations, while restoration involves restoring the functions to a state that meets the needs of the disaster situation and society. Recovery should have resilience-enhancing goals that consider lessons learned from the disaster and feedback for future mitigation activities. Recovery is the activity that is carried out after the occurrence of the emergency, in parallel with the response.

Recovery is closely related to the direction of post-disaster social development that needs coordinated goals, while mitigation, preparedness, and response have relatively clear goals. Recovery involves complex issues and decisions that must be made by individuals and communities. Recovery needs to balance the urgent need to recover communities to their pre-disaster state with the long-term goal of reducing future vulnerability and increasing resilience. Resilience includes improving materials and construction methods to make infrastructure more resilient, establishing redundancy in the transportation network, using Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS), and improving the common links between transportation and communities. In recovery, it is important to achieve a network that can absorb the damage from future disasters and recover quickly after an emergency. This will be accomplished in close coordination with stakeholders.

Recovery requires close dialogue with national, regional, and community partners.

Recovery measures, both short term and long term, aim to return vital life support systems to a minimum operating standard. The recovery phase in disaster management consists of two activities, namely rehabilitation and reconstruction. Rehabilitation is the repair and restoration of road and bridge infrastructure at an adequate level in post-disaster areas. Reconstruction is an act of physical condition recovery through the permanent rebuilding of road and road infrastructure so it can return to its original condition or even better than before the disaster. Figure 5.1-1 is an example of damage caused by a tropical cyclone in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia.

Figure 5.1-1 Tropical cyclone damage in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

The Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) is a series of activities to aid with impact and needs assessments, which form the basis of an action plan for rehabilitation and reconstruction. Estimated needs is a calculation of the costs required to carry out rehabilitation and reconstruction activities. The PDNA is important because it serves as a record of the damage caused by the disaster, provides estimated losses for use in the calculation process for rehabilitation and reconstruction, and descriptions or evidence of the benefits that will be obtained from mitigation activities. The PDNA is an essential part of the process. The steps and objectives consist of 1 :

This stage has the objective of guiding the authorities to take PDNA activation steps and guide the authorities to compile a frame of reference for PDNA activation. This stage has an output PDNA activation decision and PDNA Terms of Reference.

The purpose is to guide the authorities to set up a PDNA work team and guide the work team to prepare PDNA methods and tools. This stage has an output. The PDNA work team and the appropriate PDNA methods and tools with field conditions.

The purpose is to guide the PDNA work team to implement collection of data on the effects of and impacts on post-disaster needs. The output from this stage is the availability of field data.

The purpose is to guide PDNA work team to conduct assessments of disaster effects, disaster impact assessments, and needs assessments for post-disaster recovery. The output at this stage is the result of the impact assessment – impacts and post-disaster needs.

The purpose is to guide PDNA work team to compile a PDNA report. The output is PDNA periodic reports.

Furthermore, road transport management is needed to accommodate updated post-disaster data and prediction of funds. Implementation of safe evacuation routes needs to identify locations that are not susceptible to disasters; for example, the route must consider the contour/elevation (to anticipate tsunami or tidal flood), far from the slope (to anticipate earthquake or landslide or Nalodo), and must be supported by an advanced road and bridge technology to achieve 2 :

The example of semi-permanent bridge in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia, can be seen in Figure 5.1-2.

Figure 5.1-2 Semi-permanent bridge (Benanain) in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

Recovery strategy can be implemented through three different steps 1.

Urgent needs in disaster areas are food, sanitation, shelter, and medicine. However, it is imperative to tackle the recovery process as early as possible to reduce the direct and indirect impacts of disasters on rural livelihoods and local economies. Planning the recovery process requires some basic data on the extent and impact of a disaster. The first step is to generate this information to plan for the effective rehabilitation and/or reconstruction of the affected area. During the assessment stage it is necessary, as soon as possible, to:

The collection and compilation of information about the road network is not always an easy task. Usually the road network inventory is unavailable or not updated. Little information is available on the extent of the damage and its impact on livelihoods. However, the initial assessment must produce rapid results that will direct specific project interventions. The initial assessment should look in more detail at the rehabilitation and reconstruction tasks that will be required in the affected areas to restore the transport system. Road maps and road inventories need to be prepared to assess the extent of the road network, classification, damage caused, and rehabilitation and reconstruction needs and priorities. An inventory needs to be made based on the technical characteristics of the required rehabilitation and reconstruction tasks for roads and bridges. This can then be used to identify appropriate techniques and complementary light equipment that may be required. For example, while most international experience with labor-based road works is with dirt and gravel surfaces, there have been significant advances recently with more durable asphalt. Similar design innovations can be found in low-cost bridges, especially those suitable for community-level structures. Different road conditions require different technologies.

The main problem in the affected areas is the mobilization of local support needed to rebuild the road network. Communities, contractors and local governments all lost skilled manpower, capital, and assets during the disaster. It is important to first assess the scale of this loss before planning a program to strengthen the capacity of local governments, small-scale contractors, and community groups to carry out necessary road works and contribute to the reconstruction process.

Reconstruction of the road network must immediately meet the access and needs of public transportation. A planning process is needed where these needs can be identified quickly. The process covers the general needs of the community, and most importantly reflects the needs of the poorest and most affected members. Access to essential social and economic services generally affected by disasters and improving access to health services, education, information, markets, water, employment, and income generation opportunities are key factors in mitigating the impact of the crisis.

Integrated Rural Accessibility Planning (IRAP) is a tool that produces a comprehensive plan to improve access situations for communities, regions, and/or areas. The planning process culminates in the creation of an Accessibility Action Plan (AAP) for a specific administrative level. AAP is based on a systematic consultative process with community informants, including leaders, vulnerable groups, responsible government authorities, and other stakeholders such as NGOs. It takes stock of existing assets so repair and maintenance of these assets will be the first priority for investment. This is by far the best investment, especially when resources are limited. It also avoids creating wish lists for new assets while repairing and maintaining existing assets is ignored. It estimates travel time, travel frequency, and travel costs for social and economic activities. AAP then prioritizes needs for various sectors, such as roads, clean water, health, education, and markets. A detailed investment program is drawn up.

Experience shows that AAP is a useful tool to guide investments that will improve accessibility, which in turn will have a beneficial effect on people's potential to move out of poverty. Usually there is a sizeable “buy in” by stakeholders and investors. Critically, AAP is a tool for linking government development programs with ongoing programs from other sources and by other actors. IRAP is typically used in a "normal" development context. A scaled-down version of the process can be used in crisis situations to quickly identify priorities in a participatory manner. This strategy adopts this “cleaned up” version of the IRAP process for developing AAPs for disaster-affected communities. This AAP will be a key tool to guide immediate investment in infrastructure and will also be useful for long-term reconstruction programs. However, roads will not be planned separately from other required infrastructure. The result of planning is a list of road priorities.

Implementing the strategy starts with the rehabilitation and reconstruction of the road network. Special consideration will be given to the technology and involvement of small-scale contractors and local governments.

With many communities losing their livelihoods as a result of the disaster, it is possible to use labor-intensive investments or a “labor-based approach” for the rehabilitation and reconstruction of physical infrastructure (where economically and technically feasible). The implementation of labor-based physical work can be carried out by small-scale local contractors supervised by local government units. Road works should be based on existing specifications and standards from relevant ministries and government authorities. If the existing specifications and standards do not allow for labor-based work, then approval needs to be sought from the government for the use of more appropriate designs and standards that support the use of labor-based technologies. This could focus on removing debris blocking roads and, as far as possible, improving transport systems to distribute aid and restart local economies.

Community works are works that create assets or reconstruct assets that serve a particular community and address their priorities exclusively. Community works could include such activities as improving the local environment through tree planting and soil conservation measures. The ownership of the outputs is held by the community rather than a line Ministry or some other Government Organization.

