Response activities react safely and adequately to an emergency caused by a disastrous event, and keep or quickly recover the road function necessary for emergency activities.

Response refers to the activities that take preparedness into action; to save lives in an emergency, to immediately recover road functions necessary for emergency operations, and to prevent secondary impacts on the road. Response is time sensitive. It is very important for the organizations and agencies responsible to road management, in coordination with national, regional, and local agencies, to work to restore road functions based on new and accurate information about the emergency and damage to the road. Response activities take place after an emergency occurs.

Response optimizes the execution of planned preparedness immediately after the disaster, under conditions of limited human and material resources, to secure the life of people and to recover the road function, depending on the circumstances of the emergency. In other words, in the response phase, it is important to understand the emergency and set appropriate timeline targets and implement preparedness activities. For this purpose, it is important to collect up-to-date information on disasters and their effects on roads, to restore road functions based on this information, and to provide such information to the road users. At the same time, it is important to "coordinate and work together" to secure the human and physical resources to do so. Evacuation is also an important component of the response to disasters that can be predicted (planned for) in advance, such as tsunamis and hurricanes, in order to mitigate them.

Response involves the sharing of disaster information on the road network, the connected network and other modes of transport to optimize the response. In general, "response" activities are carried out in coordination with national and local governments.

Disasters affecting roads and bridges are events or series of events that result in the disruption or interruption of function of roads and bridges caused, either by natural factors and/or non-nature, thereby causing disturbances to the movement of traffic of goods and human beings, and cause losses due to disruption of social and economic activities public. When a disaster occurs, a response measure is needed. Response measures is a series of activities carried out immediately at the time of a disaster to deal with the adverse effects caused, which include rescue and evacuation of victims, property, fulfillment of basic needs, protection, management of refugees, rescue, and restoration of infrastructure and facilities.

The level of damage to roads can be classified as follows 1:

| Typical Damage on the Road | Typical Emergency Management |

|---|---|

Buried part or all of the road due to landslide material from the cliff | 1. Cleaning road surface and drainage system |

Closure of the road due to the flow of material (lava, flood water, etc.) | 1. Clean the surface roads and drainage systems |

The erosion of the road body due to erosion or abrasion | 1. Clean the surface roads and drainage systems |

Collapse of the road due to earthquake liquefaction | 1. Clean the surface roads and drainage systems |

Collapse of the road due to earthquake liquefaction | 1. Traffic diversion and signage warning on disaster boundary (perimeter) |

The loss of road bodies due to the Tsunami | 1. Traffic diversion and signage warning on disaster boundary (perimeter) |

Cracks in the road body are divided into: | Traffic diversion and warning sign at the limits of disaster (perimeter) |

Decrease in traffic lane Settlement on the road body can caused by earthquakes, landslides or disasters other. | 1. Traffic diversion and signage warning on disaster boundary (perimeter) |

Disaster response is a series of activities carried out by government or non-government agencies immediately after the disaster occurrence. In road and bridge field, reconnecting the disconnected road and bridge infrastructures is the main disaster response purpose. In case of a disaster occurrence, government and all the related agencies inspect the road network and try to get information about damages, road and bridge network disconnections, and any aftershocks. All information must be disseminated quickly to local government institutions and communities in risked areas so that appropriate actions and measures can be taken accordingly. The next step is to assess the disaster to provide a clear and accurate picture of the post-disaster situation so that we can manage and overcome this disaster quickly and comprehensively. In this phase, assessment can be divided into two kinds, depending on what the stage is.

The first one is quick assessment, which identifies urgent needs; strategies for early recovery can be developed. Quick assessments are generally carried out using several indicators, including:

The second is rehabilitation and reconstruction assessment, which is carried out a few weeks after the disaster response takes place. In an after-disaster condition, we need to establish security as soon as possible because there is potential danger of aftershocks and the collapse of fragile buildings due to the initial quake. Security can create a more conducive and stable situation in the disaster response phase.

Disaster management in the field of public works is prioritized for immediately restoring the function of the infrastructure such as road networks, while permanent repair will be programmed immediately after the infrastructure can be re-enabled and the infrastructure budget allocated.

In dealing with every disaster, a standard procedure is needed that can be a reference in carrying out rescue and evacuation activities. The procedure starts from:

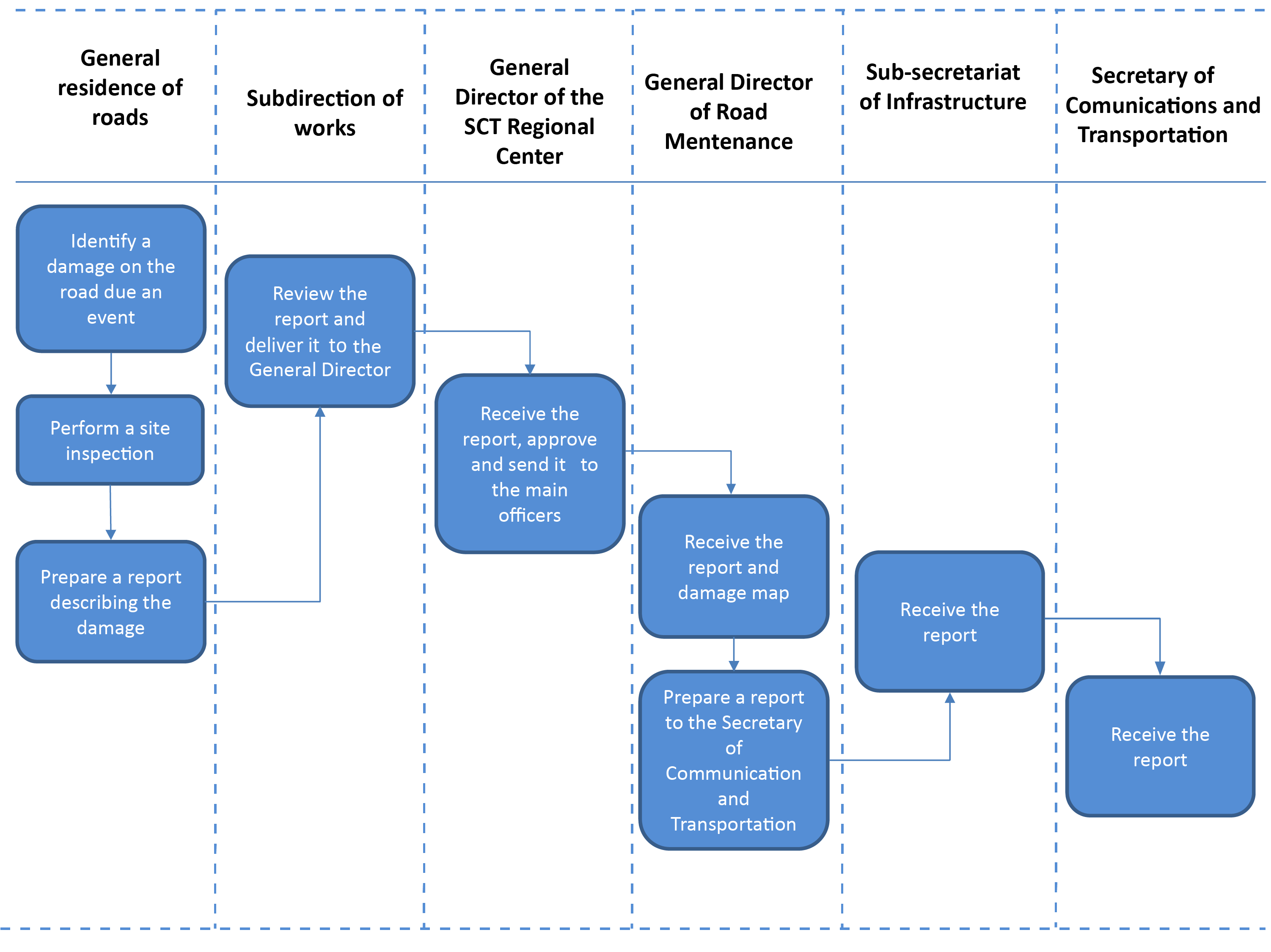

Given that road and bridge infrastructure play a vital role in post-disaster management, it is necessary to have its own handling procedures in the disaster response phase to avoid misconceptions and misinformation that can caused miscoordination. For example, the procedures for handling road infrastructure disaster response in Indonesia are as follows:

For permanent handling, local governments can submit proposals for their cost requirements, to be programmed with central government funding sources, for post-disaster management.

There are two aspects of communication when a disaster occurs. The first is communication tools for distributing information such as radio, telephone, and supporting systems such as satellite, electricity, chargers, and transmission lines. The second is information management, which is a protocol to find out who gives what information to whom, what priority is given in communication, how information is disseminated and interpreted.

Online communication can speed up the flow which is crucial due to unstable social conditions that often change overtime in the field. Therefore, it is particularly important to establish a secure and smooth communication infrastructure and facilities.

The regional and central governments send officers to damaged areas to conduct assessments related to the response plan. As an example, coordinating the mobilization of heavy vehicles that are available near the disaster area immediately. Heavy vehicles have a huge role in opening roads that might be closed due to landslide for aid distribution and officer mobilization, clearing collapsed buildings, and erecting temporary roads or bridges in case the main road is completely unusable. Cooperation between nearby contractors and local government in terms of procuring heavy vehicles and operators can make the disaster management process more effective and efficient, thus accelerating the evacuation process.

