The scope of this section is to present worldwide considerations regarding the uncommon disasters: large-scale and combined disasters. We distinguish these types of disasters from common disasters by employing the term “disaster” for such cases. A brief worldwide overview of major combined and large-scale disasters follows the definition overview.

This chapter is relevant to issue Disaster Management for Combined and Large Disasters. The definition of what constitutes a large and/or combined disaster varies. Therefore, the scope of this chapter is to provide an overview of the existing definitions for combined and large disasters followed by experiences and lessons learned from disaster occurrence in terms of coordination of the authorities responsible for disaster response and the risk/disaster management techniques applied to minimize the consequences of their impact.

There exist several definitions for large-scale disasters. The ones provided next are among the most prevalent and commonly used:

OECD defines as being of large-scale any serious disaster which:

According to the above, a major disaster is a catastrophic, high-consequence event which:

Indicators of capacity overload include the following:

| Category | Disaster characterization | Number of casualties or size of area impacted |

|---|---|---|

Scope I | Small | <10 persons or <1 km2 |

Scope II | Medium | 10–100 persons or 1–10 km2 |

Scope III | Large | 100–1,000 persons or 10–100 km2 |

Scope IV | Enormous | 1000–10,000 persons or 100–1,000 km2 |

Scope V | Extraordinary (Gargantuan) | >10,000 persons or >1,000 km2 |

Generally speaking, such large-scale disasters will have an impact comparable to that of an earthquake of intensity/magnitude at least 7.0 on the Richter scale and it will usually cause:

The aforementioned impacts are subject to the following specifications:

Therefore, for a disaster to be characterized as being of large-scale it must meet any two of the following conditions:

Table 5.2.1.1.2 summarizes qualitatively the main characteristics of large-scale disasters, as these pertain to the aforementioned definitions for the purposes of this report.

| Main characteristics | Disaster mode | Occurence | Scale of single disaster | Disaster status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Uncommon | Single | Very rare | Medium | Does not change |

Large scale | Rare | Large |

Table 5.2.1.1.3 provides a summary of major single-mode disaster, which occurred in the 1989-2013 period with their respective impacts.

| Year | Disaster Name | Intensity (Richter) | Death Toll (persons approx.) | Affected Area (103km2) | Economic Losses (billion $) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1995 | Kobe Earthquake Disaster in Japan | 7.3 | 6,434 | Approx. 120 | 86 |

1998 | Yangtze River Basin Flood in China | - | 1,562 | 223 | 13 |

2003 | SARS in China | - | 336 | Approx. 500 | 25 |

2003 | European Heat Wave | - | 37,451 | Approx. 100 | 16 |

2004 | Indian Ocean Earthquake – Tsunami Disaster | 8.9 | 230,210 and 45,752 missing | 800 x 5 km coastal line seriously damaged | Approx. 0.9

|

2005 | Kashmir Earthquake in South Asia | 7.6 | 80,000 | Approx. 20 | Approx. 4.2

|

2008 | Burma Hurricane Disaster | - | 78,000 and 56,000 missing | Approx. 20 | Approx. 3.4

|

2008 | Freezing Rain & Snow Disaster in Southern China | - | 129 and 4 missing | Approx. 100 | 18.2 |

2008 | Wenchuan Earthquake Disaster in China | 8.0 | 69,227 and 17,923 missing | Approx. 50 | Approx. 150 |

2010 | Haiti earthquake | 7.0 | 112,250 | NA | 8 |

2010 | Chile earthquake | 8.8 | 215 | 0.6 | 66.7 |

Many populated areas are affected by a wide variety of disasters, such as earthquakes, landslides, tsunamis, flooding, volcanic eruptions, heavy rains, wildfires, etc. Many analyses of disasters take a single-mode approach, which treats disasters as being separate and independent. In many cases, however, the temporal and spatial distributions of these disasters overlap and there can exist interaction relationships between disaster types.

A combined disaster could be defined as a temporal and spatial coincidence of two or more at least medium-scale independent disasters whose consequences do not change in time, resulting in an impact greater than what we would obtain by considering separately the impacts of each disaster independently and summing these up 1. Figure 5.2.1.2 provides a pictorial representation for simultaneous occurring disasters.

Figure 5.2.1.1 – Representation of simultaneous occurring disasters

A combined disaster could also be defined as the consecutive occurrence of one at least medium-scale disaster triggering one or more secondary disasters, thus forming a chain reaction (cascade/domino effect), which acts synergistically, and results in a greater catastrophe than what would be expected by a single-mode disaster. In such case we consider the status of the disaster to change in time.

In the evaluation of the aftermath of a combined disaster the approach should be differentiated between a situation where a primary disaster triggers secondary disaster(s) (e.g. a flood triggering a landslide) and a situation where that primary disaster increases the possibility of secondary disasters occurring. The occurrence of a given disaster may not only cause additional events via cascade or domino effects, such as earthquakes triggering tsunamis, or volcanic eruptions triggering earthquakes, but the initial event may also increase the vulnerability of the region to disasters in the future. An example of this would be a case of an earthquake, which would damage a flood defense structure like a dam.

There is also a direct relationship between the intensity or magnitude of the primary disaster and the intensity of the secondary disaster(s) which may amplify the total impact.