Public Works are carried out on district infrastructure and will frequently benefit more than one community. A common example of public works is a road improvement project. The asset belongs to the government and thus to the public, not to the village or community. Labor-intensive technology relies primarily on labor and hand-tools only. In this context, their use addresses immediate social protection needs by means of short term employment through which essential infrastructure works can be implemented, albeit restricted to a narrow range of works. The main objective is to create employment while the construction of infrastructure is often of secondary importance

Labor-Based technology offers an optimal use of labor accompanied by equipment in a cost-effective manner, and to the required quality, thus creating a shift in balance between labor and equipment in the way the work is specified and executed. The use of labor-based methods will assist in addressing immediate job creation needs, but also in the longer-term be applied to recurrent works under regular budgets of the infrastructure Ministries. By shifting wisely and carefully from the current conventional equipment-based work methods to more labor-based approaches for selected works components, it will be possible to create significant numbers of jobs and reduce poverty in a sustainable manner without compromising on the quality of the works and without affecting the timeliness and cost of the works. This strategy recommends the use of labor-based technology on public works (rural roads).

Works on roads and associated structures (bridges, culverts, drainage channels) can be implemented using small-scale contractors. Using the private sector to carry out this work will be a stimulus for strengthening and expanding the local small-scale contracting industry. Small-contractors can be equally instrumental in securing the short and long term employment gains from labor-based rural road works. The strategy suggests working with and through small-scale contractors and developing their skills to administer and implement labor-based works. This will contribute to the strengthening of the local construction industry. Small-scale contracting is an effective mechanism for works implementation and will be a focus of training activities to raise their skill levels and improve working conditions for labor.

There will be insufficient private sector capacity to implement the rehabilitation and reconstruction works. It is necessary to consider measures to strengthen the private sector capacity. It is important to identify the immediate training needs of small-scale contractors to involve them as soon as possible.

Local governments in disaster-affected areas are severely affected and need to be strengthened. Support to local governments to manage disaster response is one of the priorities that must be addressed. Such support will have two dimensions in terms of improving the rural road network. One of them is strengthening regional planning and coordination capacity of local governments. Second, strengthening the technical capacity of relevant local government staff to ensure implementation is carried out according to standards.

Following are the important factors during the rehabilitation and reconstruction of infrastructure. 1

| Num | Key Factors | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Coordination | Active participation in coordination efforts enables lead agencies to: - Establish clear division of labor and responsibility According to the agreed roles and mandates of the rehabilitation and (re)construction initiative, determine all the authorities and institutions that you will need to collaborate with, as well as the roles they will be playing in the implementation of the program. |

| 2. | Communication | Maintain effective communications channels with all key stakeholders (i.e., beneficiaries, partners, local authorities, donors, inter-agency level). Determine the most appropriate and effective way to communicate clearly, explain the purpose of an assessment, process and the extent to which assistance will be available. |

| 3. | Assessment | Draw up an inventory of existing infrastructure – nature and extent of damage caused – and assess the remaining capacity. |

Damage assessment | Carry out a preliminary assessment of reconstruction and resource requirements. | |

Needs assessment | Gender considerations should be kept in mind when analyzing capacities and needs of the disaster affected. Infrastructure planning, design and reconstruction must be coordinated with the plan for sheltering options to ensure the availability of basic services such as water, sanitation, solid waste management, health facilities and education. | |

Impact assessment | Identify likely impact of response in the short- and long-term. Ensure that the infrastructure is sustainable both from an economic and social (cultural and traditional) perspective. | |

Hazard assessment | Assess the frequency and dimension of all potential sources of natural hazards (geological, meteorological or hydrological) in the area. Ensure that infrastructure design is resilient to the most likely hazard scenario. Existing academic studies and hazard maps may provide information for the hazard evaluation. However, depending on the prevalent hazards and the site, it may also be necessary to conduct site-specific risk analysis. Local secondary disaster effects (e.g., landslides from excessive rain or ground shaking) should be anticipated and considered. | |

| 4. | Organizational capacities and operating modalities | Before determining “who will do what,” it is pertinent to analyze the capacity and mandate of the Host National Society, and Partner National Society. Contingent on the capacities identified, the Host National Society may decide to carry out uni-, bi-and/or multi-lateral projects. The uni-, bi- or multi-lateral projects may also involve working in collaboration with other aid organizations and/or government authorities. Once the operational modality has been decided upon, and terms and conditions negotiated, make sure that an agreement or a memorandum of understanding (MoU) covering all details is signed between the concerned parties. |

| 5. | Human resources | All staff must be knowledgeable of the local culture and traditions, local needs and experienced in the techniques (engineering) to be used in implementing the program. |

| 6. | Define roles and responsibilities | Define the roles and responsibilities of the personnel and organizations involved from the onset (i.e., in assessments; the design and siting of appropriate infrastructure; the enforcement of design; and the quality control of construction, operation and maintenance). Set up a system of consultation and collaboration with local engineers, contractors, consultants, government, local authorities and the affected community. |

| 7. | Information management system | Ensure there is a systematic electronic and hard copy filing and archiving system in place. |

| 8. | Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) | The memorandum of understanding (MoU) establishes a framework for collaboration between the key stakeholders by clearly expressing the common goals of the parties who are entering the memorandum of understanding (MoU). There may be an overall memorandum of understanding (MoU) for the entire program as well as more specific separate project memorandum of understanding (MoU). An memorandum of understanding (MoU) should clearly stipulate the following: - Details of the organizations being signatory to the memorandum of understanding (MoU) |

| 9. | Review legislation and good practices | Conform to national/local building codes. In the event that building codes do not exist, conduct research on existing codes of practice for hazard resistance, which might include the following: - Investigate the history of code development and level of hazard inclusion. Determine whether the building codes are adequate for use in infrastructure reconstruction. Familiarize with host government legislation to determine whether tenders can be opened for bids to international contractors including joint ventures. |

| 10. | Review of local construction capacity | Identify local construction practices for the relevant type of infrastructure. A rapid assessment may be made in the case of new construction. A more detailed analysis is required in a retrofitting project. Weaknesses in structures and in the vulnerability of infrastructure to the identified natural hazards must be assessed. This may include a study of the rate of degradation of the structure and its materials over time to assess resilience against projected hazards. Determine the strengths and durability of materials in existing or proposed infrastructure. Ensure that the relevant line ministries and/or local authorities can maintain the infrastructure in the long-run. Identify those who will carry out the design and construction – engineers, contractors, consultants and ensure they comply with codes. Assess program management and administration capacity and strengthen it with training or outside expertise. Assess local construction practices, their resistance to the determined hazards, and the level of risk this poses. |

| 11. | Site selection for construction of new infrastructure | When signing a separate project memorandum of understanding (MoU) ensure that the site has been identified prior to signing of the memorandum of understanding (MoU). The site for development will typically be defined by the local government based on availability, land-use plans, and economic criteria. Site selection will apply to construction of new infrastructure or replacement of an infrastructure that has been identified as being in a hazard zone, as per hazard assessment. If your assessment reveals that the site is not suitable, do not agree to reconstruct on the site. Share the findings with the government and renegotiate with them. |

| 12. | Disaster risk reduction (DRR) oriented rehabilitation and reconstruction | Create a project that focuses on reducing vulnerabilities and increasing capacities to make the affected community safer and more resilient. This is usually done through structural (physical construction to reduce potential impact) and/or non-structural (policies, public awareness, land-use planning, construction types) measures undertaken to minimize the adverse impact of potential hazards. |

| 13. | Environmentally friendly initiative | Local materials should be used as much as possible and so long as there are no adverse effects on the environment. Ensure that the program includes measures to mitigate any negative environmental impact of the infrastructure development especially in the long-term. |

| 14. | Design | Design a sustainable and socially acceptable strengthening or (re)construction solution that satisfies disaster risk reduction (DRR) objectives. Consider limitations of finance, construction skills and material availability. Identify an interim solution. Ensure that the environmental and social impacts of the proposed solution are acceptable. Adhere to local or national building codes. Apply the “build back safer” principle. In evaluating infrastructure technology options, evaluate the following: - Consider the financial and operational capacity of the entity responsible for service provision. |

| 15. | Government levied sales tax and import duties | There may be a need to import material and equipment. Negotiate value added tax (VAT) exemptions, deferments/waivers on purchases and payments to contractors/consultants. If value added tax (VAT) exemptions are not possible it is imperative to make provisions to be able to pay duty charges on imported goods. |