Coordination and cooperation during a pandemic are a little different because of the limitations and the need to prevent a disaster from spreading. The difficulties faced during the pandemic are in the supply chain of materials, the availability and transportation of heavy construction equipment, and the health conditions of workers. This can be anticipated by the existence of a database of material producers and a database of contractors who have construction experience to work at the disaster site. With this database, it can speed up coordination so that the response can be implemented immediately. For workers' health issues, they can do a medical test before entering the work area.

Coordination is defined as deliberate actions to align the response with the goal. Coordination can maximize the impact of a response and achieve synergy – a situation where the effects of a coordinated response are greater than the accumulation of separate responses. Whereas cooperation refers to the voluntary collective efforts of various persons working together in an enterprise to achieve common objectives. It is the result of voluntary action on the part of individuals. With coordination, assistance is delivered in a neutral and impartial manner, effectiveness of management is increased, a shared vision of the best outcomes can be developed, and an approach to service delivery can take place in a correct and integrative manner.

In the evacuation phase, government prepares various needs ranging from heavy vehicle location and readiness, human resources and operators, and evacuation plans. The main objective is to prepare an evacuation route or open up existing roads that can be used as an evacuation route and an entry point for aid and urgent logistics. It needs to be noted that the safety and health of all people involved in this evacuation process must be in the best possible condition so that it can run smoothly.

After evacuation and conducting quick assessment, emergency road and bridge infrastructure is the next priority. This step is required to identify the need for emergency road and bridge infrastructure within the disaster area to accelerate logistics delivery. Therefore, the focus of the assessment shifted to the vital things needed as follows:

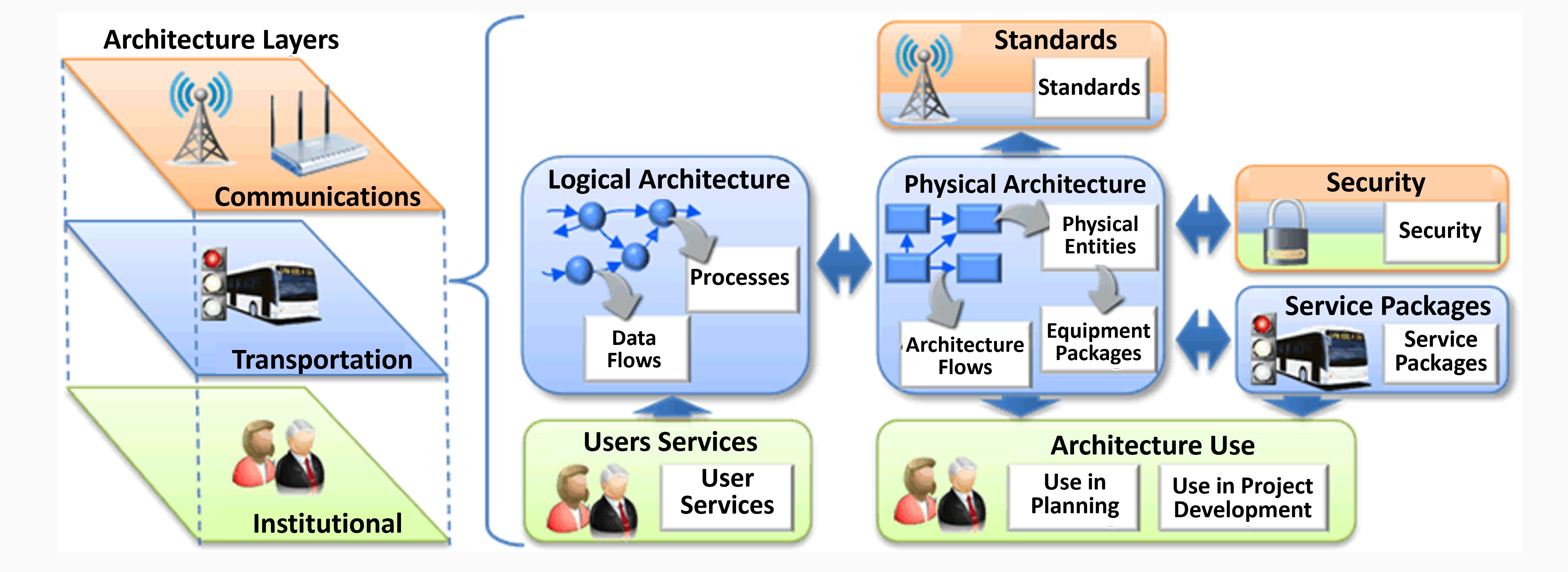

The intelligent transport system (ITS) is an advanced application which aims to provide innovative services relating to different modes of transport and traffic management. It enables users to be better informed and ensures safer, more coordinated, and smarter use of transport networks. Although ITS may refer to all modes of transport, the directive of the European Union 2010/40/EU, made on July 7, 2010, defined ITS as a system in which information and communication technologies are applied in the field of road transport, including infrastructure, vehicles, and users, and in traffic management and mobility management, as well as for interfaces with other modes of transport 1. ITS may improve the efficiency and safety of transport in a number of situations, such as road transport, traffic management, mobility, disaster management, etc.

The application of ITS is widely accepted and used in many countries today. The use is not just limited to traffic congestion control and information, but also for road safety, efficient infrastructure usage, and rapid mass evacuation after a disaster. Because of its endless possibilities, ITS has now become a multidisciplinary conjunctive field of work; many organizations around the world have developed solutions for providing ITS applications to meet the need 2.

Through ITS, government or agencies can provide solutions and methods that are faster and more coordinated because every aspect needed is already available in the application. Especially during this pandemic, while there are so many restrictions and limitations to prevent an outbreak, ITS brings many advantages to the table and government can carry out disaster management in a safer and more efficient manner.

Disasters are considered natural phenomena since it cannot be predicted precisely where and when they will take place. However, there are opportunities to reduce the disaster risk. Sufficient identification and planning support sustainable development 1. Therefore, the response shifts to a new paradigm at all stages of infrastructure development. It is necessary to distinguish records of the quality and quantity (potential) of a disasters impact to infrastructure. For example, in the areas marked as landslide-prone, the particular concrete in and specifications of roads are needed. Related to that, it is essential to implement Mainstreaming Disaster Risk, where the government immediately improves collaboration with the private sector to develop a model for development, reconstruction, and maintenance of infrastructure 2. The mapping of a disaster-prone network and construction models that are responsive to the dynamic of disasters must be implemented immediately. Moreover, the reliability of road and bridge infrastructure needs to consider disaster risk by considering the disaster-prone area in a road network system, creating a safer route during evacuation and mobilization post-disaster.

The road network needs to always be maintained in a reliable and safe condition. The following table, Table 4.1.6, shows the Disaster Relief Unit (DRU) for road construction mitigation. In addition, Figure 4.1.6 depicts a modular bridge to mitigate bridge structure for a specified span of up to 30 meters. Alternative detour routes may be used for mitigation in the event of a disaster affecting a bridge, especially on a bridge more than 30 meters long. These mitigation routes – both road class and administrator – are usually managed by the local government and must be identified for post-disaster evacuation needs. The typical DRU fleet can be seen in Table 4.1.6 3.

| Num. | Type of Unit | Capacity | Nos |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | Dump truck | 5 tons | 1 |

2 | Motor grader | 140 HP/1,3 m | 1 |

3 | Wheel loader | 1,8 m3 | 1 |

4 | Excavator track | 0,8 m3 | 1 |

5 | Backhoe loader | 0,9 m3/0,2 m3 | 1 |

6 | Vibrator roller | 4 Tons | 1 |

7 | Generator set | 20 KVA | 1 |

For bridges, one of the technologies that can be used during response is The Bailey Bridge construction which can be seen in Figure 4.1.6 below. The Bailey Bridge has an advantage in that no heavy equipment is required to assemble it. The wood and steel used in the bridge are small parts that can be transported by truck and assembled by hand without the use of pulleys.

Figure. 4.1.6 Bailey Bridge construction on Temanggung, Central Java, Indonesia (April 6th 2020)

Shifting to digital transformation by integrating several applications from different agencies or ministries is important in order to have comprehensive and accurate information on any disaster event. A risk-based digital map which overlays the infrastructure locations with seismic and geological parameters needs to be up-to-date to determine risk mitigation measures. Furthermore, digitizing the infrastructure condition database so it can be accessed remotely is important and can be a basis for formulating mitigation strategies. Some ongoing examples are prone landslide map, prone flood map, and active mountainous monitoring.

Successful integration of interagency information is key and crucial. Therefore, good coordination amongst ministries or agencies can be successfully done. When this succeeds, accurate information is available and the mitigation and strategies in handling the disaster can be achieved optimally. Interagency coordination for better disaster management includes integrating the information such as landslide, volcano, seismic data, satellite imagery data, rainfall data, road network map, road infrastructure database, and construction services database. With such optimal conditions, when a disaster occurs government and agencies can easily decide on an accurate method for handling it as quickly as possible.

In addition to integrating interagency information, the integration within the road infrastructure database is also crucial for use in disaster management to create a safe and effective evacuation road. There are several existing and new databases that need to be integrated, such as current project engagement, to identify any heavy vehicles available near disaster area, a road network map to decide the best evacuation routes, disaster prone areas, and existing road and bridge asset management. By this integration the information produced is accurate to help those in need.

In detail, developing an integrated road infrastructure database may consist of:

1 https://www.geospatialworld.net/blogs/what-is-intelligent-transport-system-and-how-it-works/

2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intelligent_transportation_system

1 United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015), UNISDR Annual Report, United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction Geneva, Switzerland

2 National Disaster Management Plan India (2016) - https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/National%20Disaster%20Management%20Plan%20May%202016.pdf

3 Road and Bridge Disaster Management (2011), Directorate General of Highway Indonesia

Disaster management activities that impact road users are triggered by the sharing of disaster information. The quality of the information provided to road users governs the quality of the subsequent disaster management. In disaster management, information management and communication should be part of planned design and execution, and be integral to an organization’s risk and disaster management plans. Improvised communication can be costly and have unsatisfactory results.