Table 5.2.1.2.1 summarizes qualitatively the main characteristics of combined disasters, as these pertain to the aforementioned definitions for the purposes of this report.

| Main characteristics | Disaster mode | Occurence | Scale of single disaster | Disaster status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Simultaneously occurring | Multiple | Simultaneous | Medium | Does not change |

Chain-reaction | Consecutive | Medium | Changes with time |

Table 5.2.1.2.2 provides a summary of major combined disasters, which occurred in the 2005-2013 period with their respective impacts.

| Year | Disaster Name | Intensity (Richter) | Death Toll (persons approx.) | Affected Area (103km2) | Economic Losses (billion $) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2005 | Hurricane Katrina in USA | - | 1,836 pers. dead | 40 | 105 |

2011 | Flood in Thailand | - | 815 pers. dead | 20 | 45.7 |

2011 | East Japan earthquake and tsunami | 9.0 | 15,870 pers. dead 2,814 pers. missing | 561 | 200 |

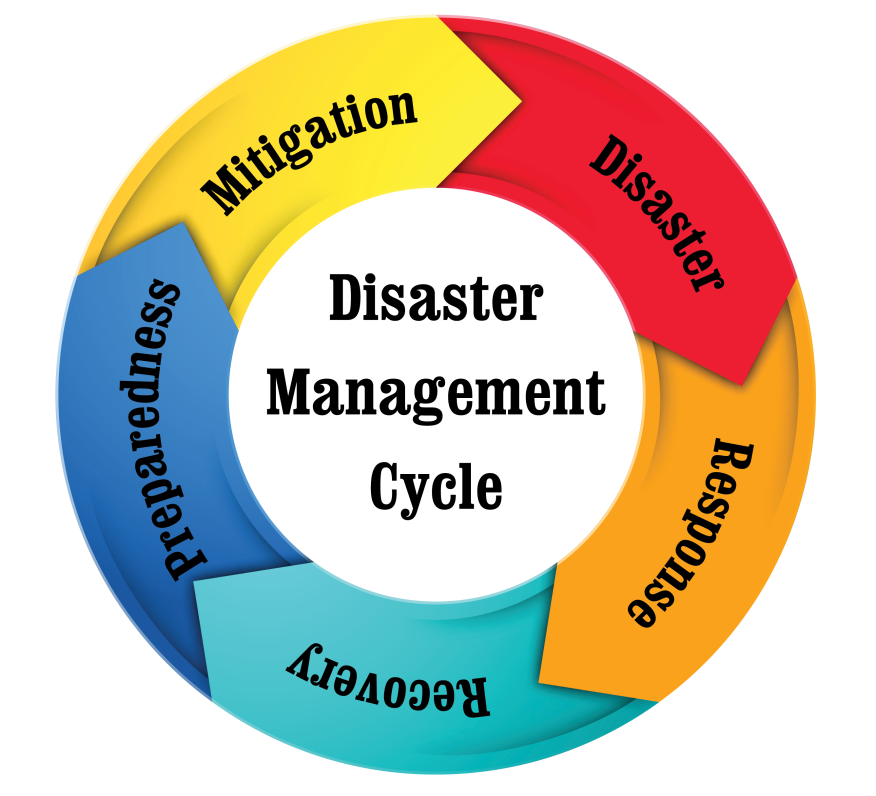

From the viewpoint of disasters and the disaster management cycle, as shown in Figure 5.2.1.3.1, we can define a situation as being well managed when the management cycle evolves smoothly.

Figure 5.2.1.3.1 – Disater management cycle

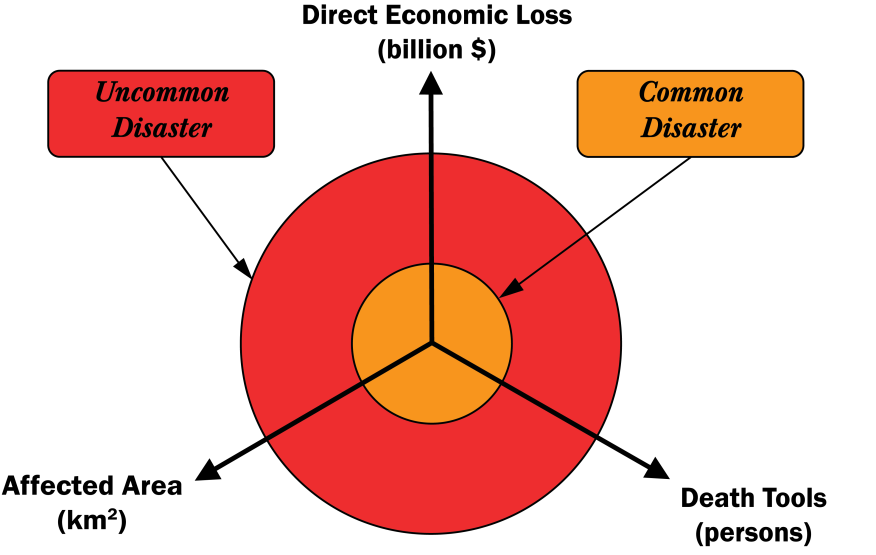

In case of combined and large-scale disasters, the management cycle does not suffice to properly characterize the situation. Combined and large-scale disasters can be recognized as the situation in which the disaster level is large and complicated, the vulnerability of the potentially affected area is high, and the capacity of the potentially affected area is not enough. Figure 5.2.1.3.2 portrays the differences between common and uncommon disasters.

Figure 5.2.1.3.2 - Difference between common and uncommon disasters

According to the definition provided by Quarentelly in 1985, “Disaster is a crisis situation that far exceeds the capabilities”.

In case of uncommon disasters, the potentially affected area has less capacity to handle it and is more vulnerable against the uncommon disaster; therefore, the potential consequences are usually great. In case of uncommon disasters, the disaster level is large and so is the disaster. In case of simultaneous occurring disasters, the capacity is not enough to resist against these. Chain-reaction disasters involve situations where the multiple disasters occur consecutively; therefore, the capacity does not suffice to resist against the disasters.

This chapter present the major experiences in the world, best practices and lesson learned from large scale and combined disasters.

