Many road administrators have traditionally developed "disaster prevention plans" as an activity to enhance road disaster preparedness. The main focus of this activity is to minimize human and property damage and to maintain roads structurally. On the other hand, in recent years, there has been a growing demand to maintain roads functionally, for example, to ensure the role of emergency transportation roads and to minimize the time of disruption of supply chains. Therefore, "business continuity planning," which focuses on securing road functions, is becoming increasingly important as an activity to further enhance road function disaster preparedness.

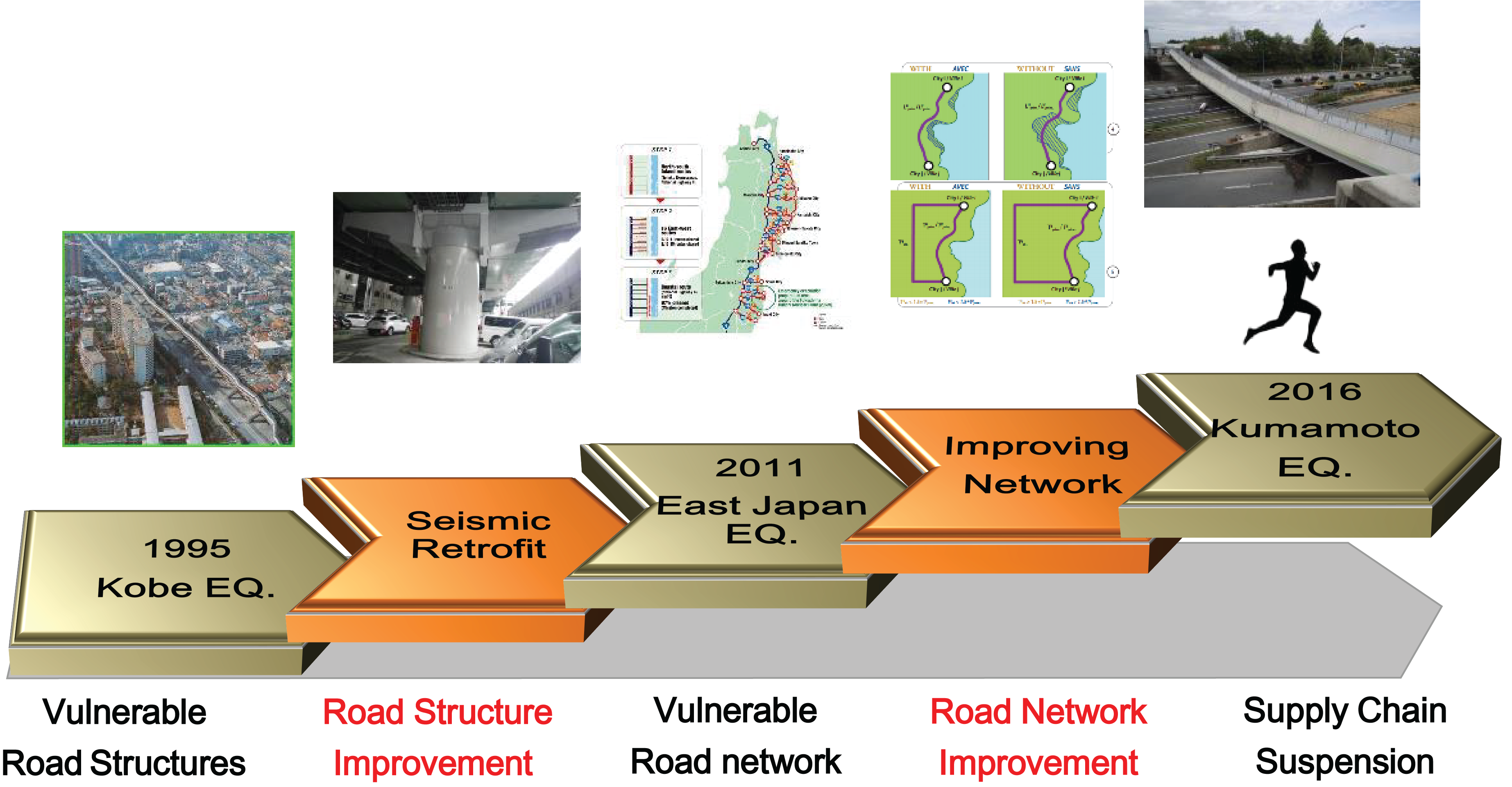

Figure 3.2-1. shows an illustration of the changes in stakeholder demands for earthquake disaster mitigation in Japan: in the 1990s, attention was focused on the seismic vulnerability of road structures, and around 2010 on the vulnerability of the road network, but in recent years, attention has shifted to the retention and continuity of road functions. In this way, it is clear that the expected role of roads in times of disaster has evolved over time.

Figure 3.2-1 Changing stakeholder demands for earthquake disaster performance in Japan

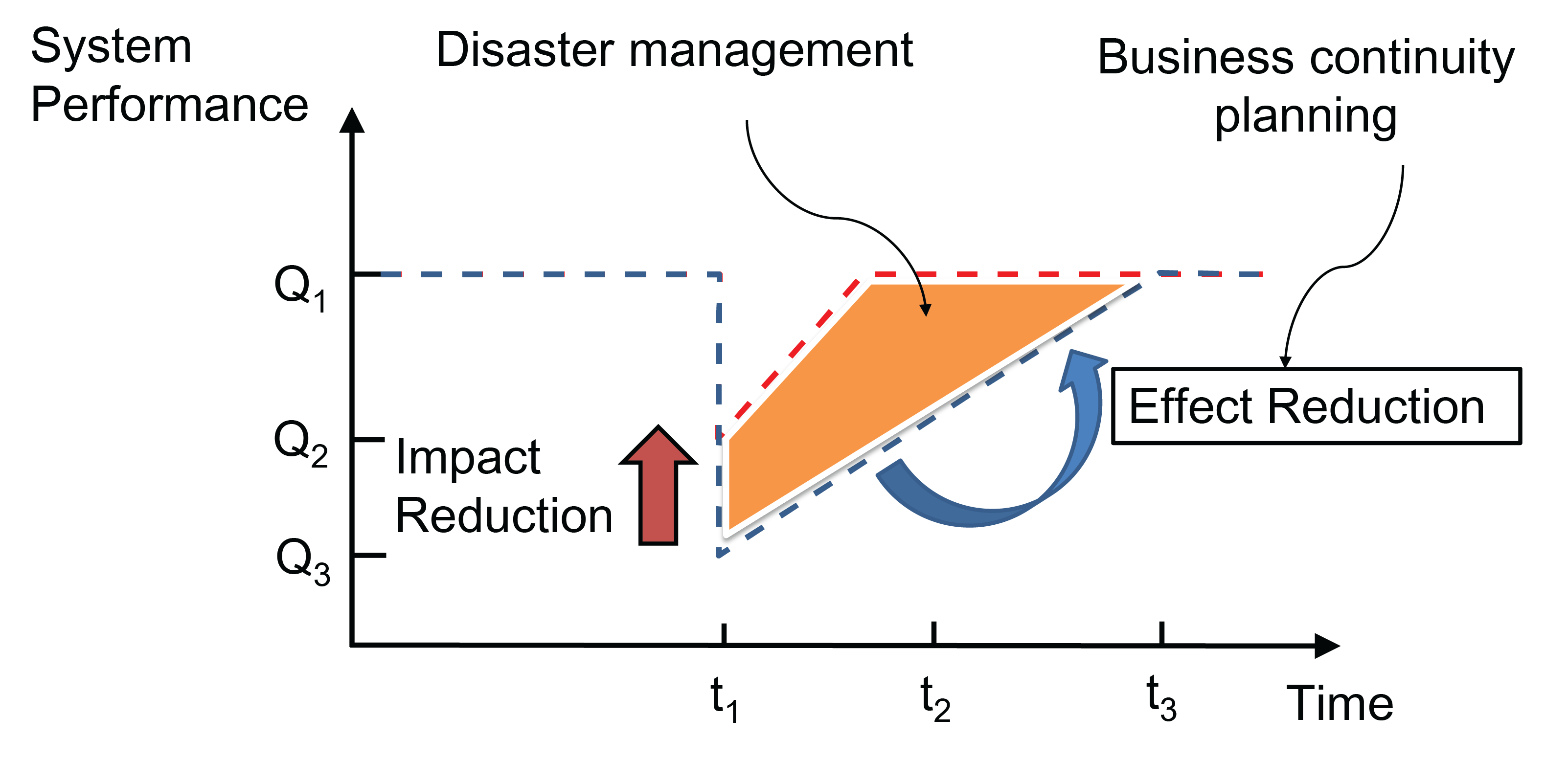

Figure 3.2-2. shows the role of disaster management in dealing with the loss of road functions due to disasters. Table 3.2-1. also compares the characteristics of conventional disaster management plans and current business continuity plans. Disaster management can be roughly divided into two categories: mitigation of the disaster itself and mitigation of the impact of the disaster. Conventional disaster management plans focus on the former, while business continuity plans include the latter.