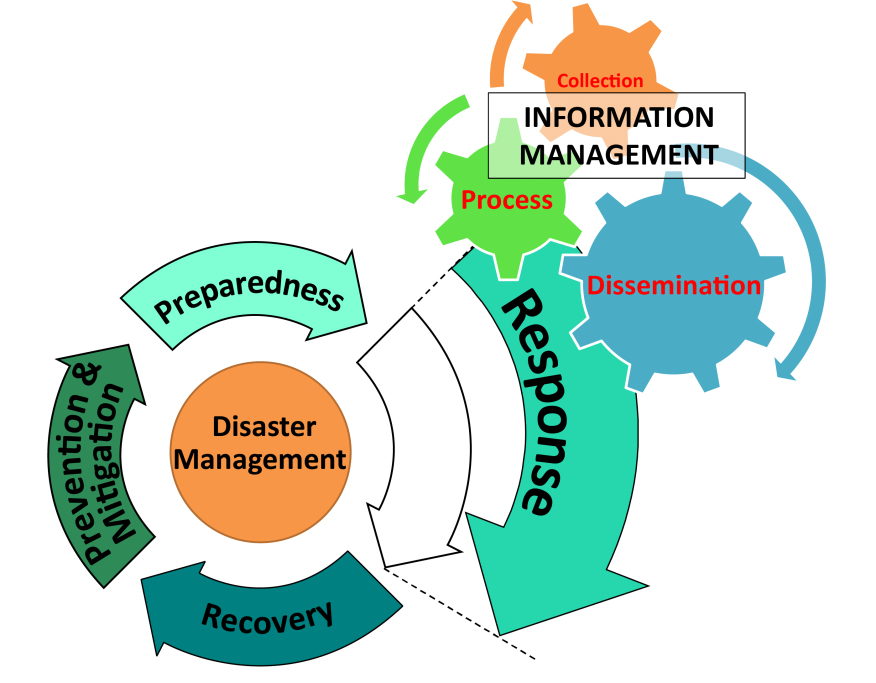

Figure 4.2-1 Role of Information Management in Disaster Management

In the 2010 Chile earthquake, a wide area of Chile’s coastal area was devastated by the giant tsunami that followed the earthquake. From the viewpoint of information management, a crucial tsunami warning system failed to alert residents to the fact that they were in the path of an incoming giant wave 1. In the 2011 East Japan Earthquake, 40% of the drivers traveling on highways at the time of the earthquake continued their driving even though they recognized the VMS signs of “STOP” or ”Earthquake Road Closure” or information about a tsunami coming from radio or other media 2. In the 2011 East Japan Earthquake, maps of passable roads delivered from car manufacturers, the web, and social media contributed to the disaster activities in the hazard region 3. As described above, information management took a main role in disaster management and current information technologies have created a new area of disaster management.

Countries that experience disasters have developed their unique management technologies based on their disaster experiences. Diverse knowledge exchange has been undertaken to share these disaster management technologies. An emerging trend is to review traditional disaster management, with its focus on making infrastructure safe, as this limits the mitigation and reduction of the impacts of disasters. According to current experiences, public engagement and public involvement activities have become an important part of infrastructure development and disaster management. Disaster management now pays more attention to disaster management activities with the public and the society 4.

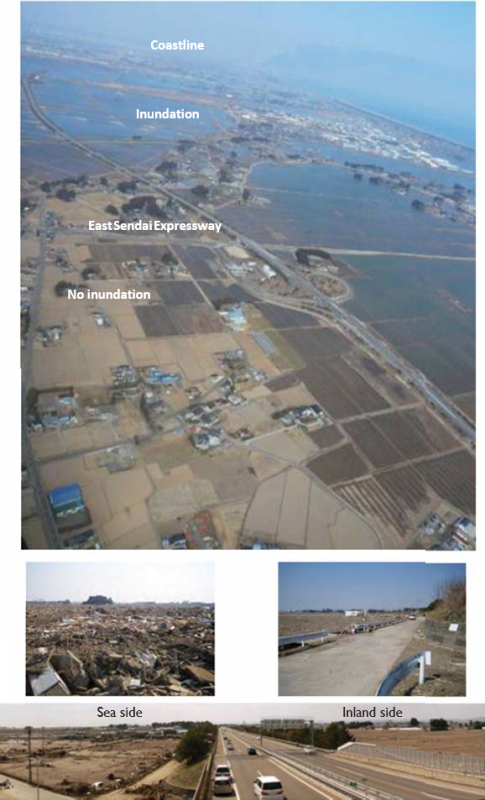

In the 2011 Queensland floods, a wide area of eastern Australia was significantly impacted by three months of consecutive flood events. According to the lessons learned from this flood, the local government leads major campaigns to engage local communities and encourage individuals to be active in preparedness for the storm season 5. As one of the lessons learned from the 2011 East Japan earthquake, a lot of the residents survived on the highway embankment in the low-lying area. Now highway companies and local residents have made an agreement to promote cooperation in daily maintenance of the highway embankment and in disaster rescue in a tsunami disaster 6.

To encourage the sharing and implementation of disaster management technologies and practices, an easily accessible, web-based risk and disaster management database has been requested. A lot of previous PIARC activities related to disaster management have been compiled. In order to promote the dissemination of this important information, PIARC developed a “risk and disaster management manual” that is available on the web. This report covers the outline of the manual.

Information is the most valuable commodity during disasters. It is what everyone needs to make decisions. Information is an essential aspect in an organization’s ability to gain (or lose) visibility and credibility. Above all, it is necessary for rapid and effective response for the areas affected by a disaster.

Public communication and media relations have become key elements in efficient disaster management. Response operations must be accompanied by good public communication and information strategies that take all stakeholders into account.

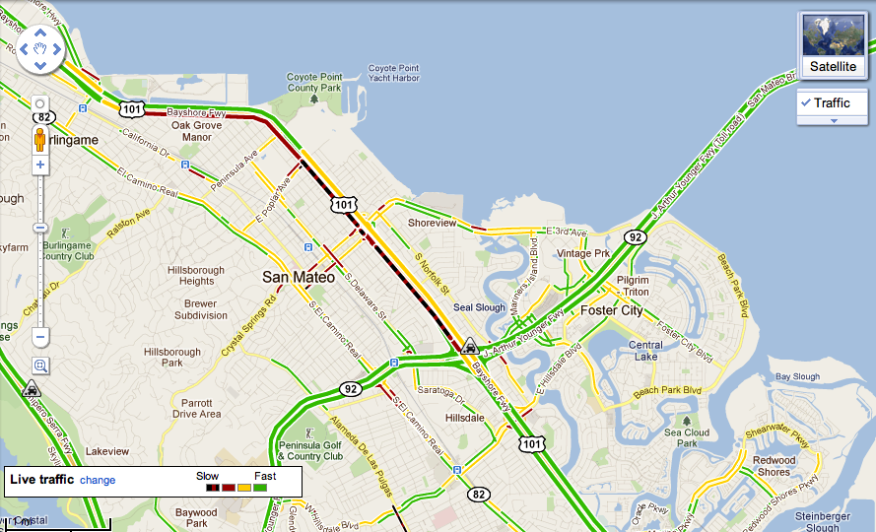

With the unprecedented increase in mobile telecommunications and social media which can instantaneously convey a huge amount of important information to road users, management of disaster information to road users plays a very important role in disaster management. Therefore, advanced technology to provide timely and accurate information management, in the pre-event and disaster phases, is critical to effective management of disasters in order to reduce or prevent primary, secondary, or subsequent disaster impacts to road users.

Disaster-prone countries have developed their unique management technologies based on their disaster experiences. In order to share these technologies, knowledge exchange forums have been developed. Current trends in disaster management include an emerging realization that paying more attention to the disaster management activities and their interaction with the public and society produces better results. This compares to the traditional disaster management approach of prioritizing making infrastructure safe. Moreover, encouraging the sharing of disaster management technologies including information management using a web-based platform provides easily accessible risk and disaster management data. This helps those countries with fewer resources to avoid the costly technology research and development phase and go straight to implementing proven technologies where they will have the greatest impact.

In the development of this topic, a large number of disaster specialists from the PIARC member countries have participated in analyzing important needs in information and communication in disasters.

The management of information and communication should be part of a planned process that road organizations use to manage risk and disaster. Information and communication management are currently considered an indispensable part of disaster management. Both the protocol development and tool investment in information and communication management are becoming very important tasks that should be developed by road organizations. Information is the most valuable asset not only during a disaster but also in the pre-event and post-event situation, so it is very important to study the ways of managing disaster and disaster related information and data.

Disaster management activities rely on information, which enable better coordination among all agencies who deal with emergencies. This task will be more effective where the information management issues are well understood and there is an exchange of information between agencies and the public through appropriate communication techniques and processes. It should be noted that the tasks of collecting, communicating and disseminating information in emergencies is always dealt with in complex and stressful situations, where the public require only the most immediate and urgent information.

Such information should be collected, analyzed, and provided to public and technical agencies. It is also important to understand that information for the public and technical agencies should be consistent for better understanding of disaster situations and to assist individuals in preparing against subsequent and anticipated events. However, public information and technical information are required to be presented differently to communicate effectively to different audiences. Effective and efficient procedures for communication and administrative structures for sharing this information are required and should be implemented early.