In order to analyze the weaknesses in disaster management that were realized from combined and large-scale disasters, an international survey was conducted to countries that suffered from major disasters. Table 5.2.1.4.1.1 provides the details of the international survey.

| Survey items | Description |

|---|---|

| Survey date | From May 2013 to May 2014 |

| Survey countries | Member countries of PIARC TC1.5 The countries that suffered from recent well-known major hazard |

| Survey form | Character of the disaster Major difficulty in disaster management ITS application in disaster management Review and lessons in terms of the key-words below Robustness Self-sustainedness Dynamic risk management |

Thirteen case studies were collected through the survey. Table 5.2.1.4.1.2 provides a list of these.

| Disaster | Reporter |

|---|---|---|

1 | [Large scale disaster –Large-] 1994 Northridge Earthquake, USA | Herby LISSADE Chief, Office of emergency Caltrans, USA |

2 | [Large scale disaster –Large-] 1995 Kobe Earthquake, Japan | Yukio ADACHI Chief maintenance engineer, Hanshin expressway, JAPAN |

3 | [Combined disaster -Simultaneous & Chain-] 2005 Hurricane Katrina, USA | James LAMBERT Professor University of Virginia, USA |

4 | [Large scale disaster –Large-] 2007 Tabasco flood, Mexico | Gustavo MORENO President, SESPEC MEXICO |

5 | [Combined disaster - Simultaneous -] 2009 Taiwan heavy rain, Taiwan | Chin-Fa, CHEN Directorate General of Highways MOTC, Taiwan |

6 | [Large scale disaster -Uncommon-] 2010 Eruption of Volcano Merapi, Indonesia | Djoko MURJANTO Director general of highways MOI, Indonesia |

7 | [Large scale disaster -Uncommon-] 2010 Chemical Spill, Hungary | Csilla KAMARAS Engineer National Transport Authority, Hungary |

8

| [Large scale disaster -Large-] 2010 Romania flood, Romania | Constantin ZBARNEA Regional Division of Roads and Bridges Iasi ROMANIA |

9 | [Combined disaster - Simultaneous -] 2011 East Japan earthquake, Japan | Yukio ADACHI Chief maintenance engineer, Hanshin expressway, JAPAN |

10 | [Large scale disaster –Large-] 2011 Kii Peninsula Heavy Rain, Japan | Yukio ADACHI Chief maintenance engineer, Hanshin expressway, JAPAN |

11

| [Large scale disaster -Uncommon-] 2012 Cameroon flood, Cameroon | Francis NDOUMBA MOUELLE Kizito NGOA Cameroon |

12 | [Large scale disaster -Large-] 2012 Waioeka Gorge Slip, New Zealand | Brett GLIDDON State Highway Manager New Zealand Transport Agency, New Zealand |

13 | [Large scale disaster -Large-] 2013 Queensland flood, Australia | Andrew EXCELL Regional Manager MeTRO, DPTI, Australia |

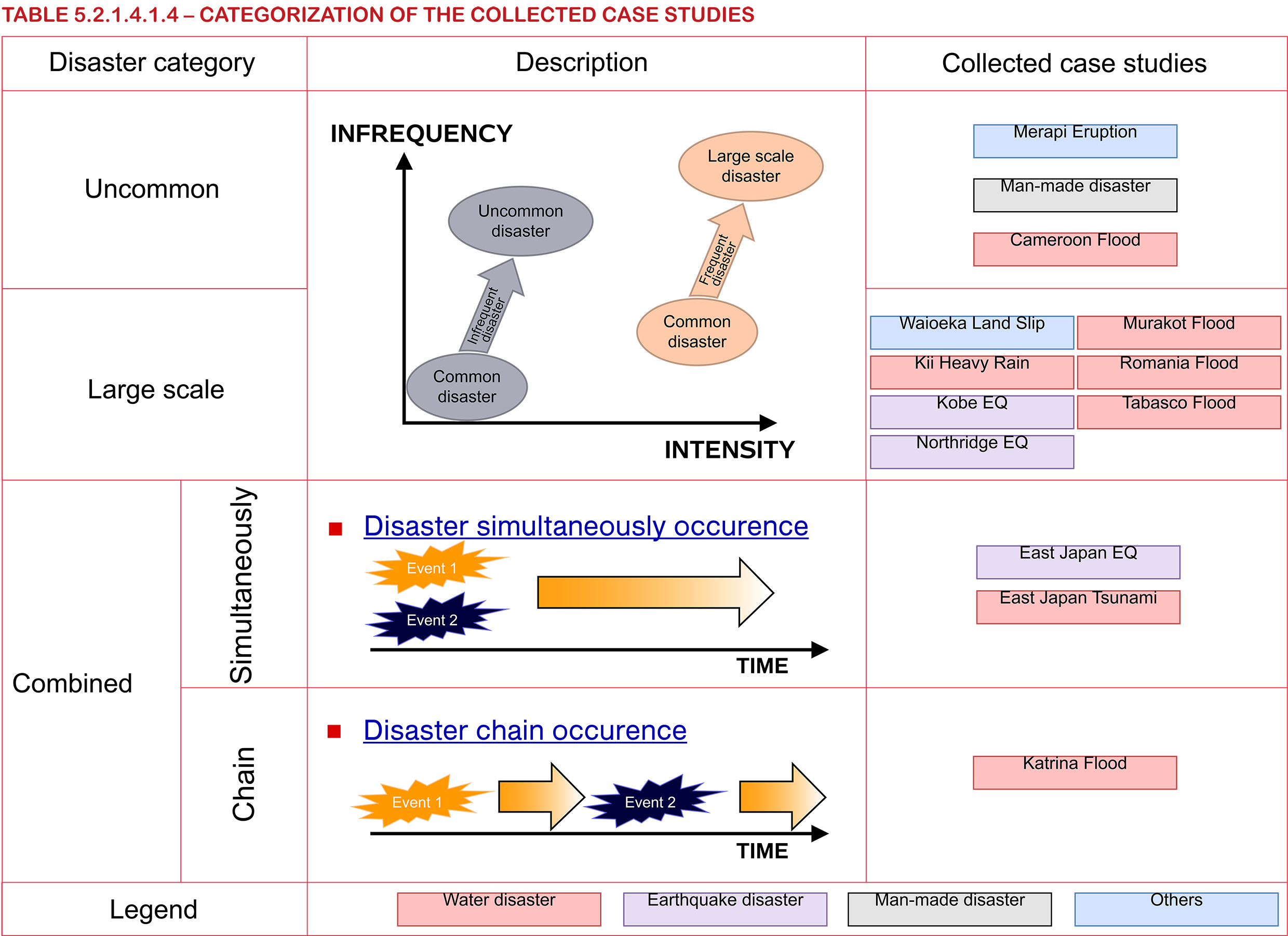

The collected experiences were categorized into uncommon disaster, large-scale disaster, simultaneously occurring disaster, and chain reaction disasters based on their mode, frequency of occurrence, scale, and status (see Table 5.2.1.4.1.3).