Figure 3.2-2 The role of disaster management and its relationship to road performance

| Characteristics of conventional disaster prevention plans Minimization of human and physical damage | Characteristics of business continuity plans in recent years Further minimization of functional damage | |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Ensure safety of human life | Continuation and early recovery of critical operations |

| Indicators | Number of casualties | Recovery time and recovery level |

The following is a summary of issues that should be considered when developing a business continuity plan:

When formulating a business continuity plan, it is important to plan according to a timeline that includes cooperation with related organizations that are capable of responding to all disasters and cooperating with each other, using scenarios that assume various types of disasters.

In the event of a disaster, it is important to cooperate with related parties beyond the scope of daily operations. It is important to identify the organizations and tasks involved in disaster response, and to build cooperative and collaborative relationships based on this information in advance.

When responding to a disaster, it is necessary for everyone from the task force to the staff working on the site to have the same goal in mind. In order to maintain this consistency of action, it is important to establish a system of command and order and to develop information management tools. In addition, it is essential to coordinate with related organizations so that actions can be taken in cooperation.

It is necessary to constantly assess risks and plan pre-, during, and post-response measures according to the risks. In addition, it is necessary to prepare a variety of precautionary measures along the timeline, such as early warning information, pre-event road closure, and pre-notice road closure, depending on the risk level.

It is important to plan for the rescue and protection of road users who are stranded on the road during a disaster.

It is important to integrate elements of emergency management that are common to all hazard types and plan to fill in the gaps by complementing these common elements with unique individual elements specific to each hazard.

It is important to disseminate information on the road at all times and to build trust with road users. For this purpose, it is important to disseminate all kinds of information using all kinds of channels.

It is important to regularly review the business continuity plan using the latest risk information and to continuously improve the plan to ensure that it always addresses all risks.

In the event of a natural catastrophe or other disasters that seriously affects the functioning of roads, road managers need to ensure that the road functioning continues or is quickly restored, and that better restoration is carried out according to priority to avoid disruption of the supply chain and to support the recovery of economic activities. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to assess all possibilities of a major disaster, assume more severe situations, and consider in advance a business continuity strategy that is effective even in the case of damage caused by an unforeseen Disasters targeted by road administrators must cover events that affect all road functions, including natural disasters, pandemic disasters, and terrorism. This section outlines the business continuity plans that road administrators should prepare.

The BCP is a plan to ensure that important business operations are not interrupted in the event of unforeseen safety and security issues, such as natural disasters such as major earthquakes, the spread of pandemic diseases, terrorist incidents, major accidents, supply chain disruptions, and sudden changes in the business environment.

BCP is a plan that describes the policies, systems, and procedures to ensure that important business operations are not interrupted, or if they are interrupted, that they are restored in the shortest possible time.