New computer software and other tools based on new technologies greatly assist in information processing and collection. Social media, web media, and social media services are very powerful tools to almost instantly disseminate any kind of data to many people worldwide. Current technology creates a real advantage; when combined with databases, it improves information analysis and sharing. However, excessive reliance on new technology can be inappropriate. Road administrators should be prepared for electricity outages and damage to communications facilities – such as phone towers – to disrupt communications. It should also be pointed out that road administrators should consider sharing information with other countries in order to get a good comparison of results.

In this report, current practices regarding disaster information management of different countries – through an international survey and collection of case studies – were reviewed to identify the best practices for dealing with an emergency or disaster situation. Recommendations have been made to help road organizations understand and manage the context of the disaster and facilitate information management and public communication tasks.

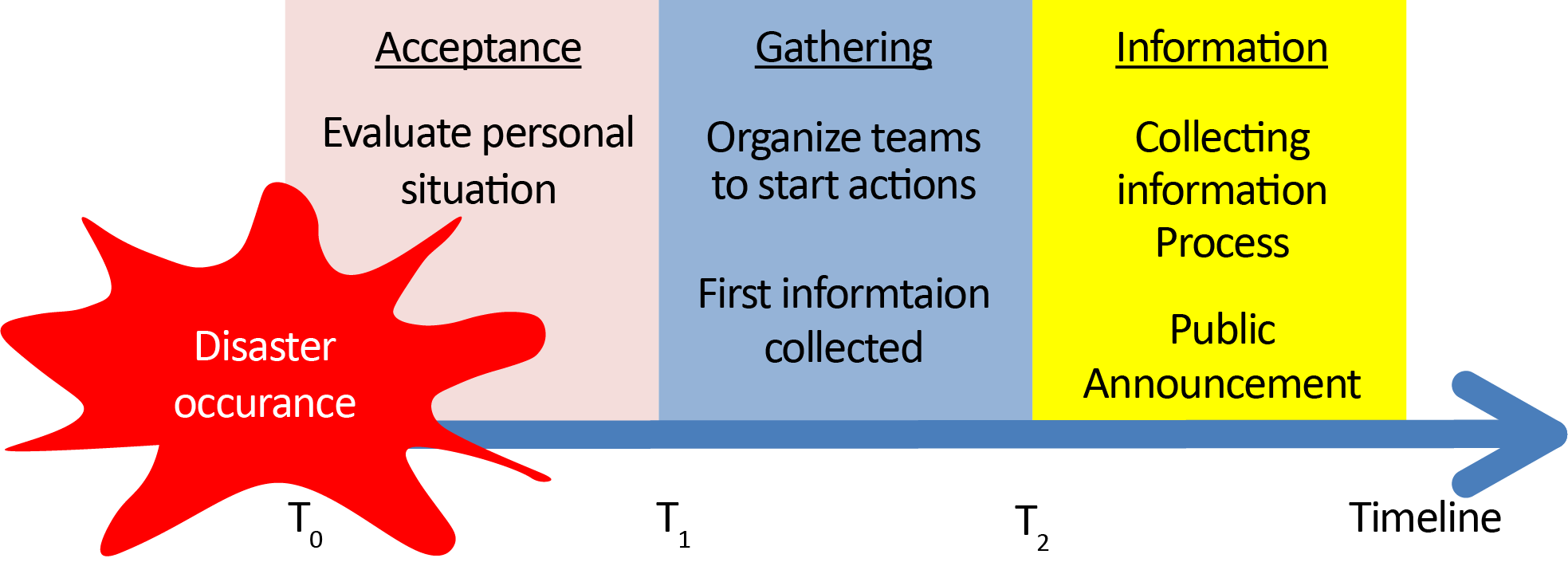

The survey on disaster information sharing and management is a tool that allows an overview of information management during a disaster. The goal of the survey was to collect information management data in the disaster timeline shown in Figure 4.2.2.1. As indicated in Figure 4.2.2.1, the survey was planned from when the disaster occurred, the first response phase and dissemination of the disaster information to the public.

The survey questionnaires related to road administration disaster management focused on the disaster response phase, analyzing current practices among PIARC member countries and others.

The survey included questions on basic information of responders, and questions on disaster information sharing and management practices in their organizations. The survey was based on several key issues to investigate the information management process. In total, the survey included six questions on public information and two questions on technical information.

Figure 4.2.2.1 Role of Information Management in Disaster Management

The survey was sent to PIARC TC members and to South American countries, by the cooperation of DIRCAIBEA (Council of Road Administration Directors from Iberia and Latin America). The answers were received from 19 countries shown in Table 4.2.2.