| 16. | Obtaining approval | Obtaining plan approvals can be a time consuming and tedious process. It is essential to obtain the necessary approvals from the authorities and where necessary by the line ministries. The program should support this process and liaise with relevant authorities to grant planning approval prior to commencement of construction. |

| 17. | Procurement and tendering | Follow the Procurement of Works and Services for Construction Projects guidelines for tendering and procurement procedures. Possible modalities of contractor engagement: - Working in partnership with the government |

| 18. | Consultants and contractors | Prior to selecting consultants or going to tender, it is advisable to research capacity available in-country following the disaster. Large-scale infrastructure projects require engagement of larger national or international firms, which may then need to import labor to complete the project. Check national legislation on whether it is permitted to bring in international firms or import labor from another county. - A report on recent projects carried out by the company Role of consultants - End-user to provide greater input The final design has to be signed off by the government. |

| 19. | Construction | The quality of post-disaster construction must not compromise the design intent. Establish procedures for multi-disciplinary inspection and check against specifications of works throughout the building process in the following ways: - Test materials and check adherence to design guidelines. |

| 20. | Final completion of works | Prepare in advance for contract finalization with contractors: - Built drawings |

| 21. | Maintenance and handover | It is crucial that the end-user, who is eventually going to be in charge of maintaining the infrastructure, is involved in reconstruction decisions and discussions. It is essential to ensure that the infrastructure that is being constructed is durable and can be maintained properly by the relevant authority after it is handed over. Ensure that the operator of the facility is made aware of the defects liability period (DLP). |

| 22. | Monitoring and evaluation | Assess the adequacy of the restored road infrastructure system and the success of the project as a whole. This assessment should include evaluation of: - Functionality, social acceptability and sustainability Lessons learned regarding strengthening hazard resilience should be summarized, shared, and drawn upon for future projects. |

In the pandemic situation, the use of the big data ecosystem is very necessary to monitor and detect natural hazards, reduce their effects, and contribute to the recovery and reconstruction process 1. The major data source for post-disaster recovery monitoring is remote sensing data, including satellite and aerial imagery. Based on changes recorded by multi-temporal remote sensing data, needs for reconstruction around damaged areas can be detected and monitored. The methodology of change detection is similar in comparison to damage assessment. The recovery workers operate within health protocols, such as social distancing, wearing masks, washing hands regularly, not gathering, and restricting movement. Previously, workers were tested before entering the work location; only those who were healthy could work in the field.

Recovery efforts require coordination at several levels of government and stakeholder institutions having specific responsibilities for central and state government, the private sector, volunteer organizations, and international aid agencies. The recovery measures last until all systems are back to normal or better. The success of recovery measures depends on four actors at once. First, the central government plays an important role in the disaster recovery phase. The central government has the authority to cooperate with stakeholders, and conduct and facilitate the collection and management of donated resources and volunteers. In addition, the central government is authorized to lead simultaneous coordination with a number of stakeholders to quickly resolve recovery problems, as well as to provide resources based on need and within its capabilities, according to norms. Second, state and local governments are responsible for damage assessment and all the phases of recovery and reconstruction (short- to long-term). In addition, some of the state and local government tasks are to lead and support need and damage assessment operations, provide relevant data regarding the severity of the disaster and assessment of individual needs, participate in and support public information and education programs regarding recovery efforts and available central/state government assistance, and coordinate with the central government and other stakeholders for reconstruction management. Third, the private sector must be involved in disaster management and businesses must integrate disaster risk into their management practices. There is a need to involve the private sector in the areas of technical support, reconstruction efforts, risk management (including covering risks to their own assets), financial support of reconstruction efforts, and risk-informed investments in recovery efforts. Fourth, voluntary organizations and international aid agencies may participate in the activities regarding need and damage assessment and supporting government efforts in reconstruction, especially insofar as the mandate requires them. 2

1 Disaster Management Module. 2017. Ministry if Public Works and Housing. Indonesia.

2 Widjoyono, T., et al. 2019. Disaster and Risk Management Toward Resilient Road Infrastructure in Indonesia. World Road Congress. Abu Dhabi.

1 International Labor Organization. A Strategy for the Rehabilitation of the Rural Transport System in Tsunami-affected areas. (ilo.org)

1 International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.2012.Geneva. Post-Disaster Community Infrastructure Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Guidelines.pdf (sheltercluster.org)

1 Manzhu Yu, Chaowei Yang, and Yun Li. 2018. Big Data in Natural Disaster Management: A Review. Geosciences, 8, 165.

2 National Disaster Management Plan India. 2016. National Disaster Management Authority. India. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/National%20Disaster%20Managem...

The scope of this section is to present worldwide considerations regarding the uncommon disasters: large-scale and combined disasters. We distinguish these types of disasters from common disasters by employing the term “disaster” for such cases. A brief worldwide overview of major combined and large-scale disasters follows the definition overview.

This chapter is relevant to issue Disaster Management for Combined and Large Disasters. The definition of what constitutes a large and/or combined disaster varies. Therefore, the scope of this chapter is to provide an overview of the existing definitions for combined and large disasters followed by experiences and lessons learned from disaster occurrence in terms of coordination of the authorities responsible for disaster response and the risk/disaster management techniques applied to minimize the consequences of their impact.

There exist several definitions for large-scale disasters. The ones provided next are among the most prevalent and commonly used:

OECD defines as being of large-scale any serious disaster which:

According to the above, a major disaster is a catastrophic, high-consequence event which:

Indicators of capacity overload include the following:

| Category | Disaster characterization | Number of casualties or size of area impacted |

|---|---|---|

Scope I | Small | <10 persons or <1 km2 |

Scope II | Medium | 10–100 persons or 1–10 km2 |

Scope III | Large | 100–1,000 persons or 10–100 km2 |

Scope IV | Enormous | 1000–10,000 persons or 100–1,000 km2 |

Scope V | Extraordinary (Gargantuan) | >10,000 persons or >1,000 km2 |

Generally speaking, such large-scale disasters will have an impact comparable to that of an earthquake of intensity/magnitude at least 7.0 on the Richter scale and it will usually cause:

The aforementioned impacts are subject to the following specifications:

Therefore, for a disaster to be characterized as being of large-scale it must meet any two of the following conditions:

Table 5.2.1.1.2 summarizes qualitatively the main characteristics of large-scale disasters, as these pertain to the aforementioned definitions for the purposes of this report.

| Main characteristics | Disaster mode | Occurence | Scale of single disaster | Disaster status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Uncommon | Single | Very rare | Medium | Does not change |

Large scale | Rare | Large |

Table 5.2.1.1.3 provides a summary of major single-mode disaster, which occurred in the 1989-2013 period with their respective impacts.

| Year | Disaster Name | Intensity (Richter) | Death Toll (persons approx.) | Affected Area (103km2) | Economic Losses (billion $) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1995 | Kobe Earthquake Disaster in Japan | 7.3 | 6,434 | Approx. 120 | 86 |

1998 | Yangtze River Basin Flood in China | - | 1,562 | 223 | 13 |

2003 | SARS in China | - | 336 | Approx. 500 | 25 |

2003 | European Heat Wave | - | 37,451 | Approx. 100 | 16 |

2004 | Indian Ocean Earthquake – Tsunami Disaster | 8.9 | 230,210 and 45,752 missing | 800 x 5 km coastal line seriously damaged | Approx. 0.9

|

2005 | Kashmir Earthquake in South Asia | 7.6 | 80,000 | Approx. 20 | Approx. 4.2

|

2008 | Burma Hurricane Disaster | - | 78,000 and 56,000 missing | Approx. 20 | Approx. 3.4

|

2008 | Freezing Rain & Snow Disaster in Southern China | - | 129 and 4 missing | Approx. 100 | 18.2 |

2008 | Wenchuan Earthquake Disaster in China | 8.0 | 69,227 and 17,923 missing | Approx. 50 | Approx. 150 |

2010 | Haiti earthquake | 7.0 | 112,250 | NA | 8 |

2010 | Chile earthquake | 8.8 | 215 | 0.6 | 66.7 |

Many populated areas are affected by a wide variety of disasters, such as earthquakes, landslides, tsunamis, flooding, volcanic eruptions, heavy rains, wildfires, etc. Many analyses of disasters take a single-mode approach, which treats disasters as being separate and independent. In many cases, however, the temporal and spatial distributions of these disasters overlap and there can exist interaction relationships between disaster types.