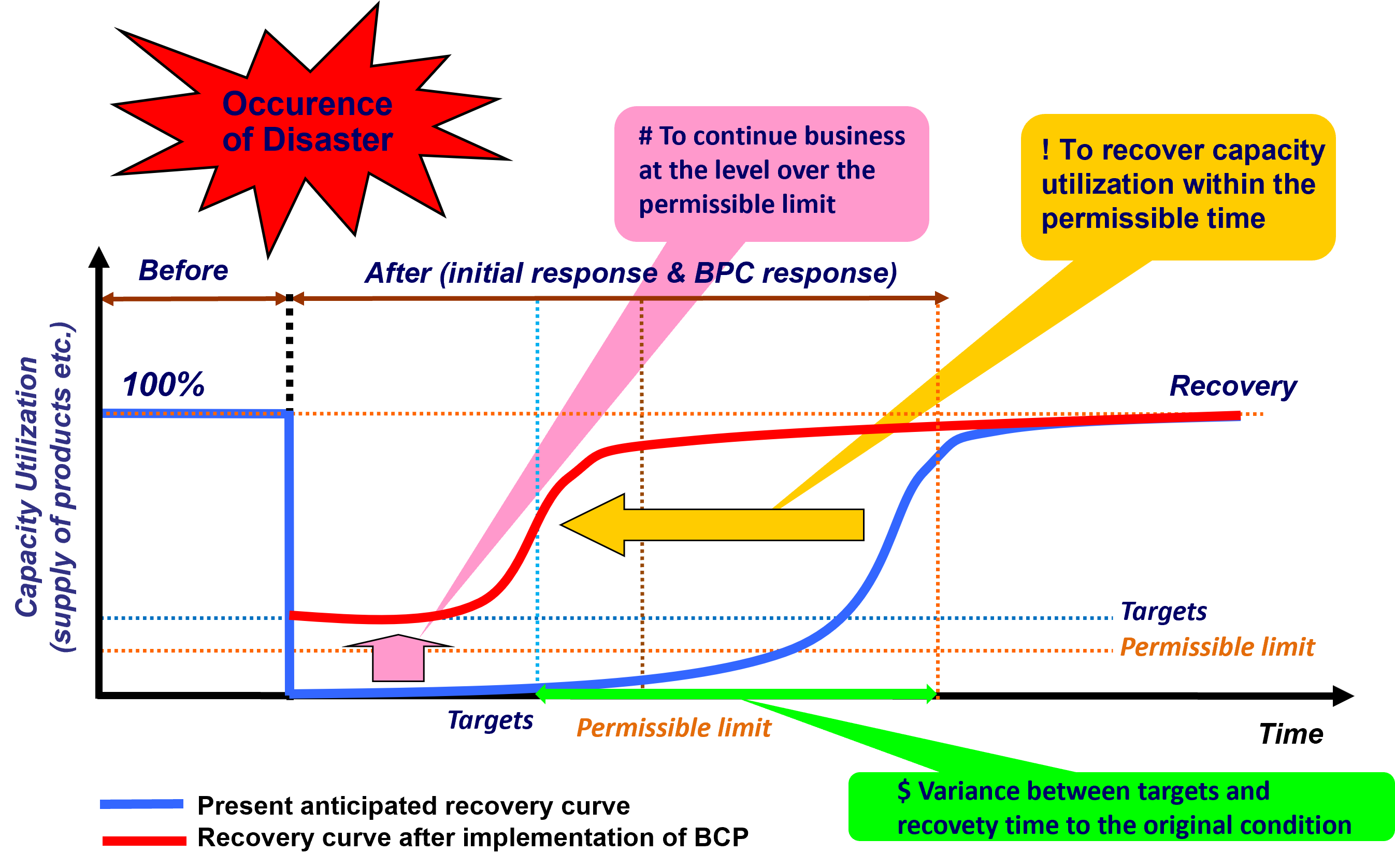

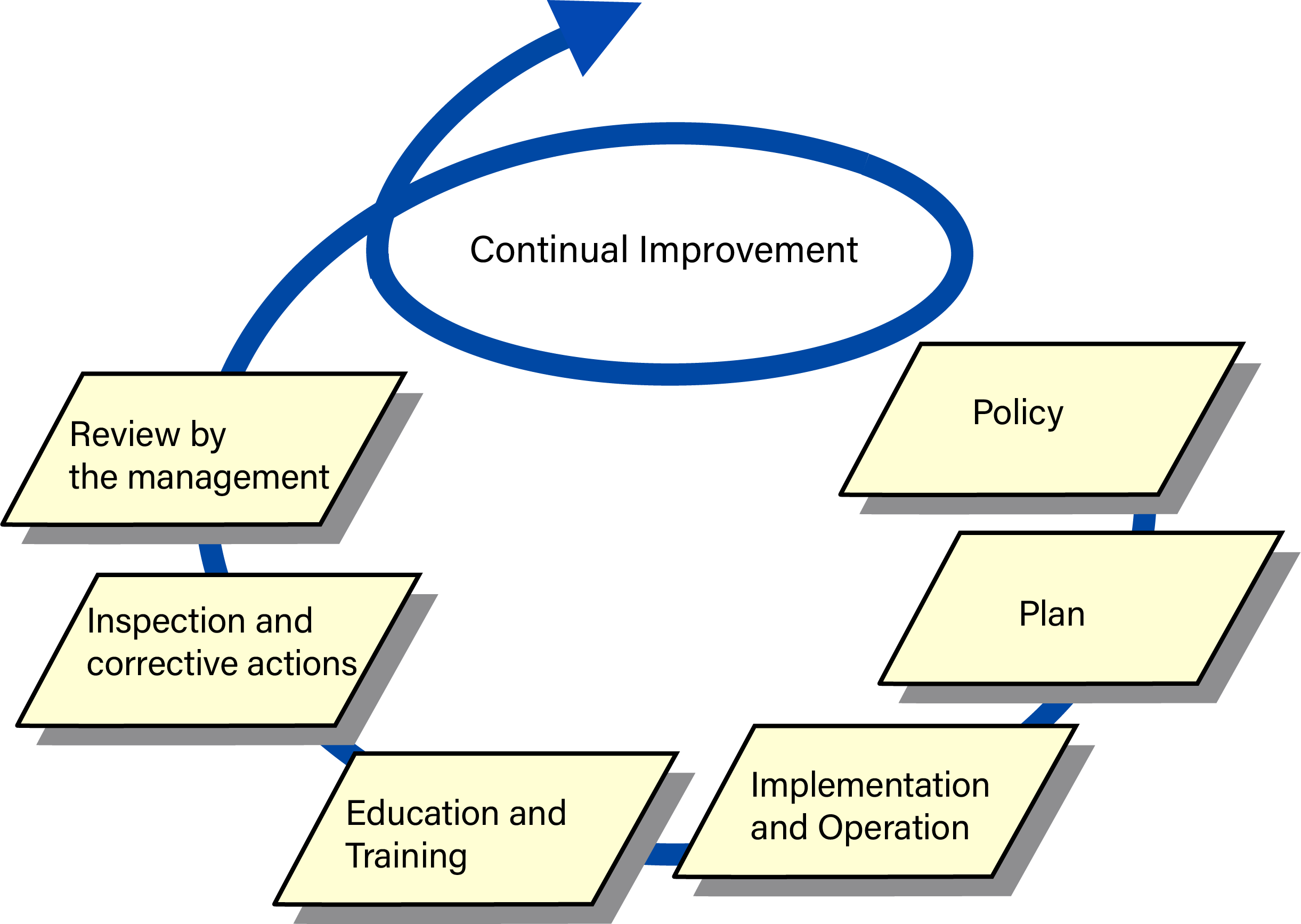

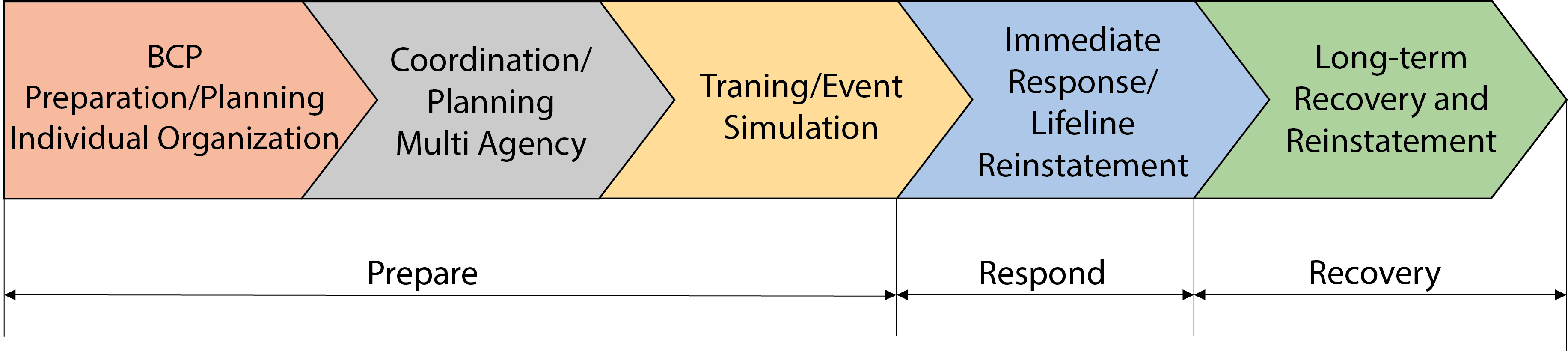

BCM refers to the management activities that are carried out during normal times, such as the formulation, maintenance, and renewal of BCPs, securing of budgets and resources to realize business continuity, implementation of preliminary measures, implementation of education and training to disseminate the initiatives, inspection, and continuous improvement. Management (BCM). Figure 3.2.1.1. shows the concept of business continuity planning 1.

Figure 3.2.1.1. Concept of business continuity planning

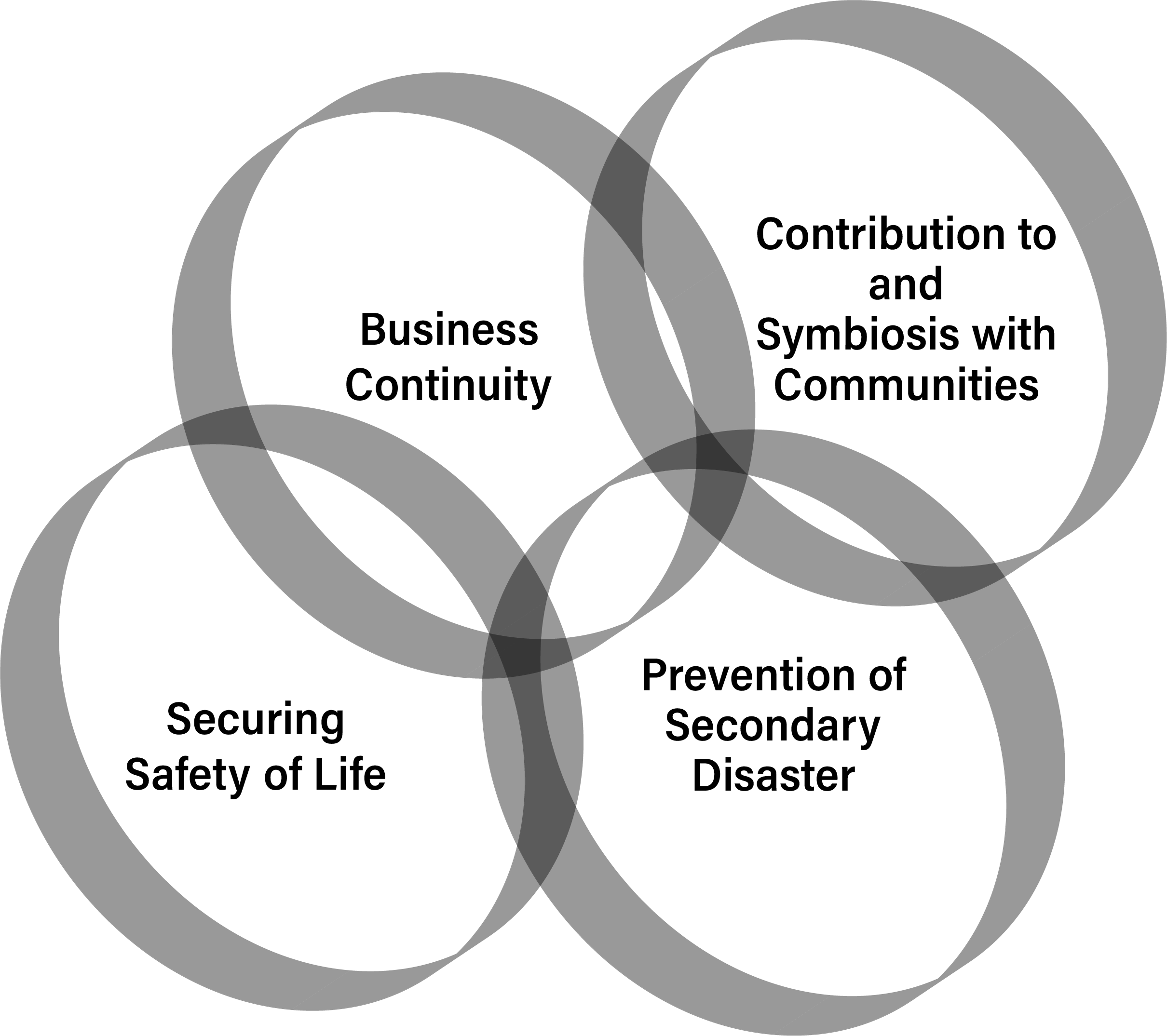

It goes without saying that the significance and importance of business continuity for road administrators lie in the rapid recovery of road functions on emergency transportation roads. In addition, it is also important to consider the following three points. Figure 3.2.1.2. shows the key points of the business continuity plan.