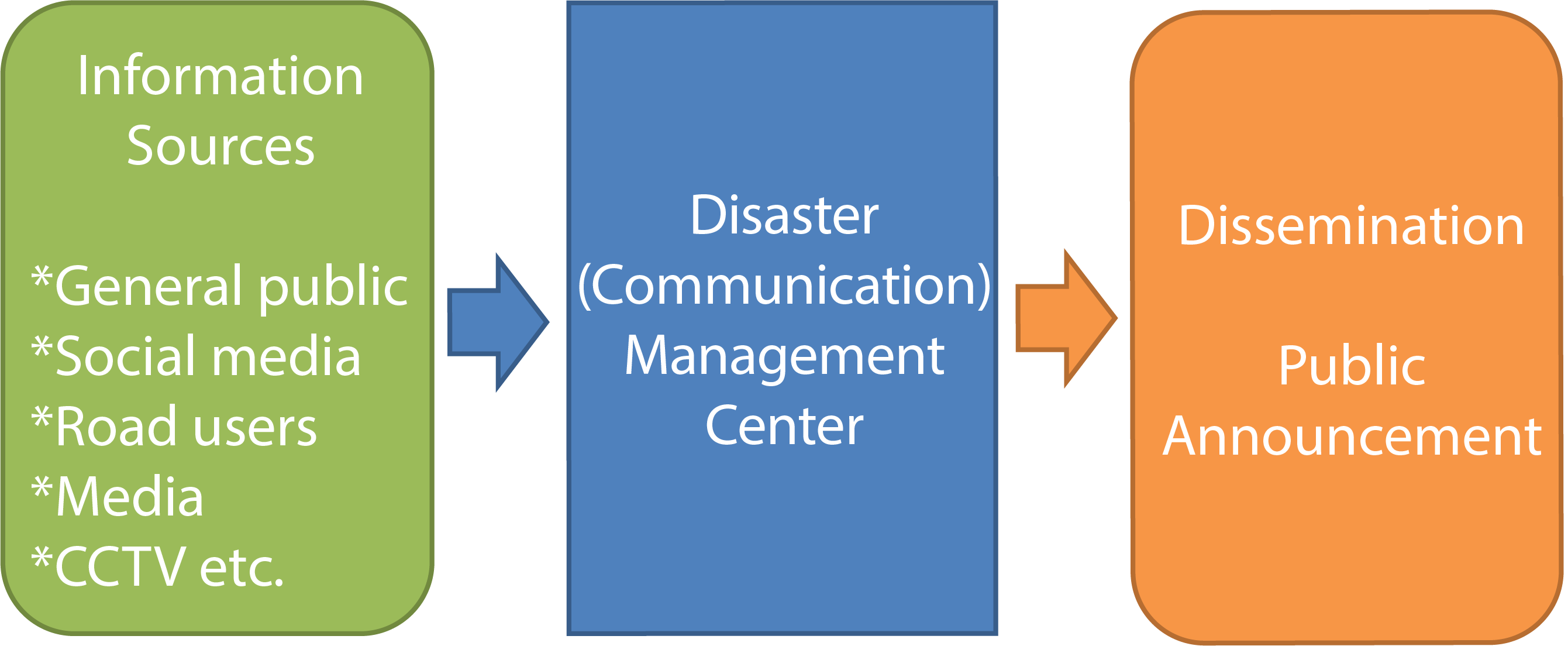

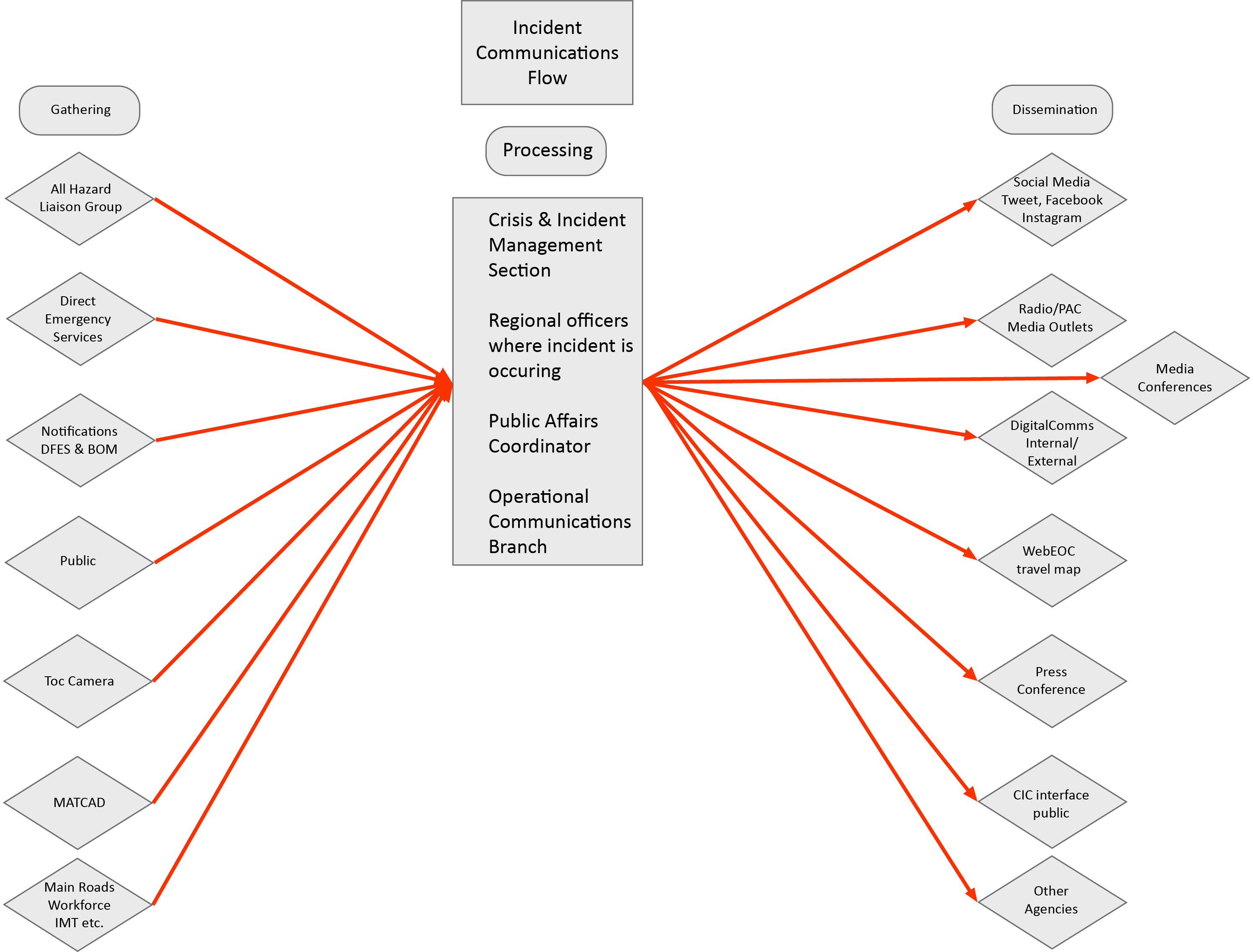

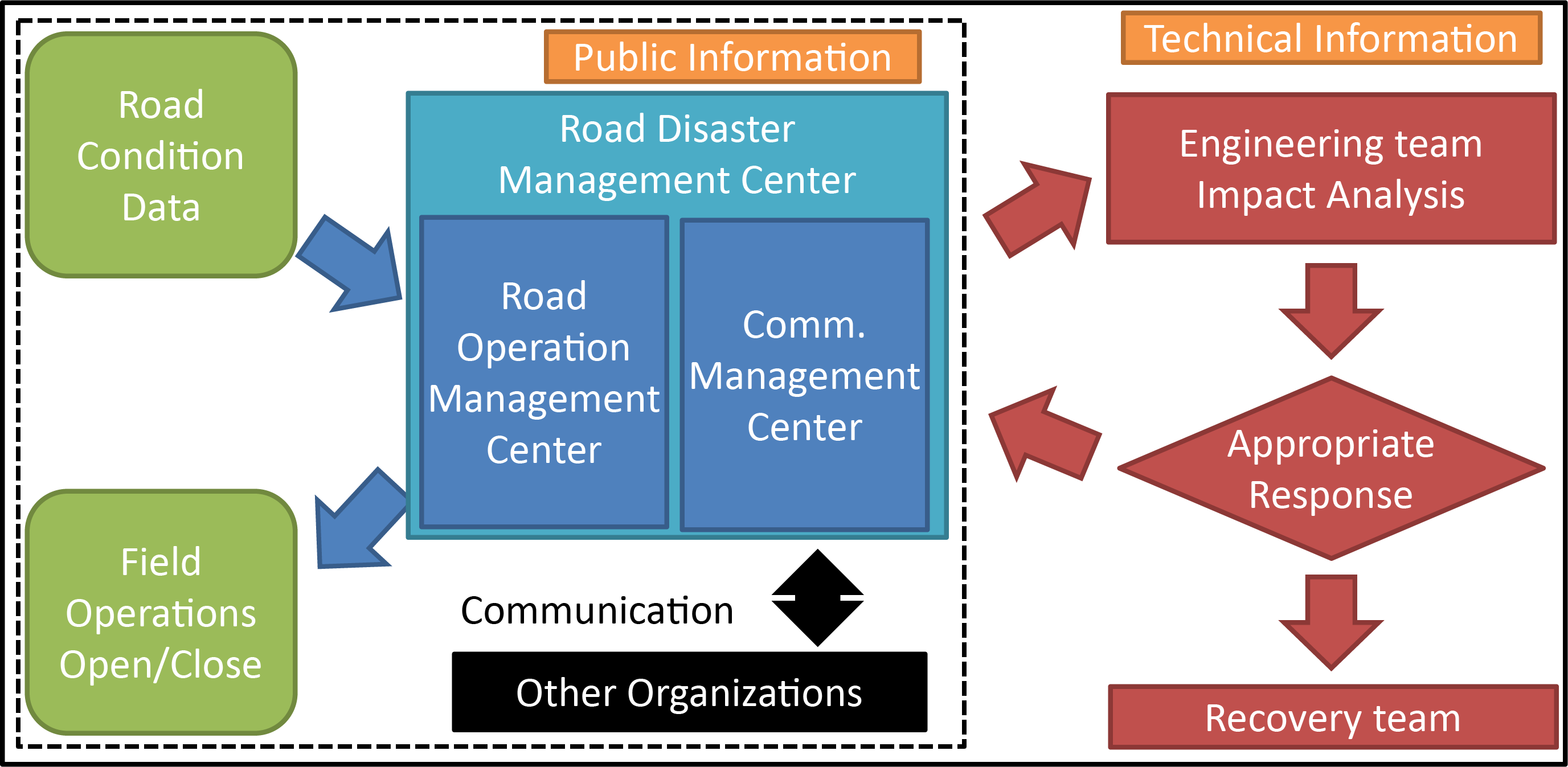

An initial analysis was made to the communication structure. According to the survey results, all of the survey countries have a similar communication structure, composed of collecting information from different kind of sources, managing information and processing information in the management control center, and disseminating and announcing information through VMS or public media. The general communication structure is shown in Figure 4.2.2.2.

| Survey Type | Received | Countries |

|---|---|---|

Survey through TC Members | 13 | Austria, Australia (2), Chile, UK, Japan (6), USA(2) |

Survey through First Delegates | 4 | Canada-Quebec, Denmark, Hungary, Mexico |

Survey through Related Organizations | 1 | Dominican Republic |

Others | 1 | Malaysia |

Total | 19 |

|

Figure 4.2.2.2 The general Structure of the communication flow in case of disaster in terms of public information

Some countries pointed out that the vital role of the disaster management center is not only road operation management but also communication management. One of the main roles of communication management is to coordinate sharing the disaster and emergency information among road organizations, related organizations and road users through internal and external communication. This function is very important but only generic communication plans have been developed in each country. There are few examples of pre-determined detailed communication plans for disasters. Figure 4.2.2.3 shows a typical internal communication diagram between a central communication center and their branch offices in road organizations. Figure 4.2.2.4 shows an external communication diagram from collection of the disaster information to dissemination of the disaster information to the public.

Figure 4.2.2.3 Internal Communication Structure (MEX)