A combined disaster could be defined as a temporal and spatial coincidence of two or more at least medium-scale independent disasters whose consequences do not change in time, resulting in an impact greater than what we would obtain by considering separately the impacts of each disaster independently and summing these up 1. Figure 5.2.1.2 provides a pictorial representation for simultaneous occurring disasters.

Figure 5.2.1.1 – Representation of simultaneous occurring disasters

A combined disaster could also be defined as the consecutive occurrence of one at least medium-scale disaster triggering one or more secondary disasters, thus forming a chain reaction (cascade/domino effect), which acts synergistically, and results in a greater catastrophe than what would be expected by a single-mode disaster. In such case we consider the status of the disaster to change in time.

In the evaluation of the aftermath of a combined disaster the approach should be differentiated between a situation where a primary disaster triggers secondary disaster(s) (e.g. a flood triggering a landslide) and a situation where that primary disaster increases the possibility of secondary disasters occurring. The occurrence of a given disaster may not only cause additional events via cascade or domino effects, such as earthquakes triggering tsunamis, or volcanic eruptions triggering earthquakes, but the initial event may also increase the vulnerability of the region to disasters in the future. An example of this would be a case of an earthquake, which would damage a flood defense structure like a dam.

There is also a direct relationship between the intensity or magnitude of the primary disaster and the intensity of the secondary disaster(s) which may amplify the total impact.

Table 5.2.1.2.1 summarizes qualitatively the main characteristics of combined disasters, as these pertain to the aforementioned definitions for the purposes of this report.

| Main characteristics | Disaster mode | Occurence | Scale of single disaster | Disaster status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Simultaneously occurring | Multiple | Simultaneous | Medium | Does not change |

Chain-reaction | Consecutive | Medium | Changes with time |

Table 5.2.1.2.2 provides a summary of major combined disasters, which occurred in the 2005-2013 period with their respective impacts.

| Year | Disaster Name | Intensity (Richter) | Death Toll (persons approx.) | Affected Area (103km2) | Economic Losses (billion $) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2005 | Hurricane Katrina in USA | - | 1,836 pers. dead | 40 | 105 |

2011 | Flood in Thailand | - | 815 pers. dead | 20 | 45.7 |

2011 | East Japan earthquake and tsunami | 9.0 | 15,870 pers. dead 2,814 pers. missing | 561 | 200 |

From the viewpoint of disasters and the disaster management cycle, as shown in Figure 5.2.1.3.1, we can define a situation as being well managed when the management cycle evolves smoothly.

Figure 5.2.1.3.1 – Disater management cycle

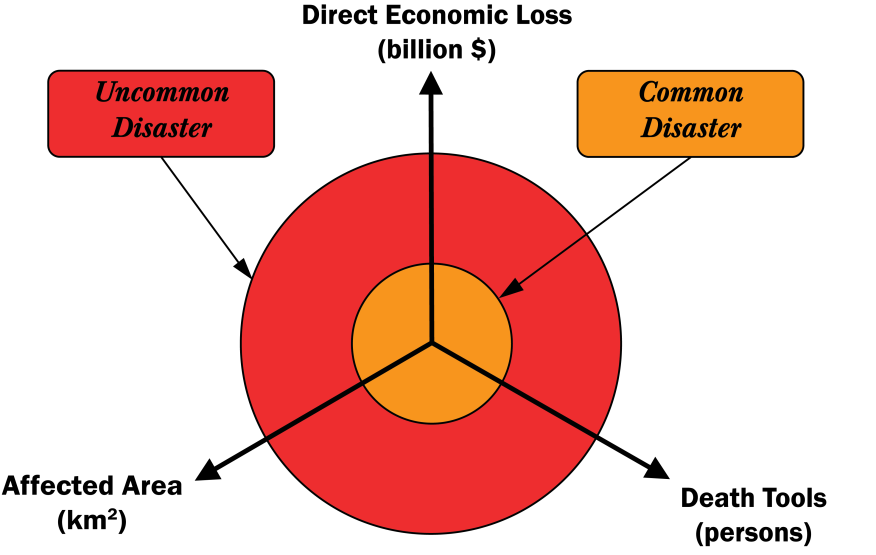

In case of combined and large-scale disasters, the management cycle does not suffice to properly characterize the situation. Combined and large-scale disasters can be recognized as the situation in which the disaster level is large and complicated, the vulnerability of the potentially affected area is high, and the capacity of the potentially affected area is not enough. Figure 5.2.1.3.2 portrays the differences between common and uncommon disasters.

Figure 5.2.1.3.2 - Difference between common and uncommon disasters

According to the definition provided by Quarentelly in 1985, “Disaster is a crisis situation that far exceeds the capabilities”.

In case of uncommon disasters, the potentially affected area has less capacity to handle it and is more vulnerable against the uncommon disaster; therefore, the potential consequences are usually great. In case of uncommon disasters, the disaster level is large and so is the disaster. In case of simultaneous occurring disasters, the capacity is not enough to resist against these. Chain-reaction disasters involve situations where the multiple disasters occur consecutively; therefore, the capacity does not suffice to resist against the disasters.

This chapter present the major experiences in the world, best practices and lesson learned from large scale and combined disasters.

In order to analyze the weaknesses in disaster management that were realized from combined and large-scale disasters, an international survey was conducted to countries that suffered from major disasters. Table 5.2.1.4.1.1 provides the details of the international survey.

| Survey items | Description |

|---|---|

| Survey date | From May 2013 to May 2014 |

| Survey countries | Member countries of PIARC TC1.5 The countries that suffered from recent well-known major hazard |

| Survey form | Character of the disaster Major difficulty in disaster management ITS application in disaster management Review and lessons in terms of the key-words below Robustness Self-sustainedness Dynamic risk management |

Thirteen case studies were collected through the survey. Table 5.2.1.4.1.2 provides a list of these.

| Disaster | Reporter |

|---|---|---|

1 | [Large scale disaster –Large-] 1994 Northridge Earthquake, USA | Herby LISSADE Chief, Office of emergency Caltrans, USA |

2 | [Large scale disaster –Large-] 1995 Kobe Earthquake, Japan | Yukio ADACHI Chief maintenance engineer, Hanshin expressway, JAPAN |

3 | [Combined disaster -Simultaneous & Chain-] 2005 Hurricane Katrina, USA | James LAMBERT Professor University of Virginia, USA |

4 | [Large scale disaster –Large-] 2007 Tabasco flood, Mexico | Gustavo MORENO President, SESPEC MEXICO |

5 | [Combined disaster - Simultaneous -] 2009 Taiwan heavy rain, Taiwan | Chin-Fa, CHEN Directorate General of Highways MOTC, Taiwan |

6 | [Large scale disaster -Uncommon-] 2010 Eruption of Volcano Merapi, Indonesia | Djoko MURJANTO Director general of highways MOI, Indonesia |

7 | [Large scale disaster -Uncommon-] 2010 Chemical Spill, Hungary | Csilla KAMARAS Engineer National Transport Authority, Hungary |

8

| [Large scale disaster -Large-] 2010 Romania flood, Romania | Constantin ZBARNEA Regional Division of Roads and Bridges Iasi ROMANIA |

9 | [Combined disaster - Simultaneous -] 2011 East Japan earthquake, Japan | Yukio ADACHI Chief maintenance engineer, Hanshin expressway, JAPAN |

10 | [Large scale disaster –Large-] 2011 Kii Peninsula Heavy Rain, Japan | Yukio ADACHI Chief maintenance engineer, Hanshin expressway, JAPAN |

11

| [Large scale disaster -Uncommon-] 2012 Cameroon flood, Cameroon | Francis NDOUMBA MOUELLE Kizito NGOA Cameroon |

12 | [Large scale disaster -Large-] 2012 Waioeka Gorge Slip, New Zealand | Brett GLIDDON State Highway Manager New Zealand Transport Agency, New Zealand |