Figure 3.2.1.2. Key points for business continuity planning

Priority should be given to ensuring the safety of drivers on the road, customers evacuated to service areas, customers evacuated on the road, as well as employees who manage the road and their families. Confirming the safety of employees is a responsibility to ensure safety, but it is also important to understand the environment in which employees can work on recovery.

It is necessary to take all possible measures to prevent secondary disasters from the perspective of ensuring the safety of the neighborhood, such as increased damage to roads, secondary fires caused by road damage, and the collapse of nearby buildings and structures.

In the event of a disaster, it is necessary to work with citizens, government, and related organizations to restore the local environment and seek the earliest possible recovery of the local community.

It is important to periodically review and improve the formulation, maintenance, and updating of BCPs, securing of budgets and resources to achieve business continuity, implementation of proactive measures, education, and training to instill initiatives, inspections, and continuous improvement. Figure 3.2.1.3. shows the concept of the continual improvement of business continuity management.

Figure 3.2.1.3. Continuous improvement of business continuity management

Record-breaking heavy rains and windstorms, as well as associated flooding, have occurred in recent years, especially in urban areas. For such risks where the damage can be foreseen to some extent in advance, it is important to develop disaster response actions along a timeline based on the assumption that the damage will occur. In the United States, Hurricane Sandy in 2012 caused a lot of damage in many areas, but New Jersey, New York, and other states responded based on a timeline plan and succeeded in reducing the damage 1, 2.