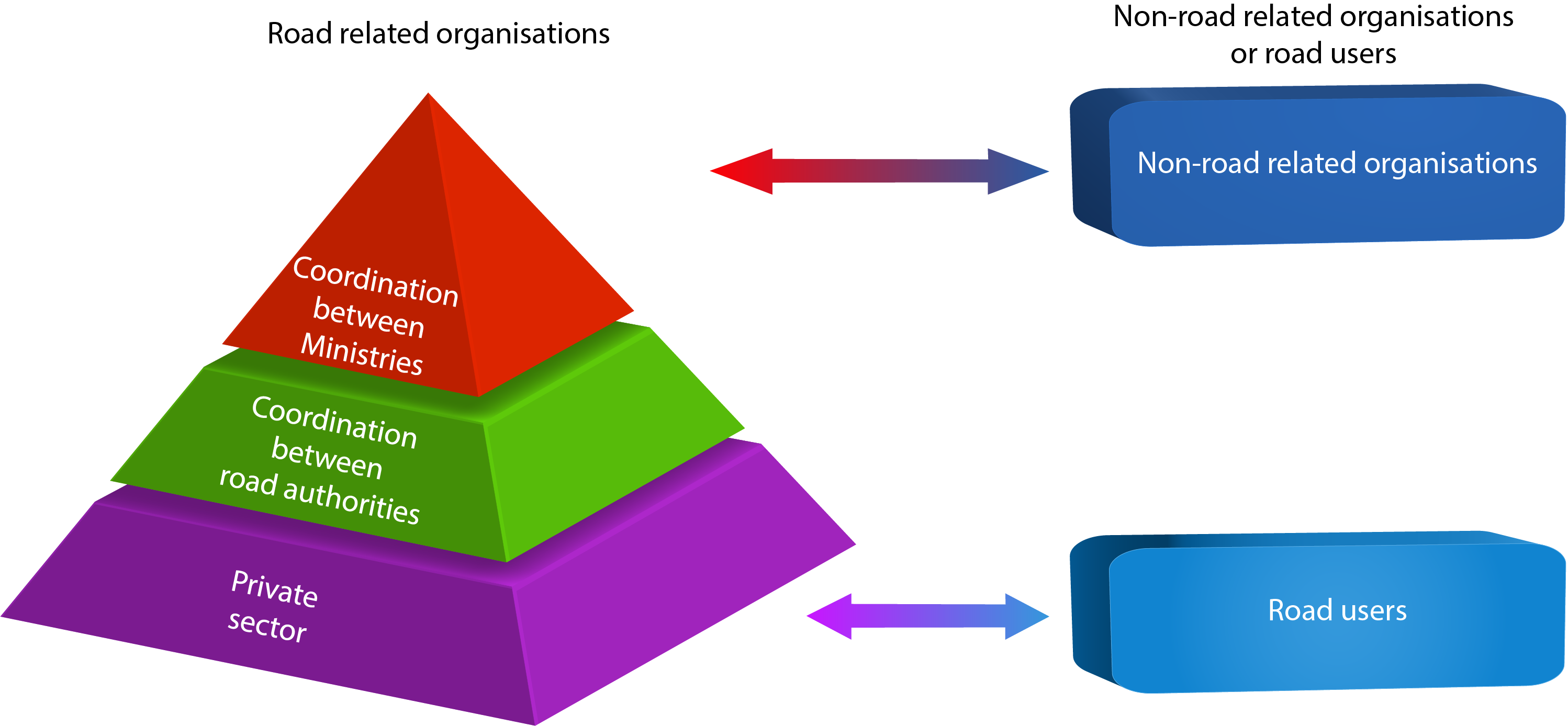

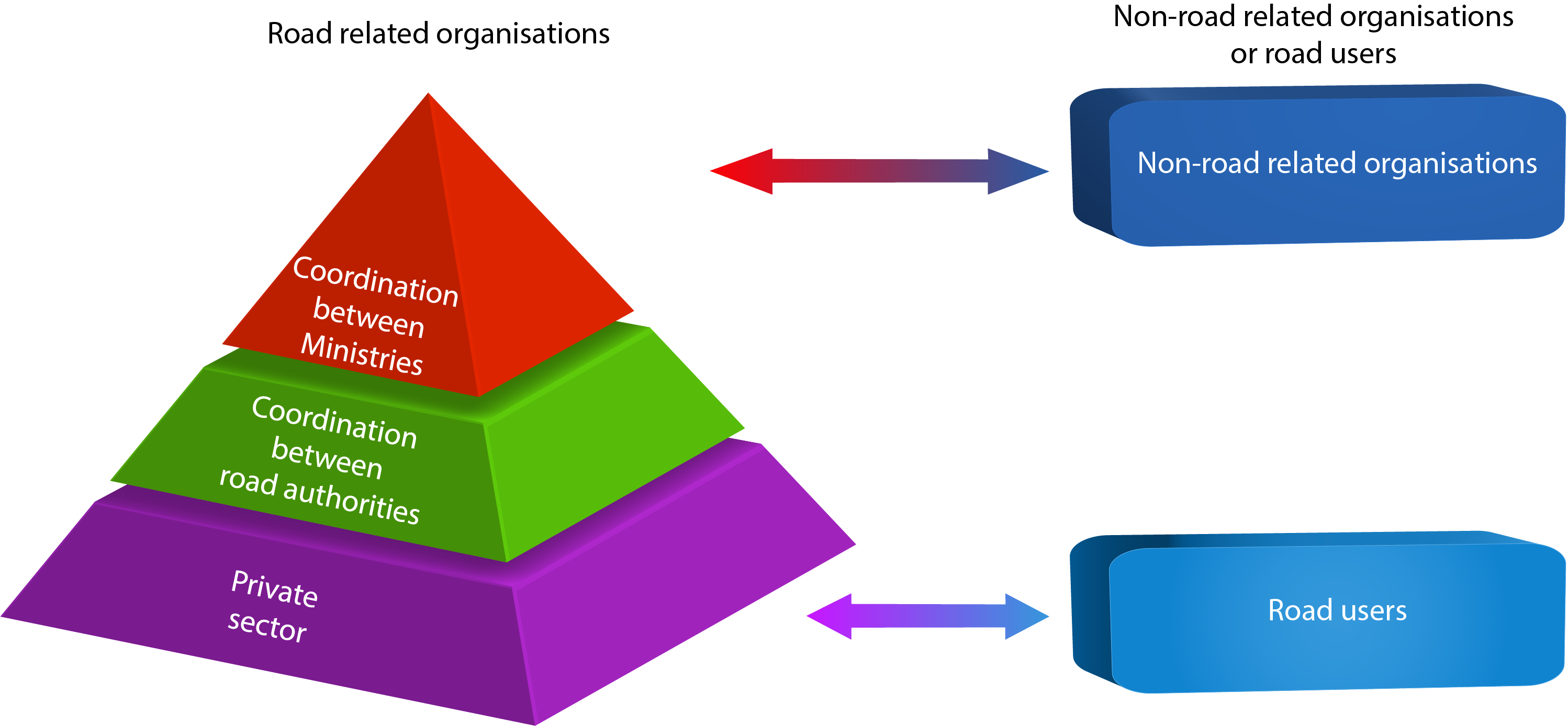

Figure 4.2.2.5, developed in the disaster management study in the PIARC previous cycle 1, indicates the importance of cooperation inside road-related organizations. This figure also shows the importance of communication between road-related and non-road-related organizations. This diagram can also be applied to communication:

According to the findings from the survey, it is identified that enhanced internal communication results in disaster management improvements. To ensure effective communication, daily communication practices are necessary. Coordination with technical specialists and political authorities is also a part of internal communication that is needed for decision making. In order to strengthen such decision-making, clarification of authority and responsibilities, is essential.

Figure 4.2.2.4 External Communication Structure (AUS)

Figure 4.2.2.5 Cooperation Structure

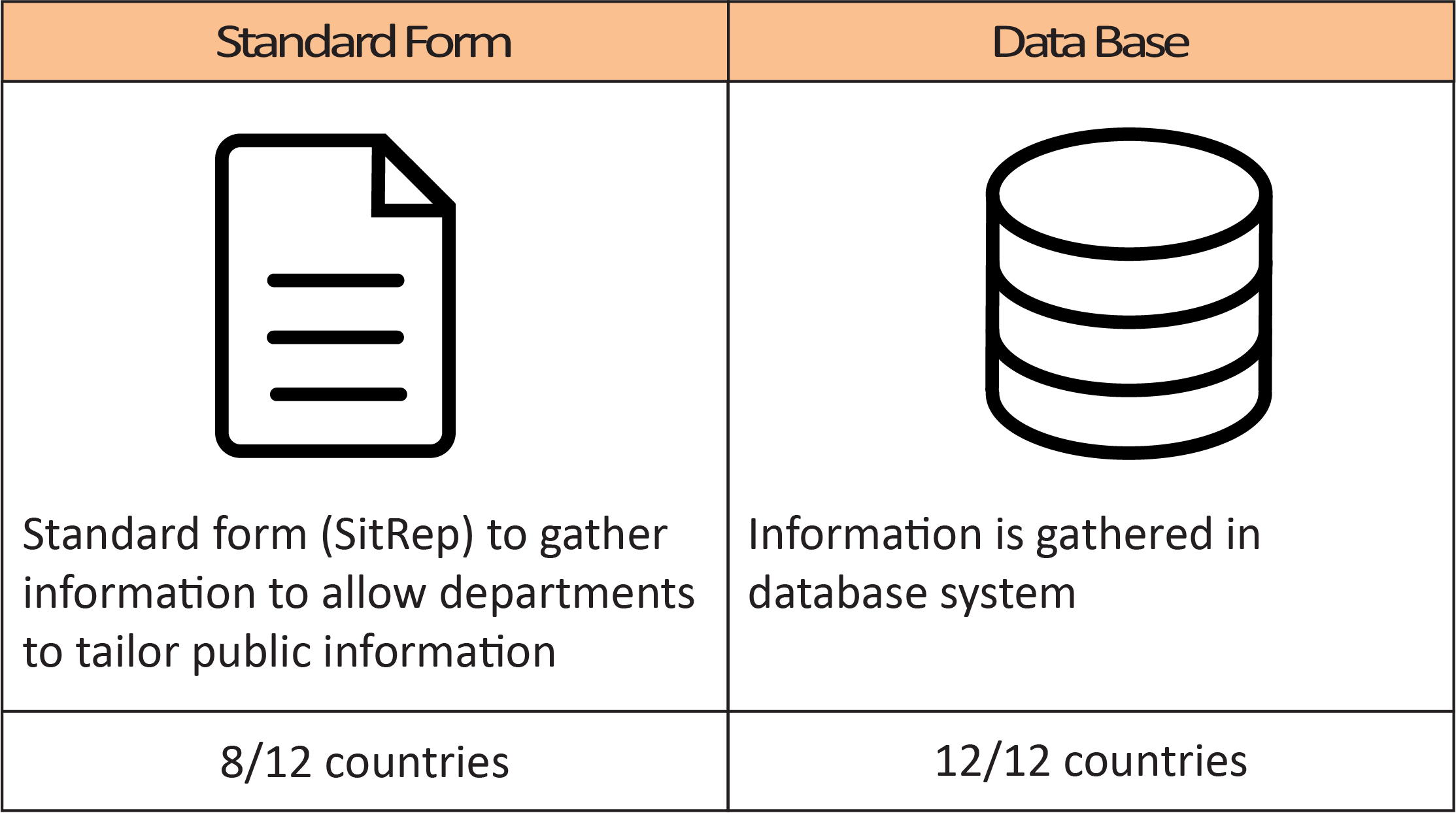

Figure 4.2.2.6 shows the general status of situation reporting. Half of the survey countries have a standard form (SitRep) to report the incident/disaster situation. Other countries reported the incident/disaster situation in free format. Whether the standard situation reports (SitReps) are prepared or not, most countries had developed a database or report system for better disaster response. SitReps are very effective to standardize information and are easy to use but may not be as effective for irregular incidents such as multiple modes of incidents/disasters. However, they are an efficient way of systematizing information and as a backup plan when communications systems are lost. As for free format reporting system, it is powerful to report any kind of incident and disaster, but the quality of the report depends on the skill of the reporter.