| Main characteristics | Disaster mode | Ocurrence | Scale of single disaster | Disaster status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Large scale disasters | Uncommon | Single | Very rare | Medium | Does not change | |

Large scale | Rare | Large | ||||

Combined disasters | Simultaneously ocurring | Multiple | Simultaneous | Simultaneous | Does not change | |

Chain-reaction | Multiple | Consecutive | Consecutive | Changes with time | ||

Table 5.2.1.4.1.4 provides a description for the aforementioned categorizations and the collected case studies for each.

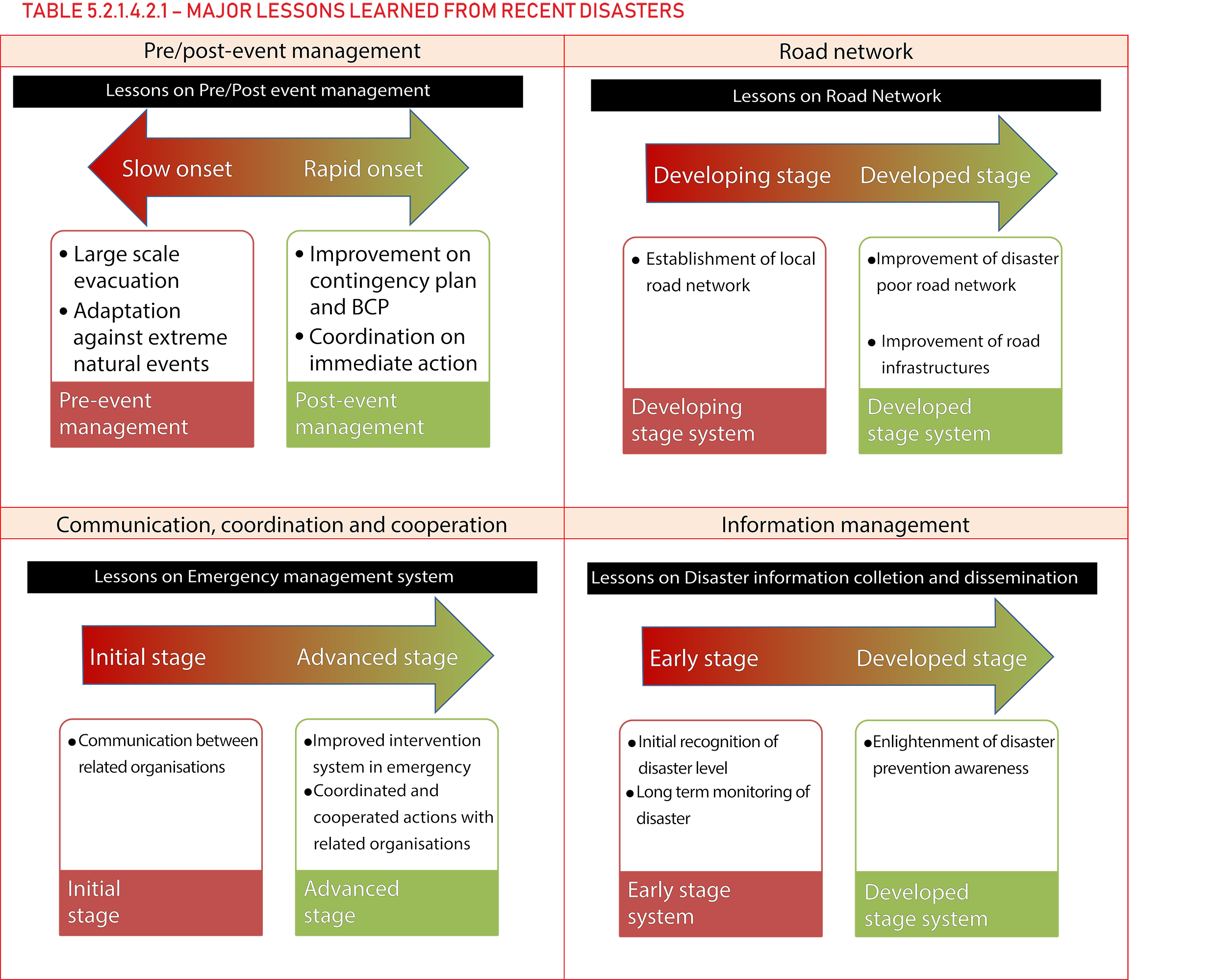

Major lessons collected from recent disaster experiences can be classified into four fields: Pre/post event management, road network, communication-coordination-cooperation, and information management, as shown in figure 5.2.1.4.2.1 – Field classification of case studies from International survey.

Figure 5.2.1.4.2.1 – Field classification of case studies from International survey

Depending on the preparedness of the affected sites, differences in disaster management are observed in each field.

There are two major hazard modes. One mode consists of slow-onset hazards such as floods, tropical storms, snow, etc., while the other mode consists of rapid-onset hazards such as earthquakes. The learned lessons are quite different between these modes. Lessons learned from slow-onset disasters are related to pre-event activities aiming to reduce or mitigate the disaster.