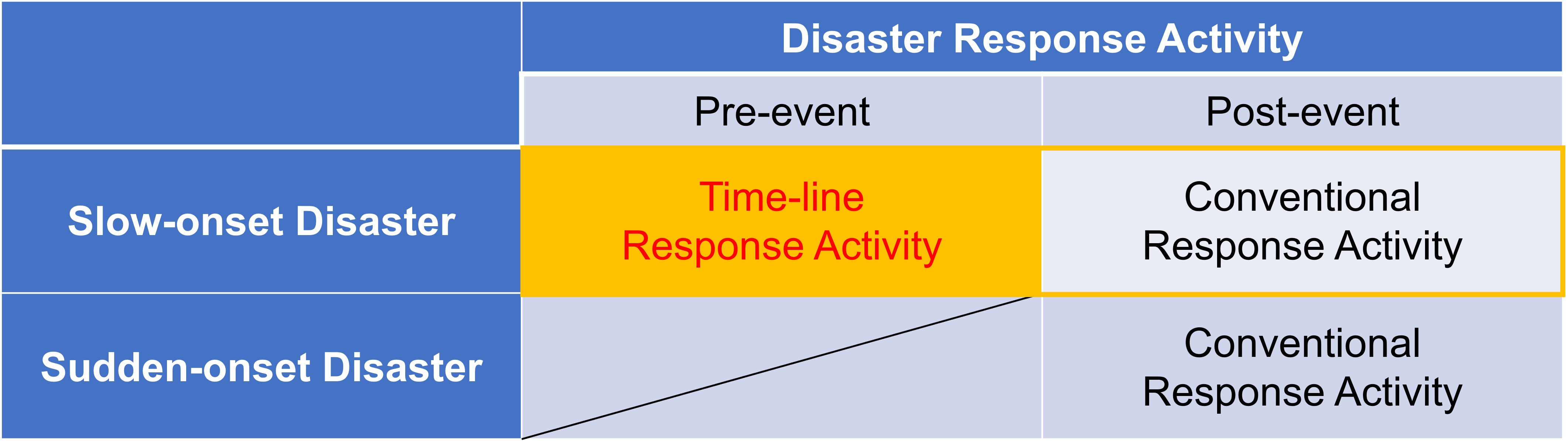

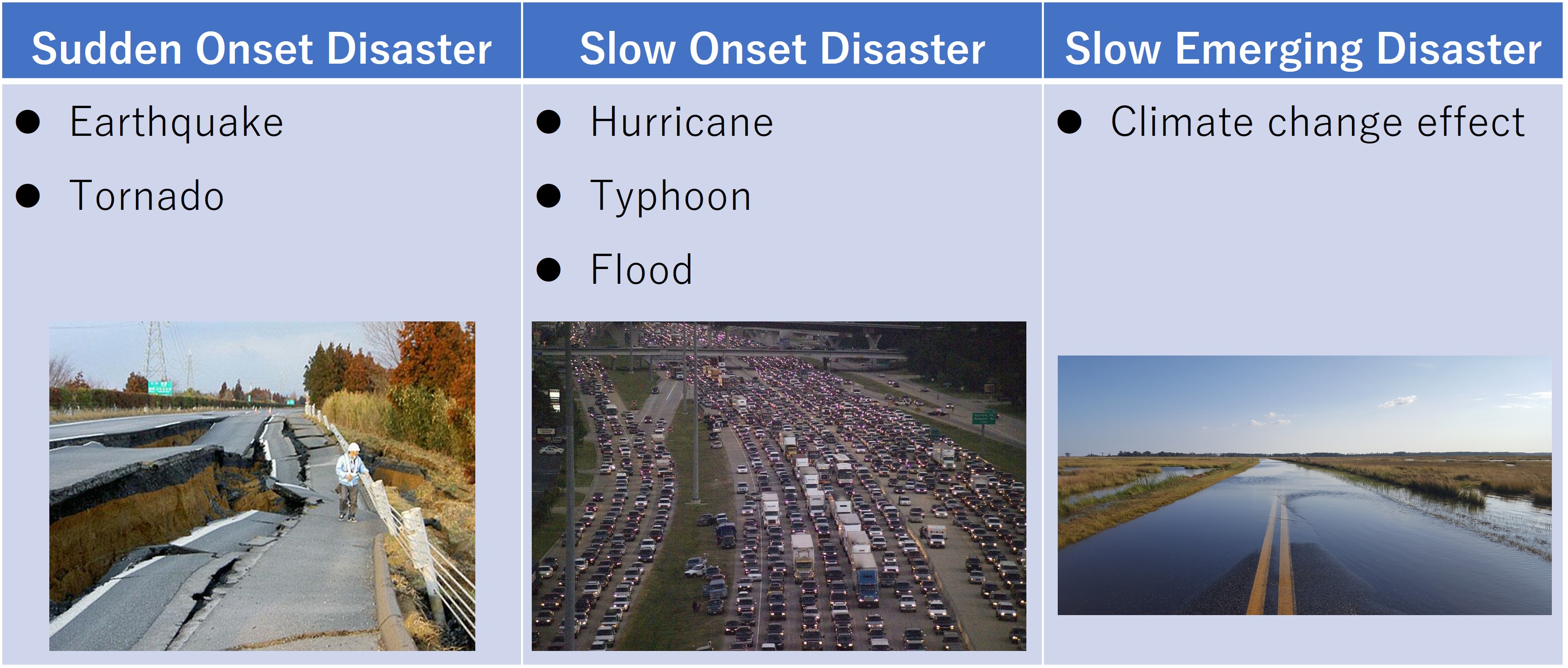

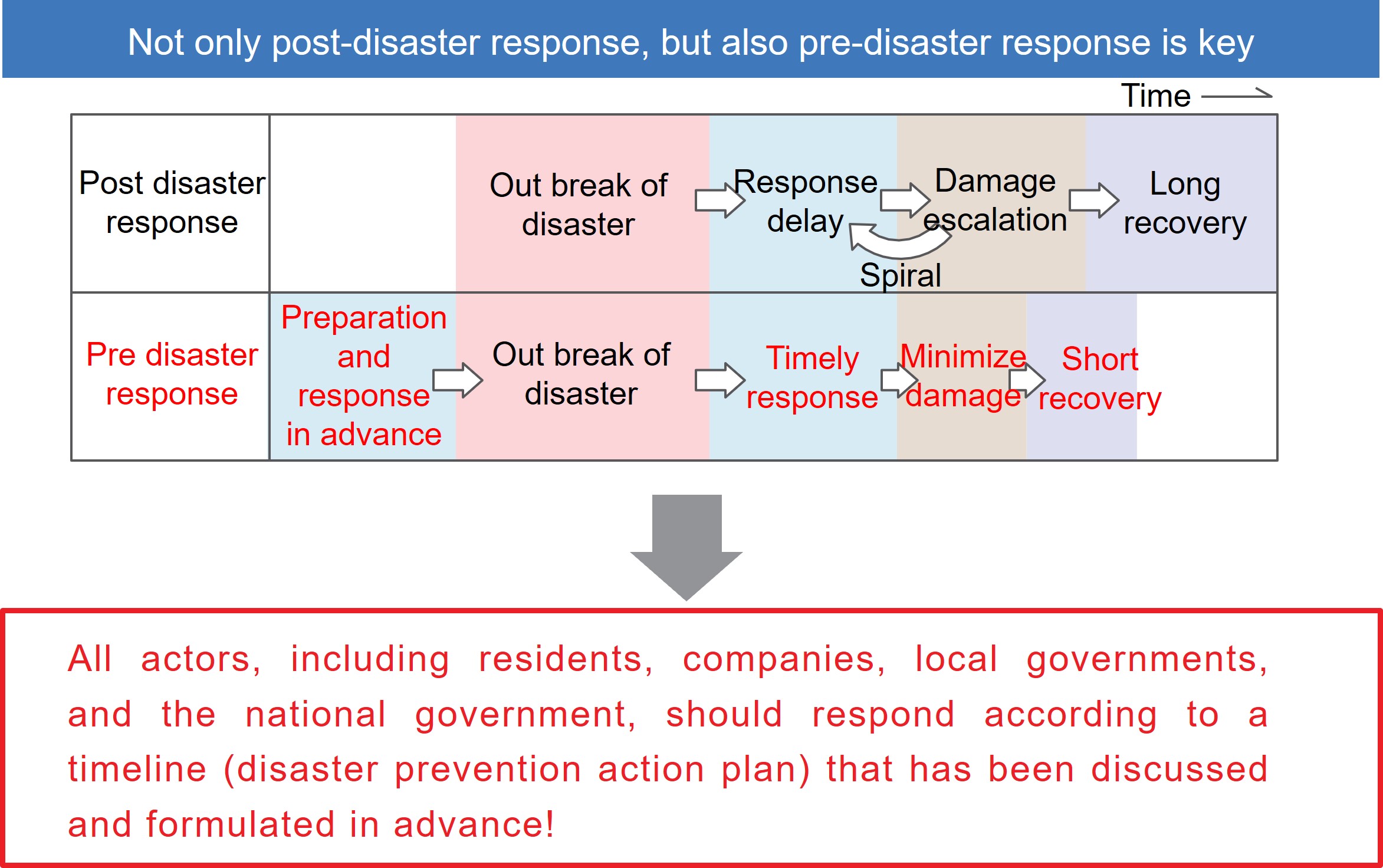

A timeline disaster response plan is a programmed plan of the countermeasures to be implemented in advance by relevant organizations in a time-line counted down from the outbreak of the disaster to deal with risks for which damage can be foreseen to some extent in advance. The purpose of this plan is to improve disaster response activities by preparing as much as possible before the outbreak of the disaster and reducing the burden of post-disaster response. The outline of the timeline plan is shown in Table 3.2.2.1, and the classification of disasters and the disasters for which the timeline plan will be effective are shown in Table 3.2.2.2. Although natural disasters are listed here, the timeline plan is also effective in dealing with pandemic cases such as influenza.

Large-scale water-related disasters such as storm surges and floods caused by large typhoons are disasters that can be predicted to some extent several days in advance. In response to such disasters, it is possible to minimize damage by the cooperation of the relevant organizations with each other, preparation of the response plans in advance based on the assumption that damage will occur, and proper implementation of those plans at the time of the disaster. The response plan should be developed based on the different scenarios: one is to prevent the damage and the other is to minimize the effect of the damage even though the damage will occur. In timeline planning, the time when a disaster outbreak is called "zero hour". The goal of the timeline plan is to complete the evacuation of not only the residents but also the administrative authorities, fire departments, and all other personnel who may be affected by the disaster by zero hour.

The timeline can be an effective method for the risks where the occurrence of damage can be foreseen to some extent in advance. On the other hand, it is difficult to use timelines for the risks such as sudden outbreak earthquakes, where the lead time between the appearance of the risk and the occurrence of damage is extremely short.

When Katrina made landfall in the southern United States in August 2005, it was a disaster of unprecedented scale, submerging most of the city of New Orleans when the levees broke. In particular, many victims were the elderly and the poor who could not evacuate by car, which pointed out the need for appropriate pre-disaster responses such as evacuation preparedness in response to an approaching hurricane. This experience has pointed out the importance of having a disaster preparedness plan in place in advance 3.