13 | [Large scale disaster -Large-] 2013 Queensland flood, Australia | Andrew EXCELL Regional Manager MeTRO, DPTI, Australia |

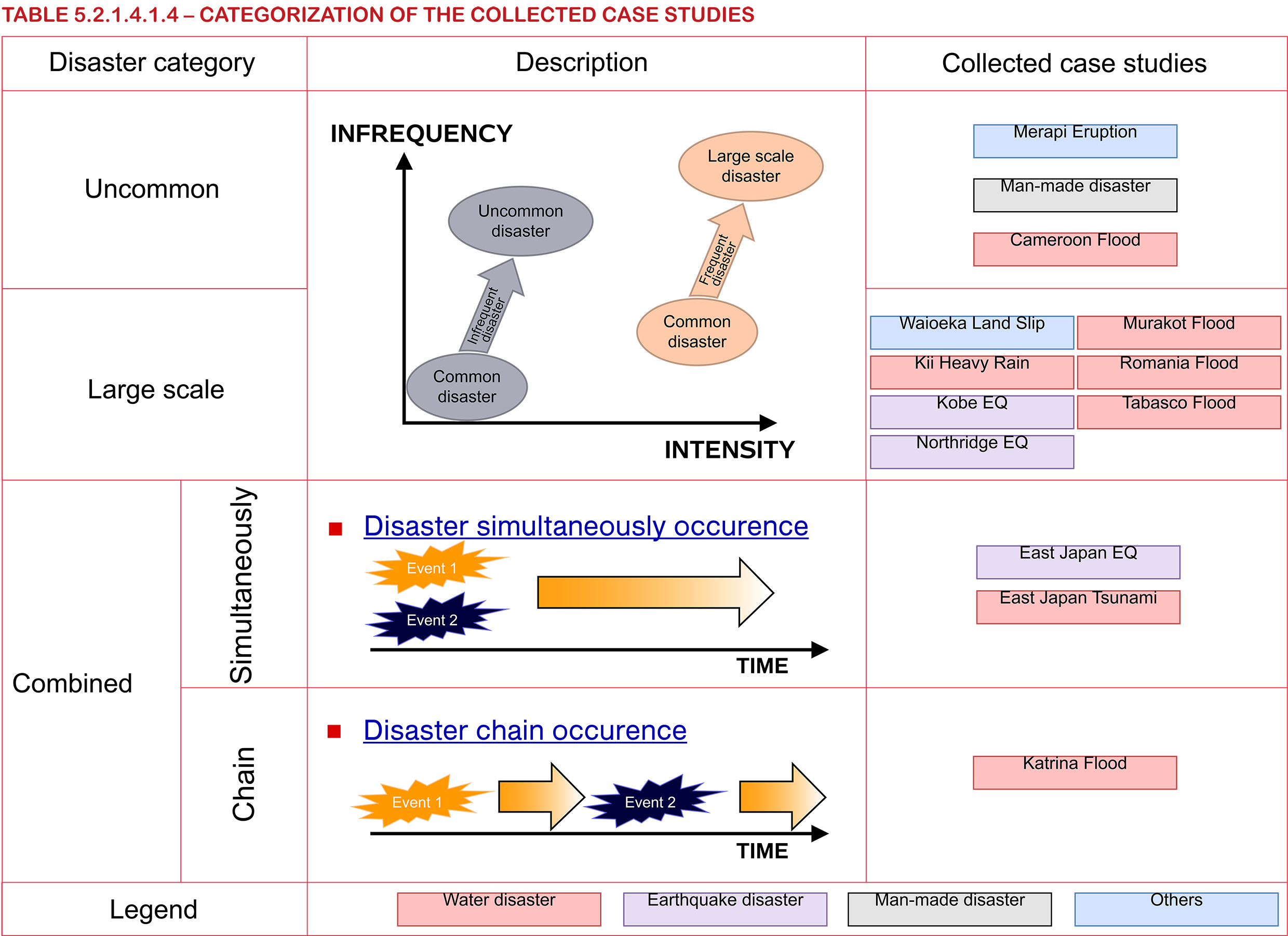

The collected experiences were categorized into uncommon disaster, large-scale disaster, simultaneously occurring disaster, and chain reaction disasters based on their mode, frequency of occurrence, scale, and status (see Table 5.2.1.4.1.3).

| Main characteristics | Disaster mode | Ocurrence | Scale of single disaster | Disaster status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Large scale disasters | Uncommon | Single | Very rare | Medium | Does not change | |

Large scale | Rare | Large | ||||

Combined disasters | Simultaneously ocurring | Multiple | Simultaneous | Simultaneous | Does not change | |

Chain-reaction | Multiple | Consecutive | Consecutive | Changes with time | ||

Table 5.2.1.4.1.4 provides a description for the aforementioned categorizations and the collected case studies for each.

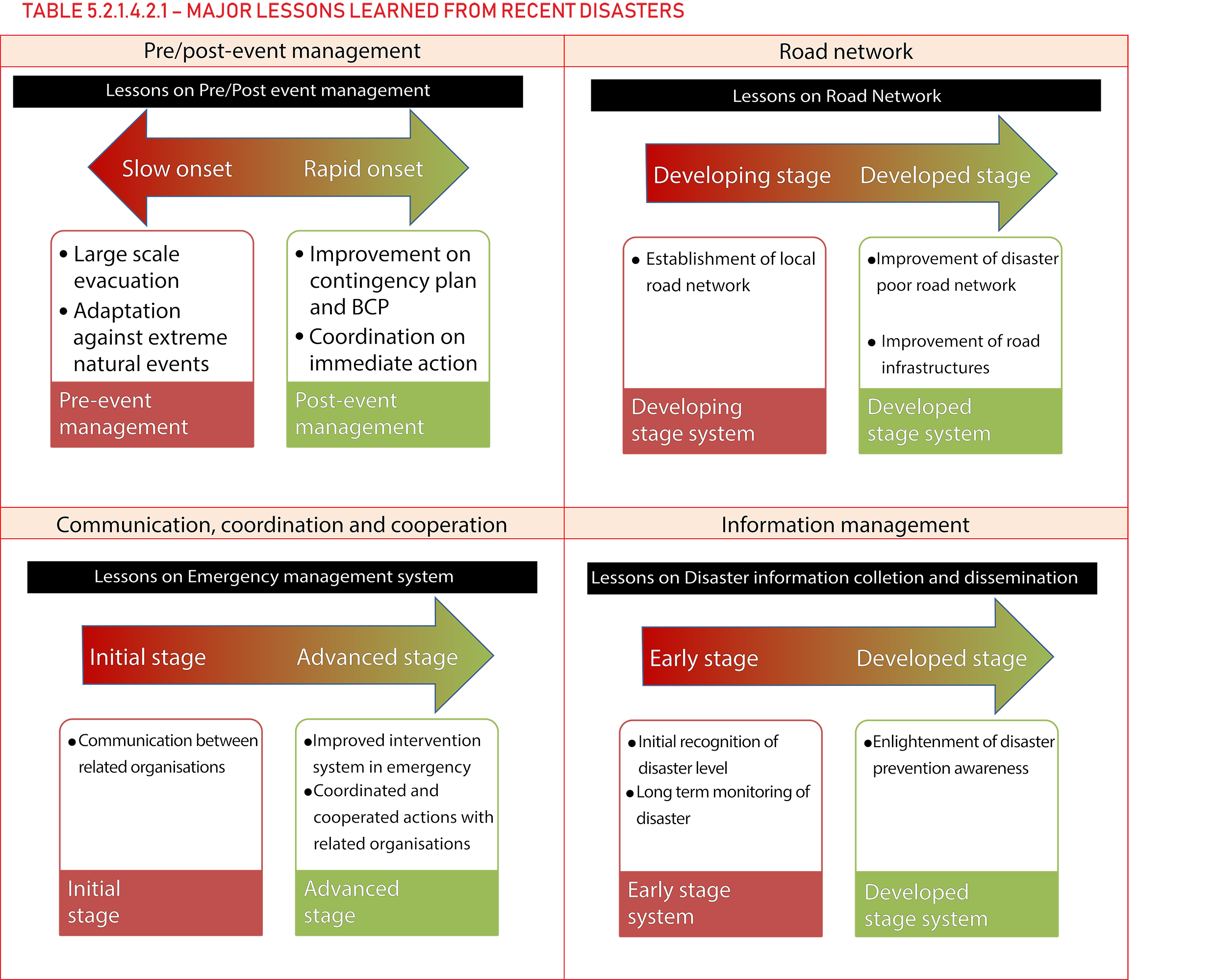

Major lessons collected from recent disaster experiences can be classified into four fields: Pre/post event management, road network, communication-coordination-cooperation, and information management, as shown in figure 5.2.1.4.2.1 – Field classification of case studies from International survey.