The most important lesson derived from the 2005 Hurricane Katrina in USA, was that there had been no preparation for mass evacuation. Mass evacuation requires coordination of several different field organizations and communication between road administrators and evacuees. Mass evacuation strategy has since been studied by FHWA and included in several references. Mass evacuation is approached from an evacuation management angle rather than traffic management.

The case of the 2007 Tabasco heavy rain event in Mexico was considered the result of the slowest onset disaster caused by climate change effects. Some engineers pointed out that this event should serve as a trigger for studies such as “Development of adaptation strategy against extreme events” and “Study on climate change effects to infrastructures”.

A redundant road network is necessary for disaster management. The derived lessons related to road network are also different between the network development levels. The major lesson is that construction of a redundant road network should be considered when designing and developing the network. For networks already under operation, major lessons derived are related to the quality of the road infrastructure (e.g. reliability and resistive infrastructure) and the standards of the road network.

In the case of the 2000 chemical spill in Hungary, the sole lifeline road was closed due to the spilled sludge for a long time. This road closure, combined with poor infrastructure of the road network, resulted in extreme difficulties in the transportation of logistics due to limited access of freight traffic to the disaster area.

In the case of the 2011 East Japan earthquake, areas hit by the tsunami were isolated due to the loss of a major road network caused by the tsunami and due to damage to local roads caused by the earthquake. High quality road network projects from now on take disaster resilience into consideration for the project cost-benefit analysis [4.2.4].

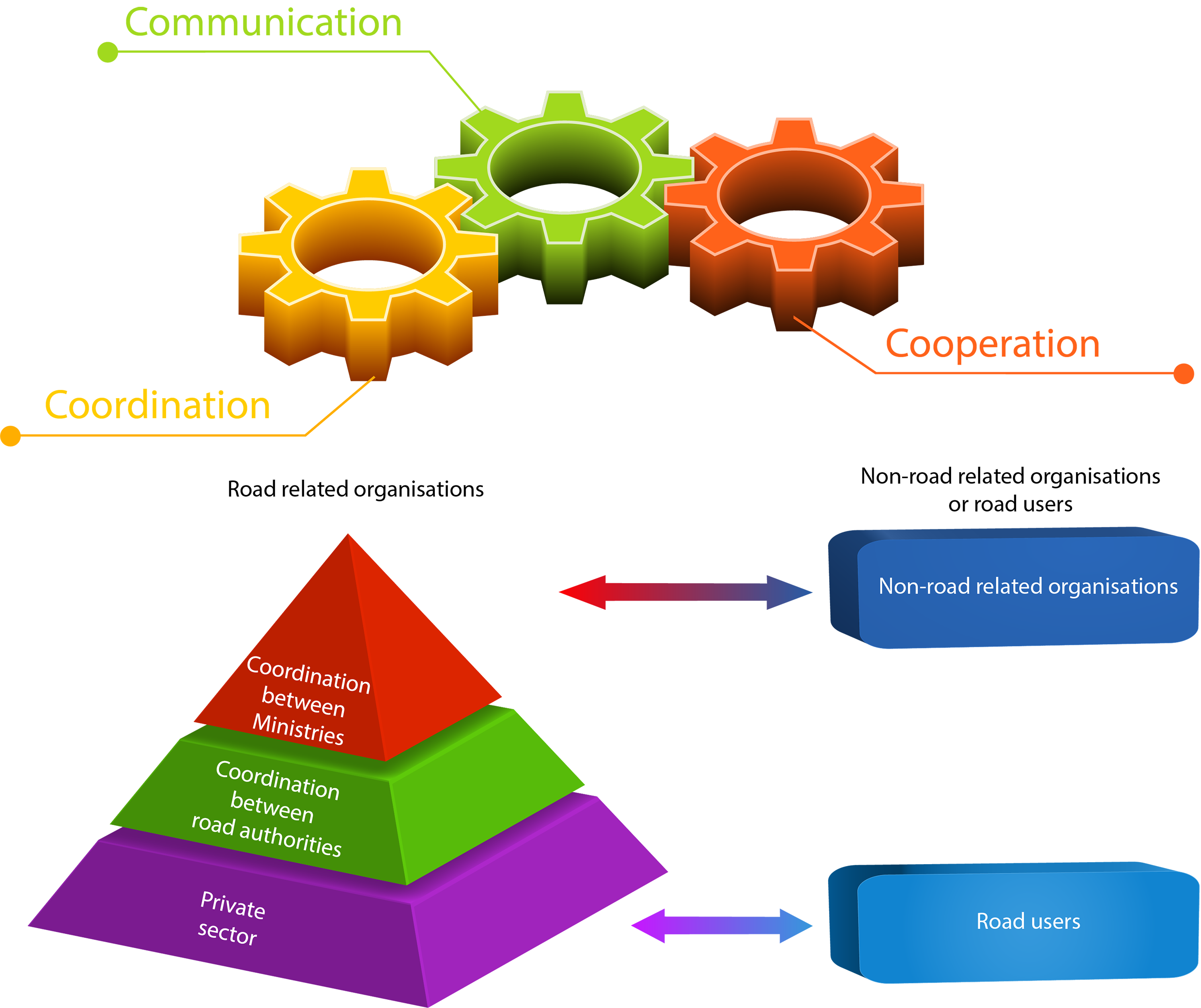

Coordination is very important in managing disasters. Coordination depends on the preparedness of the road authority, related organizations, and society. Coordination work is a process that can be enhanced by good communication among related organizations and road users, and coordination and cooperation between road and non-road related organizations, as shown in Figure 5.2.1.4.2.2.

Figure 5.2.1.4.2.2 – Communication development process and coordination pyramid

According to the experience of the 2010 Merapi volcano eruption in Indonesia, the major lesson was the limited communication and coordination between related disaster management organizations, which resulted in poor quality of the disaster work. Communication is the first step in coordination.