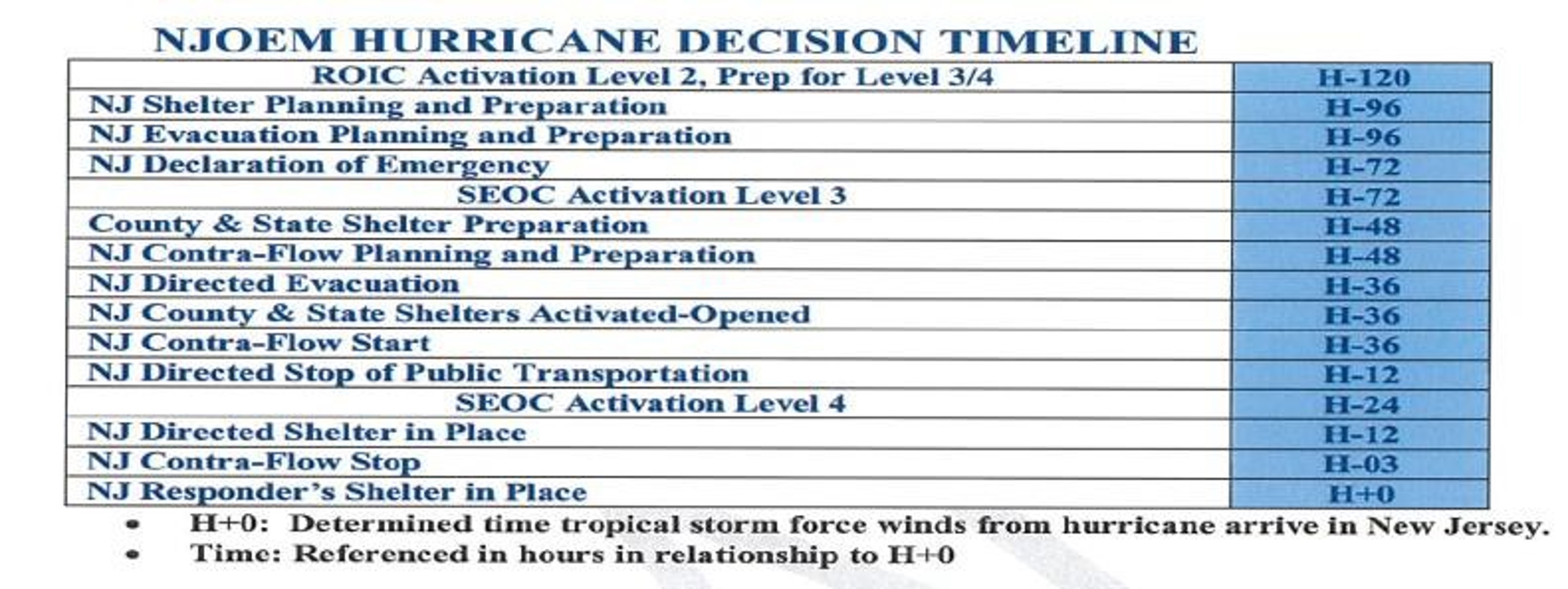

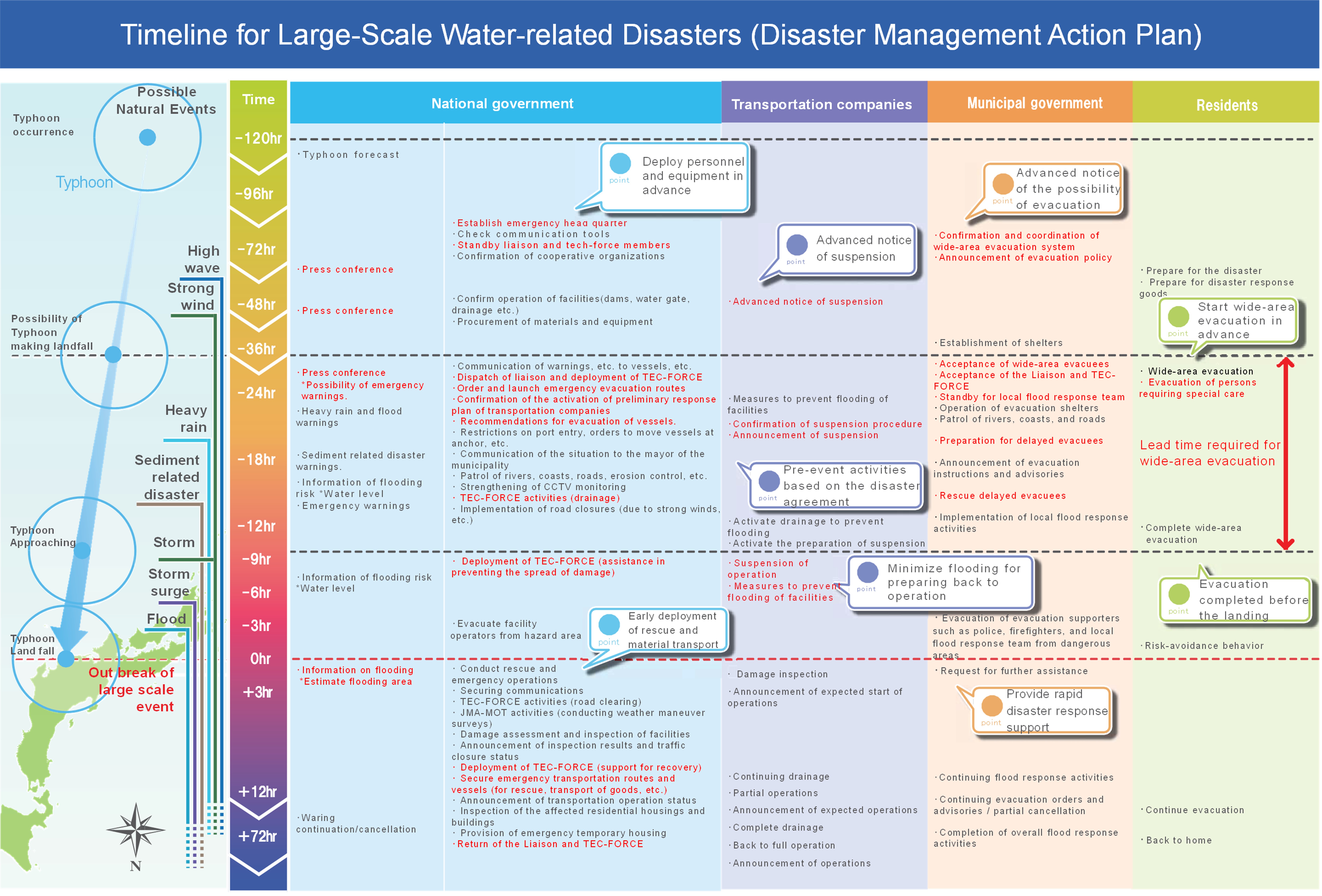

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy made landfall in North America, hitting major cities such as New York as shown in the damage photo of Figure 3.2.2.1. 4 Based on the lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina, the states of New York and New Jersey formulated disaster response programs based on scientific risk assessments in order for "pre-event response plan" and "post-event response plan," assuming that a hurricane of any scale could strike. It has been reported that the early response, including the suspension of subway and bus services and evacuation of residents according to the timeline as shown in Table 3.2.2.3 5, was successful in minimizing damage. There are also reports of active risk communication, in which top government officials call on residents and disaster management agencies to prepare for a disaster even before there is a possibility of a large-scale disaster 6.

Figure 3.2.2.1. Flooding caused by Hurricane Sandy

It is strongly recognized that there is no upper limit to disaster assumptions, and it is necessary to enhance preparedness to cope with the worst-case scenario. For this purpose, it is important to set two levels of risk and develop countermeasures as shown in Figure 3.2.2.2 7.

The first is the "prevention level”, which is the risk level at which measures are taken to prevent damage.

The second is the "response level," which is the risk level at which measures should be taken to minimize damage even if it occurs.

In response to these assumptions, the timeline disaster response plan defines the "when," "who," and "what" in strict timeline order in advance. When formulating a timeline disaster response plan, it is necessary to identify the parties involved, to divide the roles among them, and to calculate the timing of the implementation of the assigned roles, in order to plan for, for example, evacuation instructions to residents, road closures, and other disaster avoidance tasks. It is possible to mitigate damage by preparing, agreeing, sharing, and training on what should be done in the event of a disaster from the normal time among related parties. Figure 3.2.2.3 7 shows an example of the timeline for large scale water-related disasters.

In order to respond quickly and accurately, it is important not only to ensure thorough preparation in accordance with the action plan, but also to establish a basis for cooperation among the top management of related organizations, the unification of situational awareness, and problem-solving in the event of an unexpected incident.