Figure 5.2.1.4.2.1 – Field classification of case studies from International survey

Depending on the preparedness of the affected sites, differences in disaster management are observed in each field.

There are two major hazard modes. One mode consists of slow-onset hazards such as floods, tropical storms, snow, etc., while the other mode consists of rapid-onset hazards such as earthquakes. The learned lessons are quite different between these modes. Lessons learned from slow-onset disasters are related to pre-event activities aiming to reduce or mitigate the disaster.

The most important lesson derived from the 2005 Hurricane Katrina in USA, was that there had been no preparation for mass evacuation. Mass evacuation requires coordination of several different field organizations and communication between road administrators and evacuees. Mass evacuation strategy has since been studied by FHWA and included in several references. Mass evacuation is approached from an evacuation management angle rather than traffic management.

The case of the 2007 Tabasco heavy rain event in Mexico was considered the result of the slowest onset disaster caused by climate change effects. Some engineers pointed out that this event should serve as a trigger for studies such as “Development of adaptation strategy against extreme events” and “Study on climate change effects to infrastructures”.

A redundant road network is necessary for disaster management. The derived lessons related to road network are also different between the network development levels. The major lesson is that construction of a redundant road network should be considered when designing and developing the network. For networks already under operation, major lessons derived are related to the quality of the road infrastructure (e.g. reliability and resistive infrastructure) and the standards of the road network.

In the case of the 2000 chemical spill in Hungary, the sole lifeline road was closed due to the spilled sludge for a long time. This road closure, combined with poor infrastructure of the road network, resulted in extreme difficulties in the transportation of logistics due to limited access of freight traffic to the disaster area.

In the case of the 2011 East Japan earthquake, areas hit by the tsunami were isolated due to the loss of a major road network caused by the tsunami and due to damage to local roads caused by the earthquake. High quality road network projects from now on take disaster resilience into consideration for the project cost-benefit analysis [4.2.4].

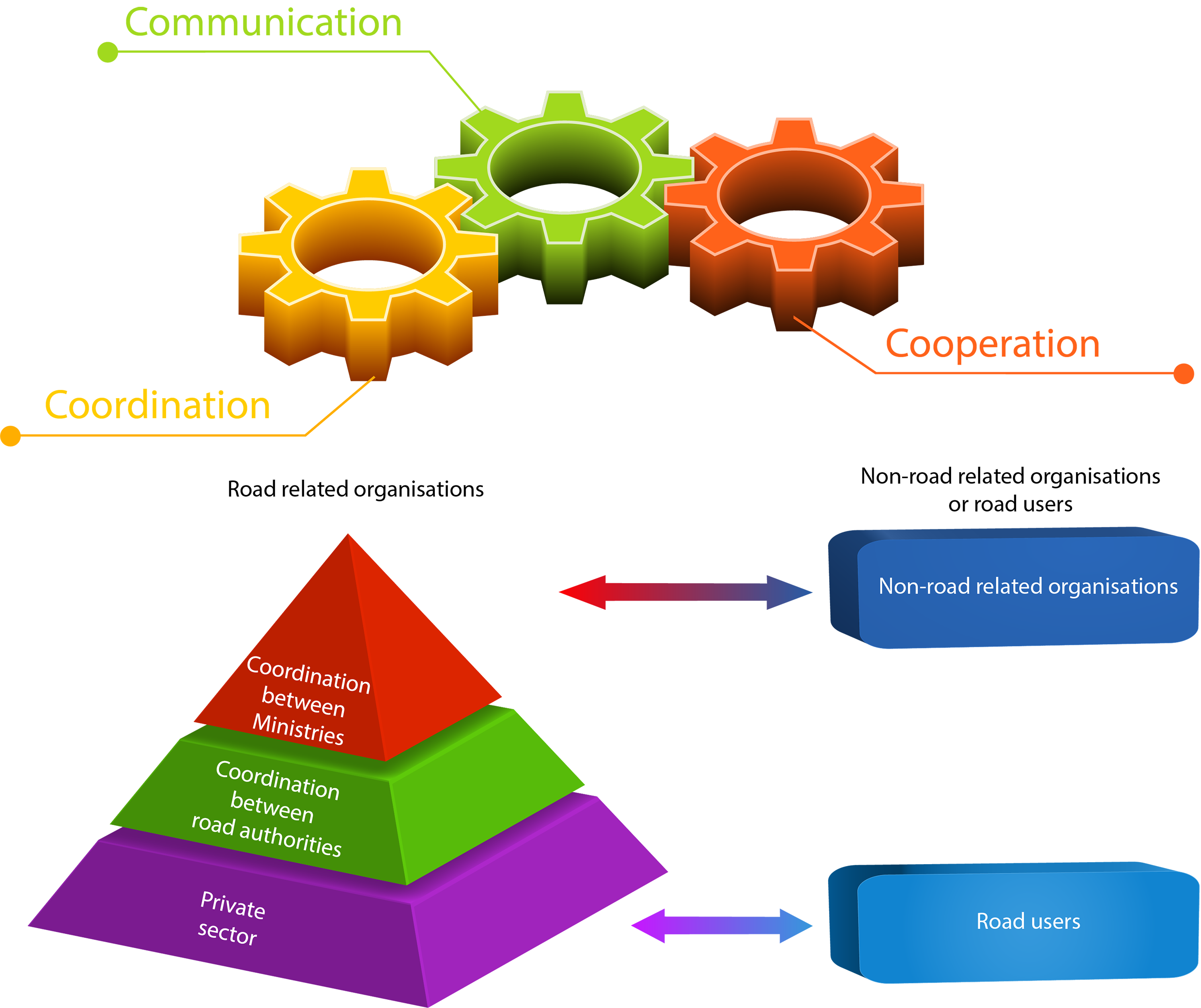

Coordination is very important in managing disasters. Coordination depends on the preparedness of the road authority, related organizations, and society. Coordination work is a process that can be enhanced by good communication among related organizations and road users, and coordination and cooperation between road and non-road related organizations, as shown in Figure 5.2.1.4.2.2.

Figure 5.2.1.4.2.2 – Communication development process and coordination pyramid

According to the experience of the 2010 Merapi volcano eruption in Indonesia, the major lesson was the limited communication and coordination between related disaster management organizations, which resulted in poor quality of the disaster work. Communication is the first step in coordination.

Advance preparedness in coordination is to make cooperative agreements with related organizations prior to the upcoming event. According to the lessons derived from disaster experiences in Japan, most road authorities prepare such cooperative agreements not only with construction contractors and consultant companies, but also with non-road related organizations [4.2.5].

Disaster information management is very important for managing disasters. Disaster information management includes:

Lessons regarding inadequate acquisition of disaster information can also be derived from the case of the 1995 Kobe earthquake in Japan, where recognition of damage level and area in the road network was very difficult; conventional communication tools were not available because of the disaster.

Similar lessons were derived from the 2011 East Japan earthquake, where electricity-based communication and information tools were inactive because of power shutdowns due to the strong earthquake and the tsunami that followed. In the case of the 2011 Kii peninsula heavy rain in Japan, long term hazard monitoring was needed to prevent secondary disasters.

An interesting and important lesson was derived from the 2009 Morakot heavy rain in Taiwan. Even though the most advanced early warning system throughout the country was in place, public awareness was limited. This resulted in improper activation of the preparedness action that was supposed to follow based on the message delivered by the warning system. As a result, the Taiwanese government acted to further promote public disaster awareness. ITS technologies are important disaster management tools for information management and for raising public awareness.