Advance preparedness in coordination is to make cooperative agreements with related organizations prior to the upcoming event. According to the lessons derived from disaster experiences in Japan, most road authorities prepare such cooperative agreements not only with construction contractors and consultant companies, but also with non-road related organizations [4.2.5].

Disaster information management is very important for managing disasters. Disaster information management includes:

Lessons regarding inadequate acquisition of disaster information can also be derived from the case of the 1995 Kobe earthquake in Japan, where recognition of damage level and area in the road network was very difficult; conventional communication tools were not available because of the disaster.

Similar lessons were derived from the 2011 East Japan earthquake, where electricity-based communication and information tools were inactive because of power shutdowns due to the strong earthquake and the tsunami that followed. In the case of the 2011 Kii peninsula heavy rain in Japan, long term hazard monitoring was needed to prevent secondary disasters.

An interesting and important lesson was derived from the 2009 Morakot heavy rain in Taiwan. Even though the most advanced early warning system throughout the country was in place, public awareness was limited. This resulted in improper activation of the preparedness action that was supposed to follow based on the message delivered by the warning system. As a result, the Taiwanese government acted to further promote public disaster awareness. ITS technologies are important disaster management tools for information management and for raising public awareness.

The derived lessons from each field are summarized in Table 5.2.1.4.2.1

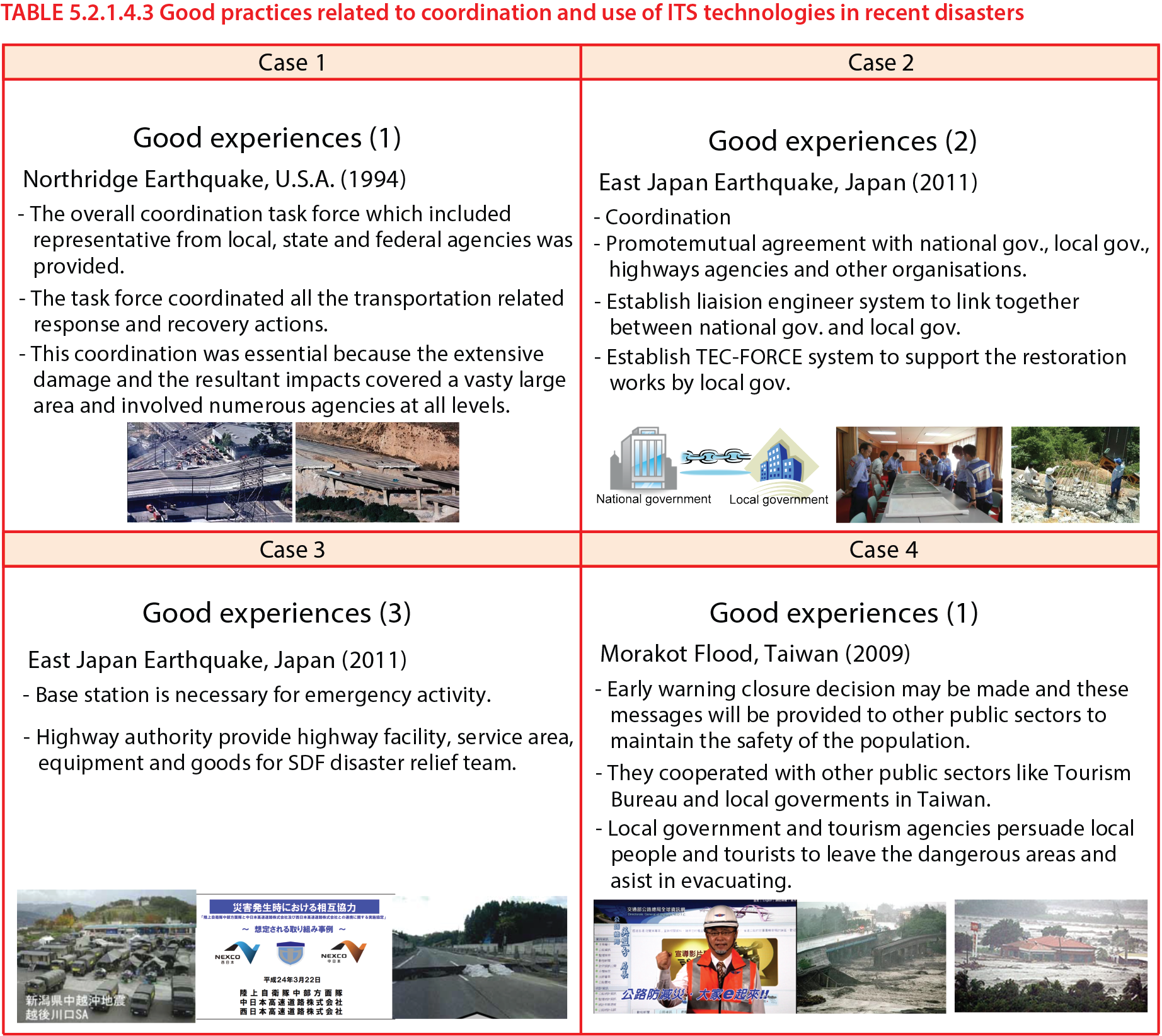

The coordination pyramid including road related organizations and non-road related organizations is shown in Figure 5.2.1.4.3. Within the road-related organizations, efforts have been made for communication and coordination. Coordination is a fundamental process in disaster management and should be enhanced within road-related organizations in order to mitigate further damages due to the disaster.

According to the report regarding the 1995 Northridge earthquake in USA, an advanced approach coordination center was established shortly after the earthquake. This center controls coordinative actions under the power of the state government.