Figure 4.2.2.6 Reporting System of Disaster Information

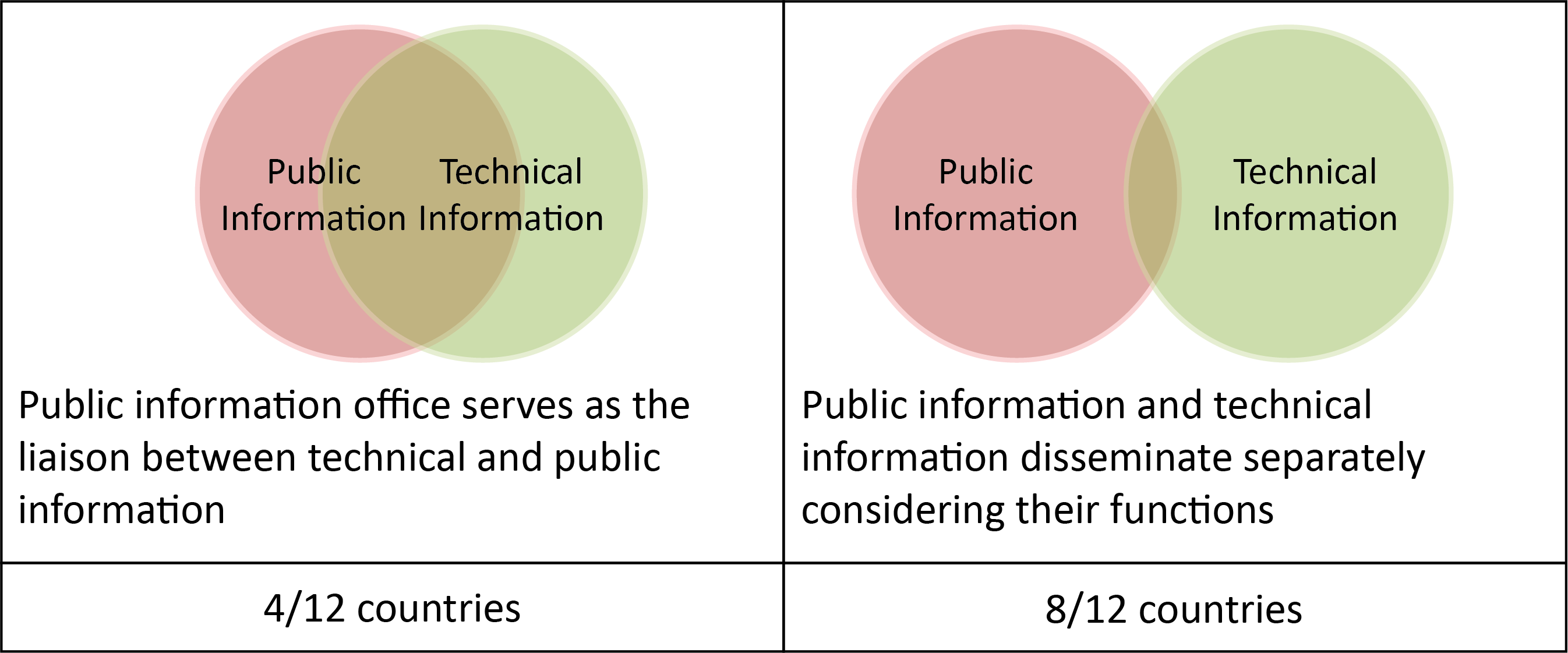

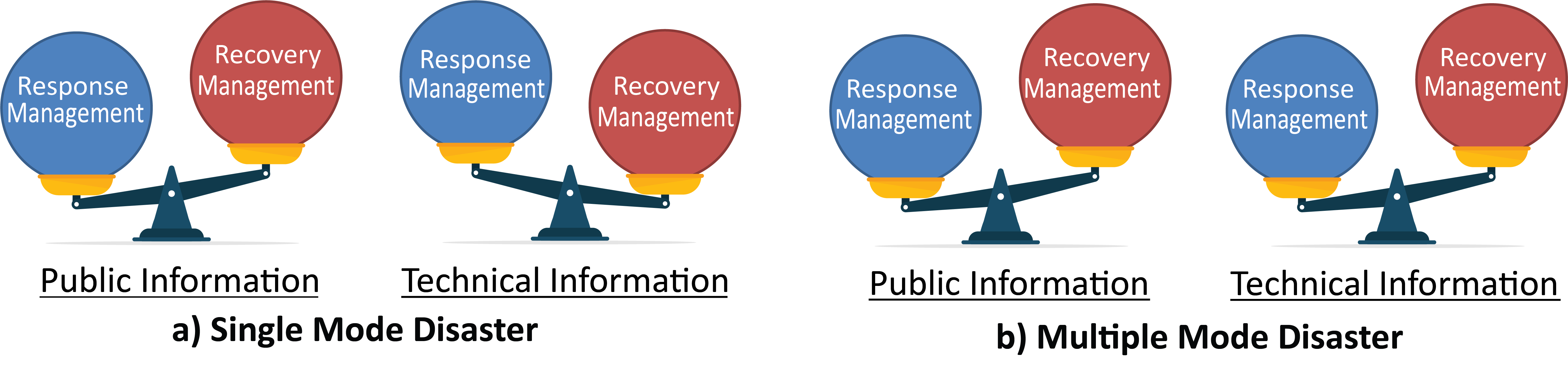

Figure 4.2.2.7 shows the difference between processing public information and technical information. They each have a particular function, therefore pubic information and technical information are treated differently in general. However, some countries tried to link both kinds of information in order to show the technical background to the public.

Figure 4.2.2.7 Public Information and Technical Information

Figure 4.2.2.8 General structure flow of communication in disaster in terms of technical information

Figure 4.2.2.8 shows the general flow of technical information. The collection of disaster information is the same as for public information. The difference is that the technical information is processed by a special engineering team. After the engineering analysis of the disaster, an appropriate response is fed back to the management center. Analysis and synthesis of public and technical information in the management center is required before it is made public, to effectively respond and avoid a secondary disaster.

Generally speaking, as shown in Figure 4.2.2.9, public information is very important to response management, whereas the technical information is very important in recovery management. This is one of the reasons why public information and technical information are treated separately. This idea is effective in management of single mode disaster. In the case of a multiple mode disaster, such as simultaneous multiple disasters or consecutive multiple mode disasters, technical information is also very important in response management, such as earthquake and tsunami, land slide and debris dam, and also heavy rain and flooding. Therefore, linking public and technical information should be considered in disaster management.

Figure 4.2.2.9 Public and Technical Information in Response and Recovery Management