The derived lessons from each field are summarized in Table 5.2.1.4.2.1

The coordination pyramid including road related organizations and non-road related organizations is shown in Figure 5.2.1.4.3. Within the road-related organizations, efforts have been made for communication and coordination. Coordination is a fundamental process in disaster management and should be enhanced within road-related organizations in order to mitigate further damages due to the disaster.

According to the report regarding the 1995 Northridge earthquake in USA, an advanced approach coordination center was established shortly after the earthquake. This center controls coordinative actions under the power of the state government.

Other advanced approaches to improve coordination have been introduced by Japan. According to these, liaison engineers and task-force engineers are sent to the disaster area in order to promote coordinated restoration actions between national and local governments. This system not only promotes coordinated action but also supports engineering issues to be solved in disasters.

The most advanced preparedness actions are being introduced in Japan. According to the lessons derived from the 2011 East Japan Earthquake, some road authorities are trying to implement mutual cooperative action not only within road related organizations but also with non-road related organizations. This involves making agreements in advance and periodical disaster exercises and drills are carried out among the agreement organizations. The agreements are usually made between national and local governments, road authorities, construction contractors, and consultant companies. The report of the 2011 East Japan earthquake outlines that quick inspection and restoration work could be initiated because of these mutual agreements. Mutual agreements with non-road related organizations such as mass media and NPOs are needed as preparedness actions for future events.

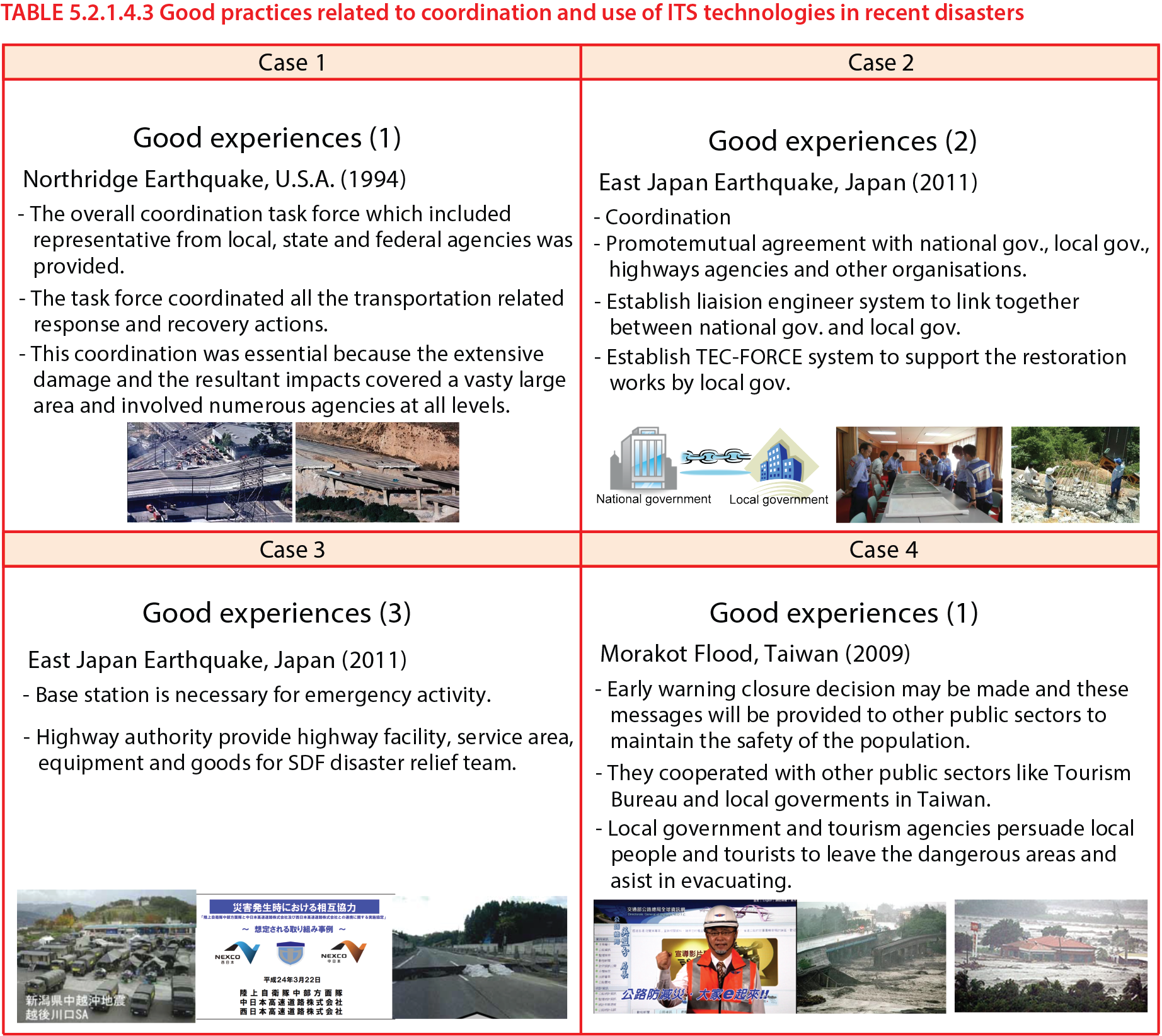

Currently, ITS technology is highly developed and it is being applied to improve traffic and safety management. Risk and disaster management are no exception.

An advanced application in the field of disaster management was reported in 2013 in Australia. The flood prediction and road closure possibility information were provided by VMS. The driver survey revealed that information dissemination using ITS technology was very effective for route selection. The continuous challenge for application of ITS technology in risk and disaster management is a continuous challenge and further research is needed in this field.

Case studies from the international survey that identify some good system developments to improve coordination and use of ITS technologies are shown in Table 5.2.1.4.3.

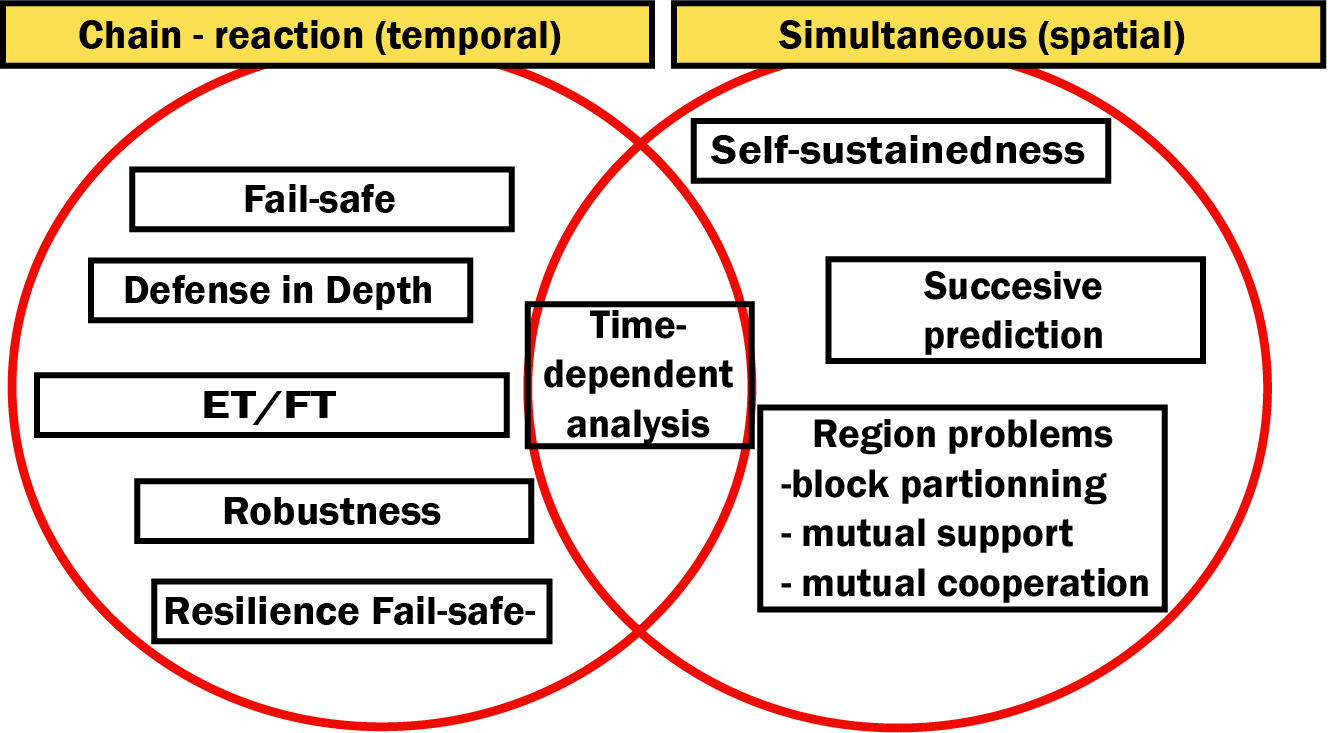

According to the lessons derived from the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident, a new concept for managing disasters in nuclear engineering was proposed.