Other advanced approaches to improve coordination have been introduced by Japan. According to these, liaison engineers and task-force engineers are sent to the disaster area in order to promote coordinated restoration actions between national and local governments. This system not only promotes coordinated action but also supports engineering issues to be solved in disasters.

The most advanced preparedness actions are being introduced in Japan. According to the lessons derived from the 2011 East Japan Earthquake, some road authorities are trying to implement mutual cooperative action not only within road related organizations but also with non-road related organizations. This involves making agreements in advance and periodical disaster exercises and drills are carried out among the agreement organizations. The agreements are usually made between national and local governments, road authorities, construction contractors, and consultant companies. The report of the 2011 East Japan earthquake outlines that quick inspection and restoration work could be initiated because of these mutual agreements. Mutual agreements with non-road related organizations such as mass media and NPOs are needed as preparedness actions for future events.

Currently, ITS technology is highly developed and it is being applied to improve traffic and safety management. Risk and disaster management are no exception.

An advanced application in the field of disaster management was reported in 2013 in Australia. The flood prediction and road closure possibility information were provided by VMS. The driver survey revealed that information dissemination using ITS technology was very effective for route selection. The continuous challenge for application of ITS technology in risk and disaster management is a continuous challenge and further research is needed in this field.

Case studies from the international survey that identify some good system developments to improve coordination and use of ITS technologies are shown in Table 5.2.1.4.3.

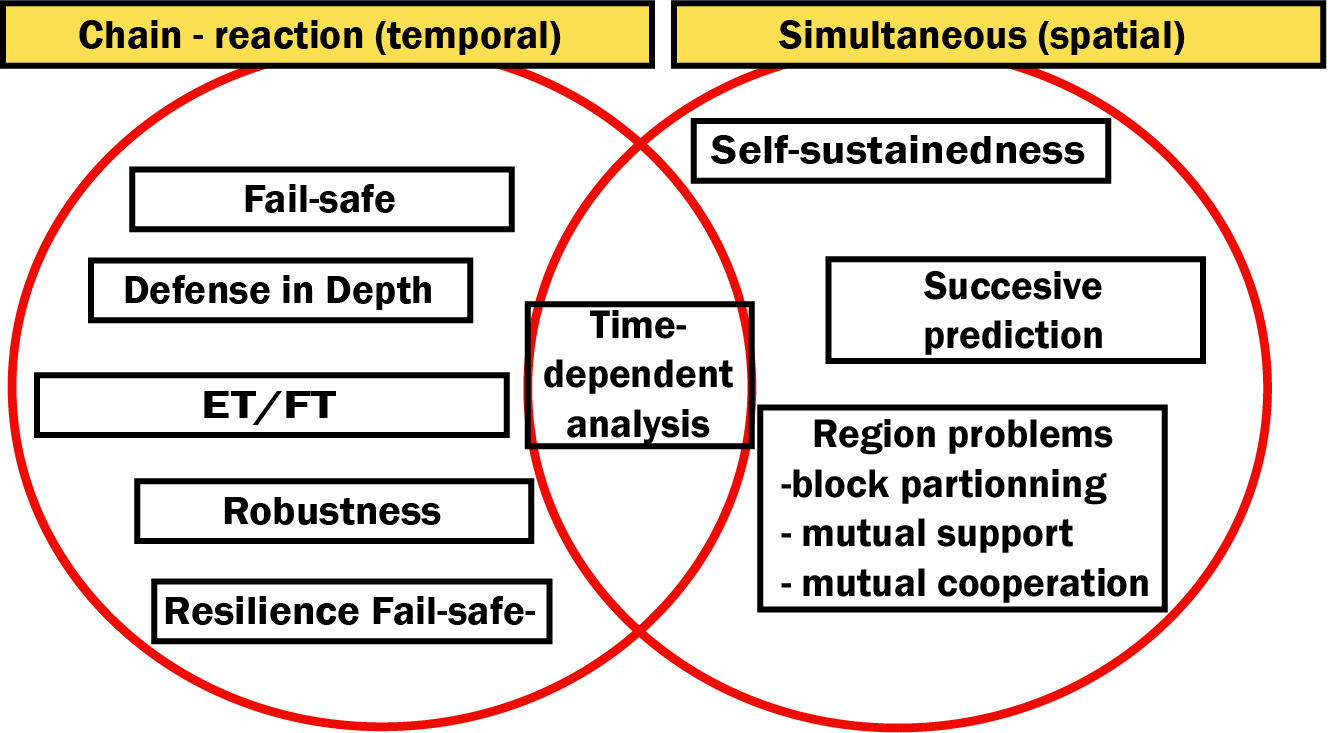

According to the lessons derived from the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident, a new concept for managing disasters in nuclear engineering was proposed.

The report indicated that the notable characteristics of the nuclear power plant event, which occurred because of the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake, were that: a) a very wide area was affected, and b) the disaster was compounded by a huge tsunami; therefore, no disaster assistance could be expected from the wider area which was also affected.

The report also indicated that the fatal event at the nuclear power plant was actually a series of separate serious events which occurred in a chain manner. This rendered the nature of the risk time-dependent. As addressing the situation involved both human actions and time-variable hazards, the most appropriate actions to be taken did not remain the same as time progressed to prevent the worst scenario for each elemental risk.

From the aforementioned features, Takada proposed the risk concept be extended so as to incorporate simultaneous failures and time-dependency in risk evolution. For this, the new concept “Safety Burst” was proposed in the report as follows:

Safety burst indicates the physical state that after either a single failure of a part or simultaneous failure of portions of a big complex engineering system with possible large failure consequence is initiated, further damage is propagating and extending and finally the expected performance of the system becomes out of control.

Many key words were introduced for improving management in two major Safety Burst situations -chain reaction-type situations and simultaneous-type failures as shown in Figure 5.2.1.4.3.

Figure 5.2.1.4.3 Key Words Introduced in Chain-Reaction and Simultaneous Type of Disasters

Among these key words, the ones indicated below and are considered very important.