This will have the following advantages

Figure 3.2.2.2. Importance of the pre-disaster response

Figure 3.2.2.3. Example of the timeline for large scale water-related disasters

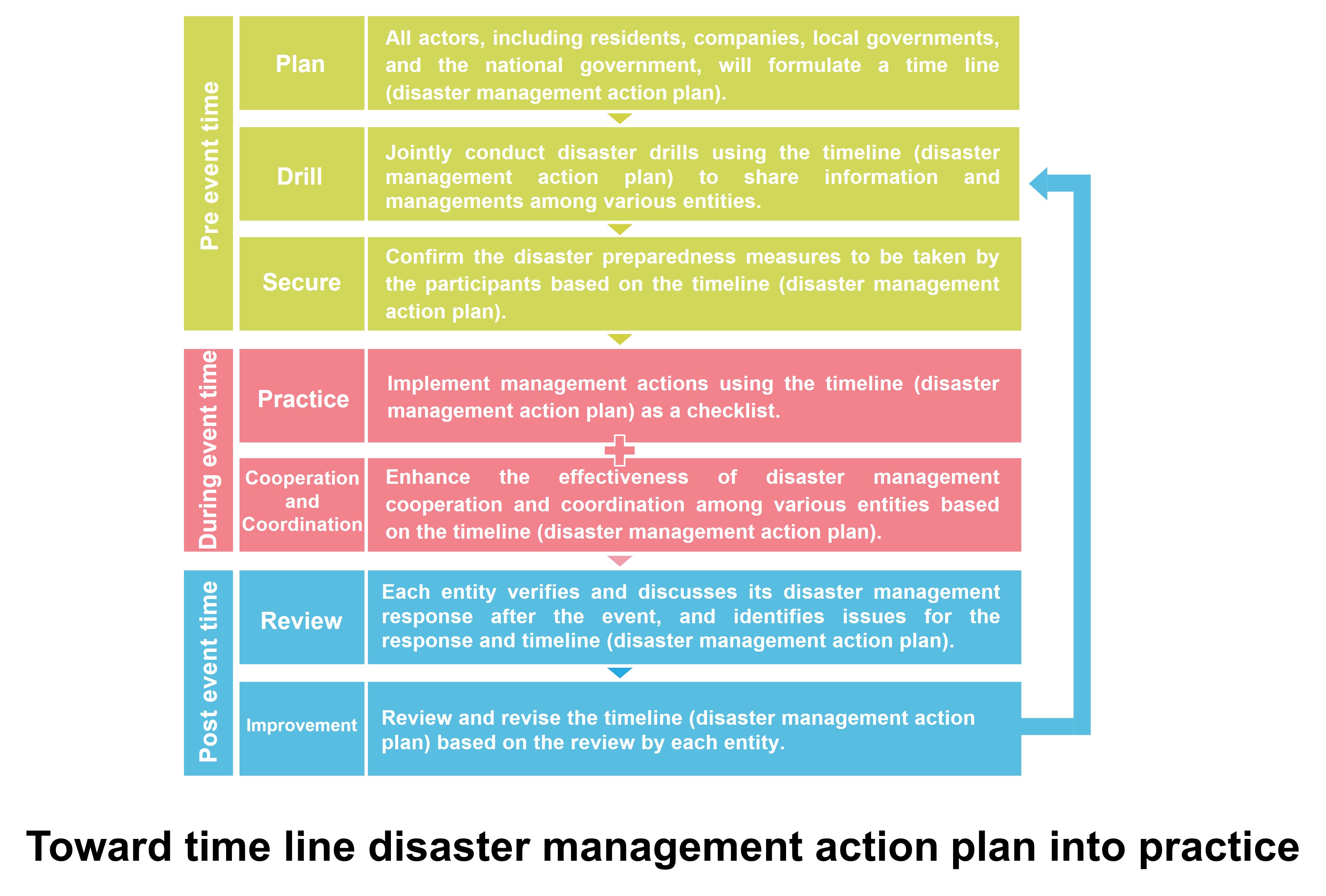

It is useful not only to have a disaster response plan in place but also to verify whether there are any problems with the plan and to constantly improve it. For this purpose, it is essential to review the plans for "when," "who," and "what" by conducting drills based on scenario events. Figure 3.2.2.4 7 shows the concept of continuous cycle for upgrading timeline disaster response plan.

Figure 3.2.2.4. Continuous cycle for upgrading timeline disaster response plan

The road network is one of the key factors in modern societies, both in economic and social terms. Road operation is primarily dependent on infrastructure. Risks to road network infrastructure and to associated control and information systems can occur in a variety of ways, either intentionally or accidentally as a result of various events. These emergency situations can be categorized into:

To optimize the preparedness, response and recovery of the road transport sector to emergency situations, cooperation with organizations at all levels (local, regional and national) and with operators of critical infrastructure is needed so as to ensure appropriate integration of these entities to emergency management.

This section includes a comparison study of Emergency Management Manuals and Business Continuity Plans for pre- and post-emergency principles, practices and actions related to road network in six countries – Australia, Canada (Québec), United States of America, Japan, Romania and New Zealand. Good practices for the different stages of the emergency management procedure are then summarized.

2. Comparison study of emergency management manuals and business continuity plans

Each country has their own detailed approach to emergency situations, however, they all follow a consistent high-level process based on three key functions.

This can be further broken down into a number of key phases as shown in Figure 3.2.3.

Figure 3.2.3. Key phases in emergency management

The following sections provide a summary of each countries emergency response processes in terms of pre- and post-emergency. This is followed by a summary of ‘best practice’ based on the existing processes and experience from the six countries reviewed as part of this report.

In New South Wales the emergency management best practice is based on the following principles:

In planning for a recovery, New South Wales continuously gather information about resources and equipment in order to establish logistics planning for the community at a local level. This means monitoring and intelligence gathering of information about supply chains, suitable locations, assets and resources. Evaluation and impact assessments carried out during and immediately after disaster event occurrence is especially valued in establishing the risk management plan for the area.

Building on this risk management plan there should also be a recovery plan identifying local recovery management structures, actions, roles and responsibilities, and be consistent with relevant State level plans. For an effective recovery these planning and managing arrangements must be accepted and understood by recovery agencies and the community. Emergency Management Committees at all levels are responsible for recovery planning.

These management arrangements call on several personnel depending on the need including:

Following a major emergency or natural disaster the best practice is for the initial impact assessment to be carried out within 24 hours. This assessment and recovery plan work together to set out the detailed action plan that will proceed.

The initial impact assessment defines the extent of damage, impact on the community and the potential need for a longer-term recovery process to take place. A delegated State Emergency Operations Controller (SEOCON) initiates this and the assessment is carried out with the assistance of combat agencies, functional areas and local government. The main duties of the combat agency will be the response operations, however New South Wales best practice emphasizes the importance of the early impact assessment info to be gathered and relayed to decide whether the damage can be managed locally in the short-term as part of the operational response, or requires more formal recovery arrangements.

Where the response operation and initial impact assessment has concluded that a more formal recovery arrangement is needed two things happen:

A State Emergency Recovery Controller (SERCON) consults with the SEOCON and a recovery Centre is established as a one-stop shop providing a single point of contact for information and assistance to disaster affected persons.

The function of the Recovery Committee is to strategically coordinate the recovery. Locally the committee is made up of Local Emergency Operations Controllers (LEOCONs) and the early meetings will be attended by the combat agency and the LEOCON to provide an overview of the situation. In the case of a regional recovery committee the effected Regional Emergency Operations Controller (REOCON) will meet to establish the composition of the Regional Committee.

The Canada Transport Agency has an Emergency Preparedness branch within their organization to:

In addition to this, in 1986 Canada and the United States re-formalized their history of emergency cooperation with the signing of The Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of the United States on Co-Operation in Comprehensive Civil Emergency Planning and Management. This agreement revolves around 10 principles of co-operation, which are to guide coordinated efforts in emergency preparedness.

The department plays a part in the following areas of emergency response: planning, exercise, training and response.

Same as with United States of America (USA), Canada deploys Transport Management Centres (TMC), which play an essential role in the response and recovery phase of an emergency. TMC participation in the National Response Framework and National Incident Management System (NRF and NIMS) frameworks are key to effective working relationships during recovery. Their roles extend to:

During an emergency or event, the TMC serves as a Transportation Department Operations Centre (TOC). It can be collocated with a state or county Emergency Operations Centre (EOC), which allows for close coordination between the Department of Transportation (DOT) and their counterparts in emergency response. It also allows the quick deployment of TMC resources for emergency response activities.

However, in an incident that spans multiple counties and even states, coordination among EOCs can become challenging. In at least one region, the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) is establishing procedures to aid communication and coordination among EOCs in an emergency.

The USA National framework for emergency response and recovery emphasizes that response to incidents should be handled at the lowest jurisdiction level capable for handling the works. The best practice model looks at all three phases of emergency response and recovery being:

The framework works to strengthen, organize and coordinate response actions across all levels based on the principle: “Mastery of these key tasks supports unity of effort, and thus improve our ability to save lives, protect property and the environment, and meet basic human needs”.

This section of the national framework is focused on capability building. In terms of the transportation sector best practice is divided into interagency communication and cooperation; emergency operations; equipment; ITS; mutual aid; threat notification, awareness, and information sharing; and policy.

In terms of coordination, the state Departments of Transportation (DOTs) and major transit agencies typically participate or take a lead role in the coordination efforts with state-level homeland security offices and state and local emergency management agencies (e.g. emergency and evacuation planning, multi-agency notification procedures, public information coordination). For regions encompassing several states Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO) take the lead role.

Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) practices differ between regions. Those identified as beneficial include:

Japan is very much exposed to natural disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis. Disaster risk reduction is covered in the budget of national and local governments. At the national level, the annual budget for disaster risk reduction is approximately $ 11 billion, which is about 1% of the total general-account budget expenditure (year 2010).

Cooperation and coordination among disaster response organizations are seen to be essential in emergency response and recovery. However, even in Japan, only highway companies or local road authorities that have suffered large-scale disaster actively worked on making such emergency agreements with other organizations. Japan has seen success on these collaboration agreements both planned and spontaneous and has based their best practice of emergency response and recovery as well as BCP on these case studies.

What stands out the most for Japan’s Best Practice for emergency response and recovery is their collaboration agreements that extend beyond emergency response type activities with frequent workshops and emergency drills. This makes implementation of the collaboration much smoother in an emergency as collaboration becomes business as usual.

Collaboration Agreement features:

Collaboration Activities:

Recovery measures are aimed at the early restoration of road services after the disaster. The best practice is to have had time-series response plans already planned out and preferably undergone drills. The targeted time of each action should be reflective of the priorities being rescue followed by provision of emergency escape routes and network restoration.