The report indicated that the notable characteristics of the nuclear power plant event, which occurred because of the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake, were that: a) a very wide area was affected, and b) the disaster was compounded by a huge tsunami; therefore, no disaster assistance could be expected from the wider area which was also affected.

The report also indicated that the fatal event at the nuclear power plant was actually a series of separate serious events which occurred in a chain manner. This rendered the nature of the risk time-dependent. As addressing the situation involved both human actions and time-variable hazards, the most appropriate actions to be taken did not remain the same as time progressed to prevent the worst scenario for each elemental risk.

From the aforementioned features, Takada proposed the risk concept be extended so as to incorporate simultaneous failures and time-dependency in risk evolution. For this, the new concept “Safety Burst” was proposed in the report as follows:

Safety burst indicates the physical state that after either a single failure of a part or simultaneous failure of portions of a big complex engineering system with possible large failure consequence is initiated, further damage is propagating and extending and finally the expected performance of the system becomes out of control.

Many key words were introduced for improving management in two major Safety Burst situations -chain reaction-type situations and simultaneous-type failures as shown in Figure 5.2.1.4.3.

Figure 5.2.1.4.3 Key Words Introduced in Chain-Reaction and Simultaneous Type of Disasters

Among these key words, the ones indicated below and are considered very important.

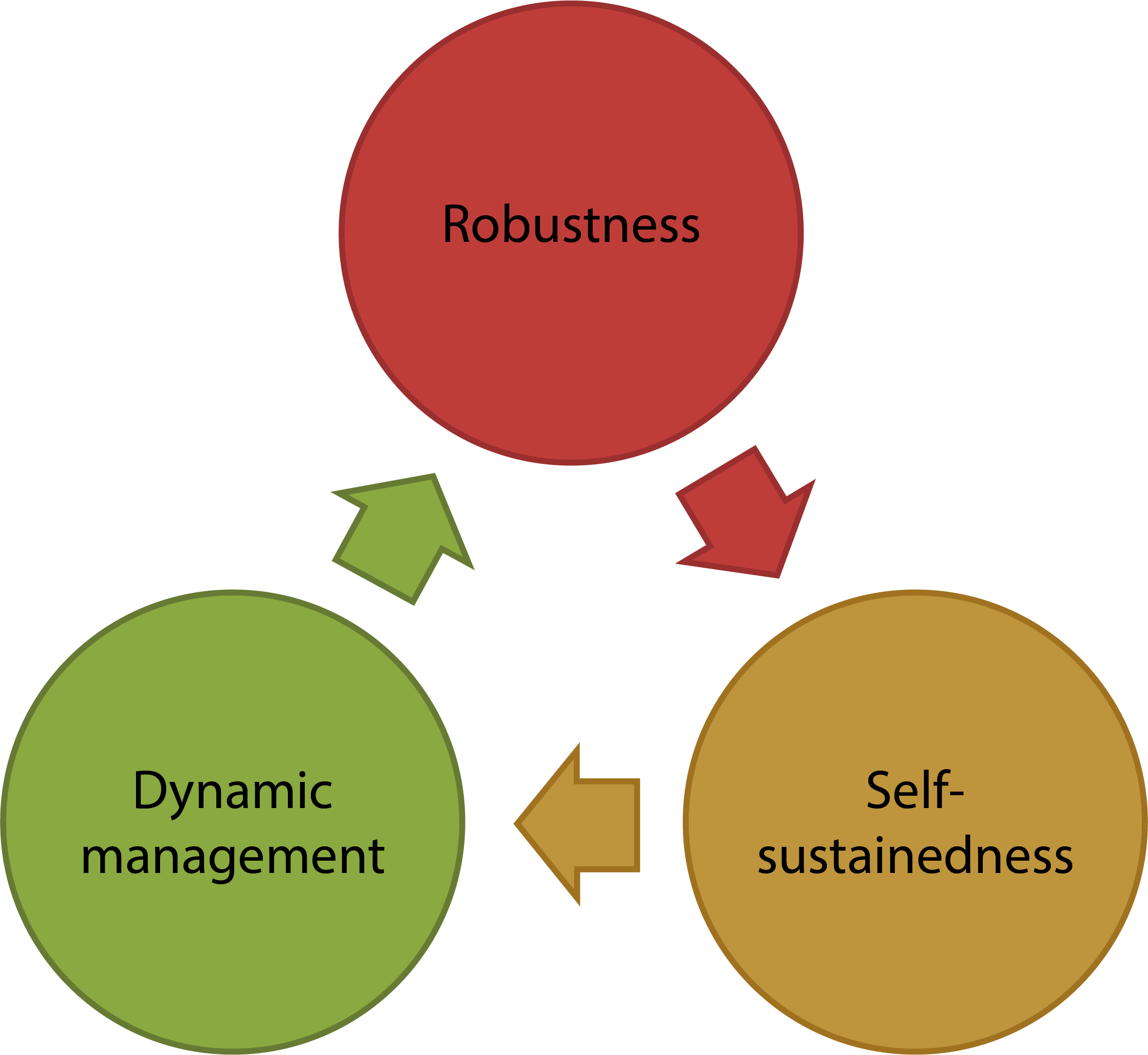

From the international study, it can be inferred that the world has experienced several large and combined disasters compared to previous decades. Preparing for such disasters is one of the actual urgent needs in terms of disaster management.

Based on the study’s findings, the properties of large-scale and combined disasters can be defined using the following characteristics:

For managing those disasters in the road network, preparedness should be up to date and new concepts are needed. These concepts should take into account the important key words identified in major Safety Burst situations: robustness, self-sustainment and dynamic risk management (see Figure 5.2.2).

Figure 5.2.2 – Important key words for managing road emergency situations

Based on the findings of the international survey, no differences could be found in preparedness for large and combined hazards from that assumed for common-scale disasters. However, a new concept for disaster management considering the Safety Burst condition is emerging after the 2011 combined and serious nuclear plant disaster that occurred in Japan. The road system and network should be well prepared against safety burst situations in which damages are propagating in space and expanding in time often resulting that the expected performance of the system becomes out of control. The recommendations considering such conditions are proposed as follows:

1 Ma Zhongjin - "Recommendations on China’s regional disaster mitigation. Disaster Reduction in China" article from China National Report On International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction, 1999

2 Mohamed Gad-el-Hak - “LARGE-SCALE DISASTERS - Prediction, Control, and Mitigation”. book printed by New York, Cambridge University Press, 2008

3 Peijun Shi, Carlo Jaeger, Qian Ye - "Integrated Risk Governance. Science Plan and Case Studies of Large-scale Disasters" book printed by Beijing Normal University Press, 2012

1 MATRIX MATRIX results II and Reference Report/Deliverable D8.5- New Multi-Hazard and Multi-Risk Assessment Methods for Europe - Risk governance and the communication process from science to policy: Evaluating perceptions of stakeholders from practice in multi-hazard and multi-risk decision support models - N. Komendantova, R. Mrzyglocki, A. Mignan, B. Khazai, F. Wenzel, A. Patt, K. Fleming