From the international study, it can be inferred that the world has experienced several large and combined disasters compared to previous decades. Preparing for such disasters is one of the actual urgent needs in terms of disaster management.

Based on the study’s findings, the properties of large-scale and combined disasters can be defined using the following characteristics:

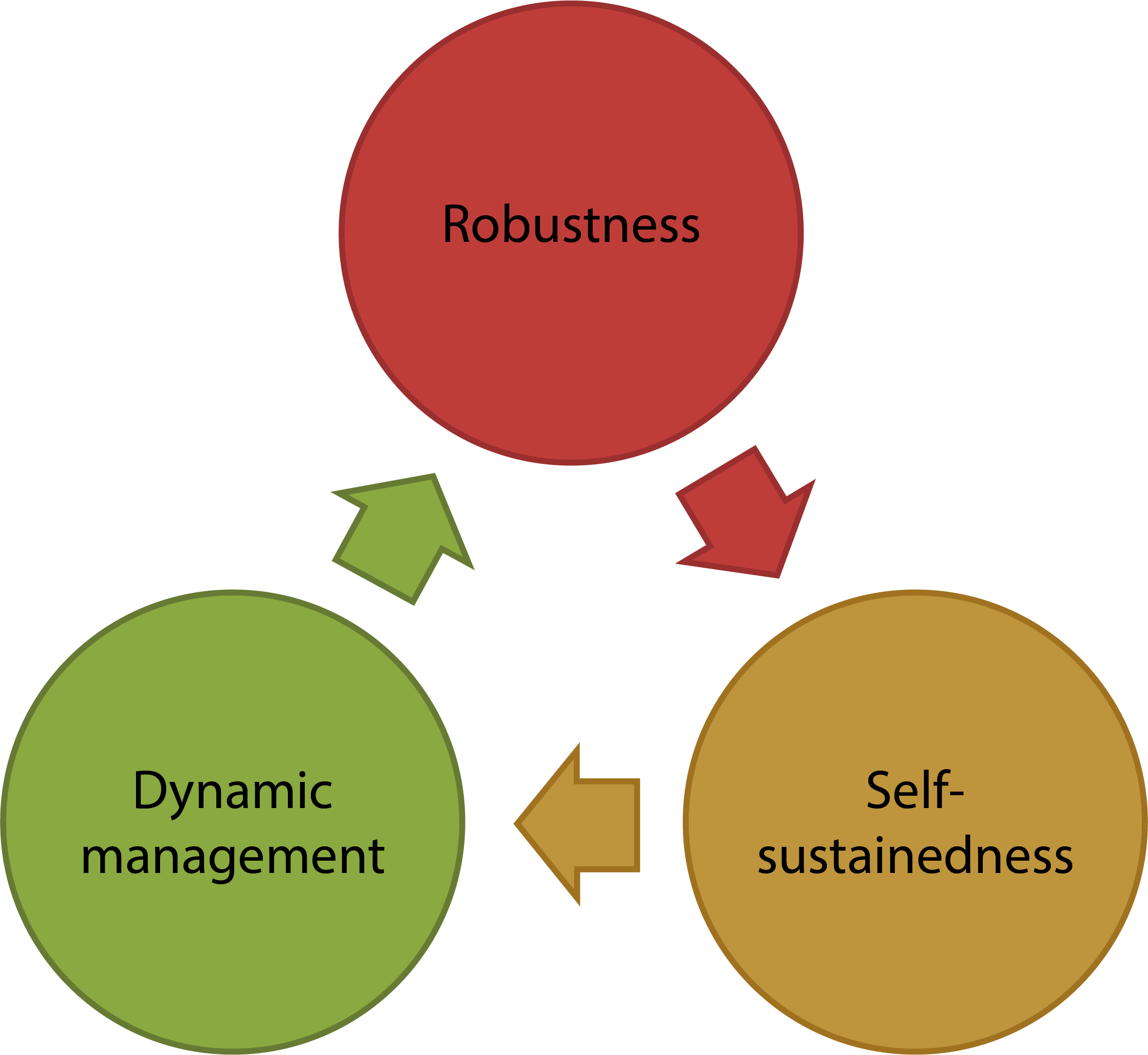

For managing those disasters in the road network, preparedness should be up to date and new concepts are needed. These concepts should take into account the important key words identified in major Safety Burst situations: robustness, self-sustainment and dynamic risk management (see Figure 5.2.2).

Figure 5.2.2 – Important key words for managing road emergency situations

Based on the findings of the international survey, no differences could be found in preparedness for large and combined hazards from that assumed for common-scale disasters. However, a new concept for disaster management considering the Safety Burst condition is emerging after the 2011 combined and serious nuclear plant disaster that occurred in Japan. The road system and network should be well prepared against safety burst situations in which damages are propagating in space and expanding in time often resulting that the expected performance of the system becomes out of control. The recommendations considering such conditions are proposed as follows:

1 Ma Zhongjin - "Recommendations on China’s regional disaster mitigation. Disaster Reduction in China" article from China National Report On International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction, 1999

2 Mohamed Gad-el-Hak - “LARGE-SCALE DISASTERS - Prediction, Control, and Mitigation”. book printed by New York, Cambridge University Press, 2008

3 Peijun Shi, Carlo Jaeger, Qian Ye - "Integrated Risk Governance. Science Plan and Case Studies of Large-scale Disasters" book printed by Beijing Normal University Press, 2012

1 MATRIX MATRIX results II and Reference Report/Deliverable D8.5- New Multi-Hazard and Multi-Risk Assessment Methods for Europe - Risk governance and the communication process from science to policy: Evaluating perceptions of stakeholders from practice in multi-hazard and multi-risk decision support models - N. Komendantova, R. Mrzyglocki, A. Mignan, B. Khazai, F. Wenzel, A. Patt, K. Fleming