The responsibility for managing emergency situations belongs to different organizations depending on the type of road:

Permanent and Temporary Activity Operational Units are set up by the responsible organizations. These Activity Operational Units approve decisions during emergency situations relating to the road networks.

The Permanent Activity Operational Unit has specialized staff to manage risks. The size of the unit depends on the nature, frequency and severity of major risks.

Pre-emergency, the permanent activity operational unit is responsible for risk management:

It is a requirement that flood management plans are in place for those roads likely to be affected. These should cover protection, prevention and intervention. Plans for flood management must:

Intervention stocks are required close to the areas likely to be affected. These are to be maintained and remain available in case of an event.

Thresholds are to be set for intervention, and plans are followed if threshold reached:

Post-emergency, the permanent activity operational unit is responsible for:

Temporary Activity Operational Units are organized by the responsible organization and are only active during a time of emergency. This operational unit reports to the permanent operational unit.

The Temporary Activity Operational Unit is set up to provide information on:

The Civil Defense Emergency Management (CDEM) Act 2002 is intended to improve and promote the sustainable management of hazards. This relates to hazards that may impact on the social, economic, cultural, and environmental well-being and safety of the public, and property. The purpose of the act is to:

Each region is required to set up a CDEM group which brings together local authorities and emergency services in order to deliver the requirements of the CDEM.

Lifeline utilities are essential infrastructure services to the community. Identified lifeline utilities are required to have planning in place to enable the continuation of service in an emergency.

The CDEM 2002 Act defines two distinct aspects in terms of emergency readiness:

The incident response section in the specification for maintenance contracts sets out a minimal level of service for responding to incidents on the network. This ensures that maintenance contractors are prepared and ready to respond. The contractor must be prepared to:

Agencies are required to respond to emergency events by activating their own plans and coordinating their activities with other agencies:

Emergency Response Objectives include:

Transition from response to recovery:

Using the high-level approach to emergency response and recovery as established under section above (Preparedness, Response, Recovery) and the six examples of best practice emergency response and recovery of the road network in Australia, Canada (Quebec), United States of America, Romania and New Zealand, the following section provides a summary of key themes from those countries that define ‘best or practice’.

It is important that every Utility and Road Controlling Authority develops their own BCP for their organization. A key part of the process when developing a Business Continuity Plan is to undertake a risk analysis to establish what the key lifeline routes/utilities are so that an appropriate management plan can be developed for each of these and be communicated to other key organizations and the community.

It is also good practice during the planning phase to establish collaborations and supplier agreements to ensure resourcing, plant, response times, responsibilities and accountabilities and payment terms are agreed prior to any emergency event.

If an organization is both national and local/regional then development of a two part (or two separate) Business Continuity Plans is common practice. The detail provided within a local or regional plan will be different to what is required in a national plan.

Once individual Organizations have prepared their own Business Continuity Plans, it is common practice in a number of countries to establish some form of ‘Civil Defense Emergency Management Group (CDEG)’ or ‘Lifelines Group’. The purpose of these groups is to bring together Local Councils, Road Controlling Authorities and other Utility and lifeline Authorities so a coordinated national and local approach to emergency management planning is undertaken.

The CDEG groups can also form the single point of coordination and communication during an emergency, which is a critical function for the successful management and recovery following an event, although some countries establish a separate group to perform this function.

The CDEM groups focus should as a minimum cover:

A key component of being prepared for an event is ensuring regular training and emergency management simulations are undertaken with key response staff, both within individual organizations and across multiple organizations.

All countries with advanced procedures for emergency management and recovery have developed appropriate training programmes to ensure organizations are ready and well equipped to respond to an emergency.

A key aspect to all these training programmes is ensuring that an appropriate lessons-learnt process is undertaken after each training programme and implementation of business improvements is completed and audited.

Simulation drills and training should be real as possible, undertaken regularly and involve all people from workers on the road to senior management, wherever possible.

In the immediate aftermath of an emergency event there are some key processes that need to be undertaken that are consistent across all countries Business Continuity Plans. These are:

It is best practice for these plans to be “time series’ plans which change as the emergency develops. It is also common for new response plans to be developed during an event due to the developing and changing nature of an event. Ensuring appropriate resources are in place to develop and action the recovery plans is critical.

Communication with the road users advising them of road conditions is very important – Best Practice for this is discussed under section 3.2.2 above.

There were three key themes that came from the Business Continuity Plans regarding full recovery of the transport network following an emergency event. These are:

1 2003, Yoshiaki KAWATA, Crisis Management Theory: Towards a Safe and Secure Society, Disaster Prevention, Volume 4

1 2005 Cabinet office of Japan, Business Continuity Guidelines 1st ed. -Reducing the Impact of Disasters and Improving Responses to Disasters by Japanese Companies-, August

1 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/kokusai/disaster/america/

2 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/bousai/timeline/

3 2006 The White House, USA, The federal response to Hurricane Katrina: Lessons learned, February

4 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/kokusai/main/america/index.html

5 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flooding_on_FDR_Drive,_following_Hurricane_Sandy.jpg

6 http://www.nilim.go.jp/lab/beg/foreign/kokusai/hurricane-sandy-mid-gaiyou.pdf

7 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/shaseishin/kasenbunkakai/bunkakai/dai50kai/siryou12.pdf

8 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/shaseishin/kasenbunkakai/bunkakai/dai50kai/siryou12.pdf

9 https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/shaseishin/kasenbunkakai/bunkakai/dai50kai/siryou12.pdf

1 2012. Ministry for Police and Emergency Services. New South Wales State Emergency Management Plan, December.

2 2006. U.S. Department of Transportation. Best Practices in Emergency Transportation Operations Preparedness and Response Results of the FHWA Workshop Series ANNOTATED, Federal Highway Administration. December.

3 2012. U.S. Department of Transportation. Roles of Transportation Management Centres in Emergency Operations Guidebook, Federal Highway Administration. October.

4 2003. Transportation Research Board. NCHRP Synthesis 318 Safe and Quick Clearance of Traffic Incidents, Washington D.C.

5 2012. World Road Association. Managing Operational Risk in Road Operations, PIARC Technical Committee C3 Report. A-5 Example 1 BCP for Highway operation- A case study for Hanshin Expressway-Japan, Managing Operational Risk in Road Organisation.

6 2010. Romanian National Company of Motorways and National Roads NORM Regarding the National Management System for Emergency Situationson Public Roads.

7 2006. N.Z. Ministry of Civil Defense and Emergency Management. The Guide to the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act, July 1 (Revised June 2009)

8 2005. N.Z. Bay of Plenty Civil Defence Emergency Management Group Plan, Civil Defense Publication 2005/01, ISSN 1175 8902. May.

1 https://hanshin-exp.co.jp/english/businessdomain/disaster/bcp.html

2 https://hanshin-exp.co.jp/english/businessdomain/disaster/bcp.html

1 2016 Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, transport, and tourism, First full-scale installation of emergency gates connecting river embankments and highways in the Chubu regio, January

2 2018 Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, transport, and tourism, Exercise of the Self-Defense Force vehicles transporting emergency materials and equipment at the emergency gate between the Meishin Expressway and the bank of the Kiso River, May

3 2018 Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, transport, and tourism, Exercise of the Self-Defense Force vehicles transporting emergency materials and equipment at the emergency gate between the Meishin Expressway and the bank of the Kiso River, May

1 2013 Tohoku regional development bureau, Tips for Disaster Management in the Initial Response Phase, March

2 http://infra-archive311.jp/en/s-kushinoha.html

3 http://infra-archive311.jp/en/s-kushinoha.html

4 https://www.ktr.mlit.go.jp/road/bousai/road_bousai00000011.html

5 2013 National Disaster Management Council, Cabinet office of japan, Damage Assumption and Countermeasures for a near field earthquake Directly Beneath the Tokyo Metropolitan Area (Final Report), December, http://www.bousai.go.jp/jishin/syuto/taisaku_wg/pdf/syuto_wg_siryo04.pdf

6 2013 National Disaster Management Council, Cabinet office of japan, Damage Assumption and Countermeasures for a near field earthquake Directly Beneath the Tokyo Metropolitan Area (Final Report), December, http://www.bousai.go.jp/jishin/syuto/taisaku_wg/pdf/syuto_wg_siryo04.pdf

7 2016 Chubu reginal development bureau, Chubu Version of Operation Tooth Comb, March