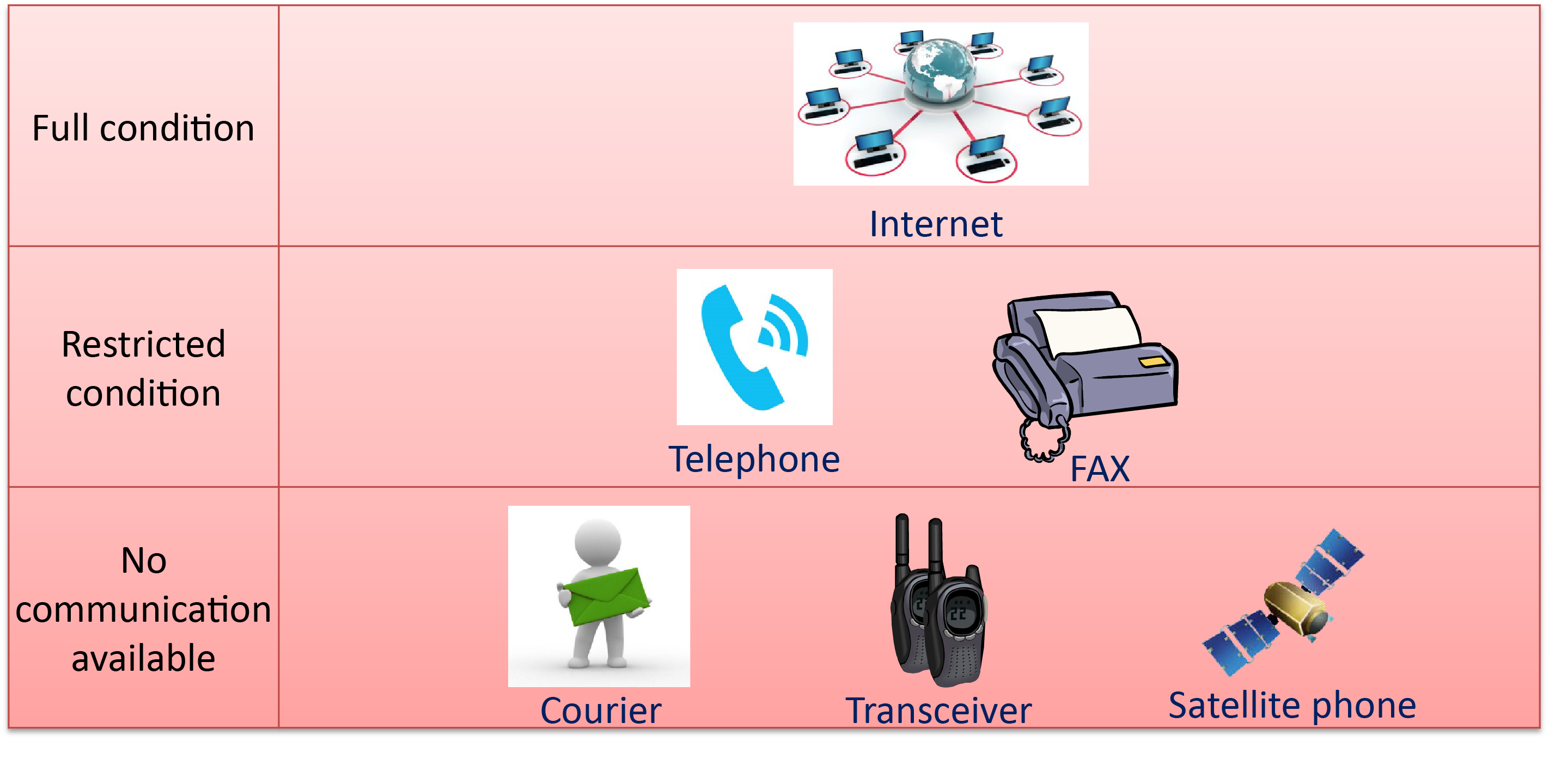

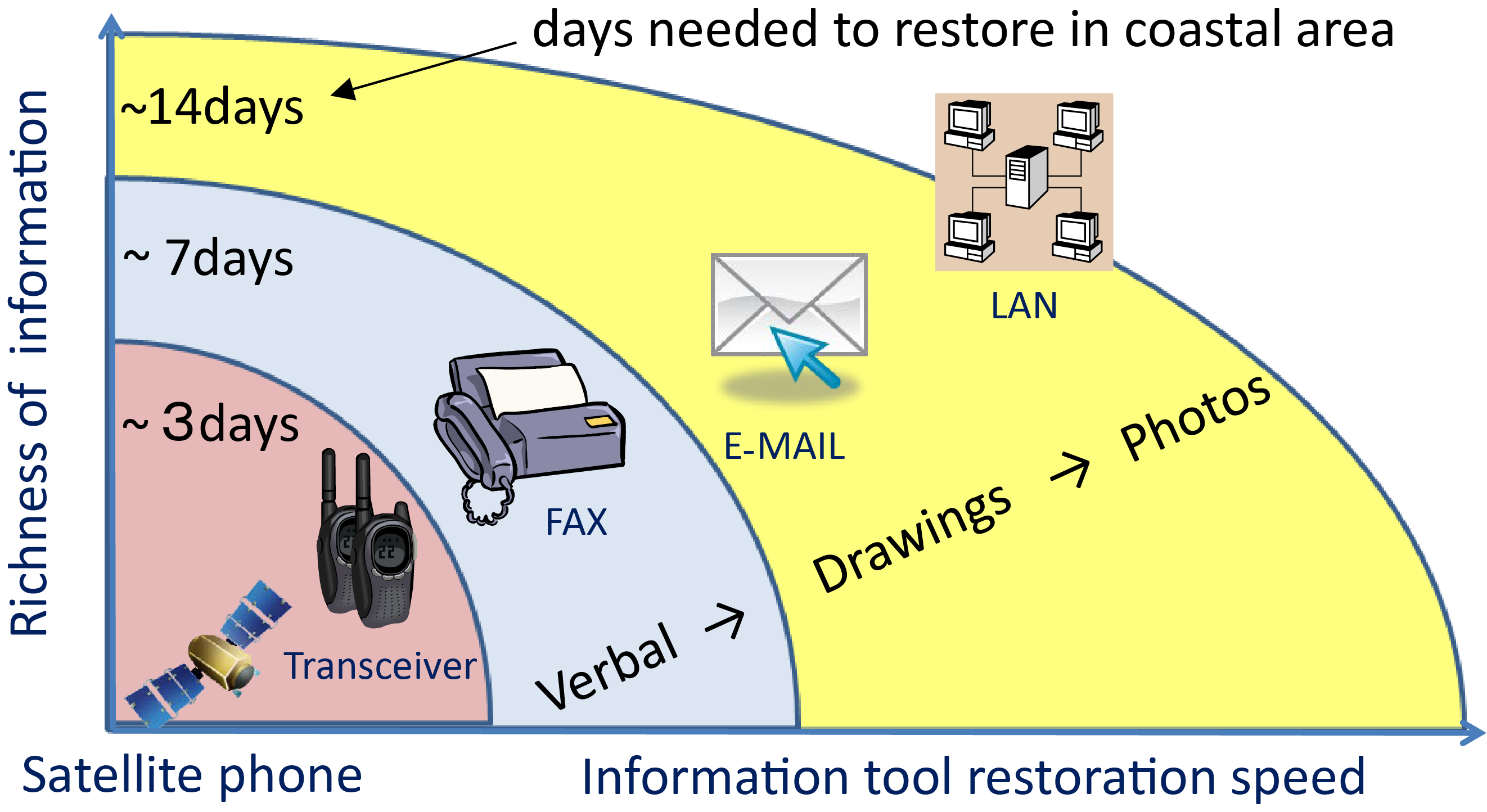

Figure 4.2.2.10 shows the current preparedness of communication tools where communication is restricted. In the survey countries, there are no alternative tools except tools shown in Figure 4.2.2.9. Survey answers in relation to tools used where no communication line is available are varied. This indicates that preparation for the loss of communication lines should be considered.

Figure 4.2.2.11 shows a summary of the communication recovery for the 2011 East Japan earthquake and tsunami. The communication tools recovered gradually from elementary to complex tools. Countries should prepare for communication in this environment.

Figure 4.2.2.10 Preparedness in Communication Tools where Communication is Restricted

Figure 4.2.2.11 Communication Speed with the Recovery of Communication

Communication structure in disasters is a key component of information management. Development of a communication structure is urgently recommended in many road organizations.

Social media and communication technology allow efficient exchange of information. But it can become risky when information comes from several sources and each one has a different interest and goals.

Reliability of information is required in order to inform and not misinform, especially when the population is facing a major disaster.

User information is very fast but less reliable than road agency information, due the requirement to firstly validate it. Preliminary technical information is useful to establish preliminary frameworks for resources and budget.

The importance of backup for complex communication scenarios should be taken into consideration. While information gathering methods that rely on technology are important, it is convenient to have a method for instances where there is a lack of connection.

Media sharing needs behavioral rules, as excessive text or fake images add inefficiency to the process.

During a scenario of full communication, the internet and social media are widely accepted as reliable and efficient ways to transfer data. However, old technology is reliable when a communications restriction appears.

Social media and new technology are changing communication and how information is shared.

Data is transmitted worldwide very fast and to many people instantaneously. But in a disaster, systems or technology could be affected. That is why it is important to establish how to transmit the information in several situations.

Questions in the survey aimed to understand what systems are used as backups in extreme situations.

User information and technical information are different due to their different objectives. What users need is information about connectivity and traffic conditions (average operational status and connectivity) but road agencies need information about infrastructure conditions and damage to establish disaster teams for response.

Technical information about infrastructure damage is more detailed and slower to be obtained. Damage needs to be identified on site or via monitoring technology, and also needs a technical vocabulary that is not always understandable for road users.

This must be considered when you define the ways to share information in multiple mode scenarios, as technical information must be deposited in a database in order to process it and obtain relevant data for planning, but user information is not necessarily useful as historical data as long as users are informed.

Technical information should be standardized and not rely on a particular software package or database, which may contribute to misunderstanding and bad decision making. This will require some training and coordination among road agencies and organizations.

Information management is becoming a key component in disaster management with the progress of internet communication technology. Currently large and important progress can be seen in disaster information management. Conclusions and recommendations are summarized below:

Management of public and users expectations is important in order to try to be clear about what the public and users expect from Roads Directorate and make clear what they will get. So, the goal is to keep users frustration levels low by been realistic with the expectations and make them understand the spirit of the project.

1 Corina Warfield, The Disaster Management Cycle, https://www.gdrc.org/uem/disasters/1-dm_cycle.html

2 2010. Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, EERI Special Earthquake Report, Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, June

3 2011. ITS-Japan, Passable road and road closure map, https://www.its-jp.org/news_info/6568/, March

4 [Example] 2012. UK Cabinet Office, Chapter 7 Communicating with the Public, Civil Contingencies Act Enhancement Program, March

5 2016. Queensland Government, Queensland State Disaster Management Plan, Disaster Management Act 2003, September

6 2015. Tokushima-prefecture, Web document, https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology, February [In Japanese]

1 2016. TC 1.5 PIARC, Risk management for emergency situation, PIARC technical report, 2016R26EN, November

Excellent coordination and cooperation among the parties involved in emergency situations is required for successfully managing these. A legal framework is needed to define the respective responsibilities, key roles and competences of participating entities. Figure 4.3 shows an interrelation diagram of road-, non-road-related and road users in coordinative and cooperative actions in emergency situations.

Clear legal responsibilities covering a range of activities and timeline for emergency management, from planning to restoration of an affected area, is of paramount importance to successful implementation of such framework.

National and local governments, related coordination bodies for disaster management at national and local levels as well as the private sector and road network stakeholders, need to establish a well-defined emergency management system with clear actions to be taken in each stage of the emergency management process: prevention/preparedness, emergency response and recovery/rehabilitation.

Road traffic can be affected from a range of situations, ranging from slight traffic disruptions to extensive disruptions and damages in transportation technology, infrastructure and systems. The consequences of natural and man-made hazards that result in emergency situations are even more pronounced in extreme and complex situations that are defined as crises.

The aim of an organization is to anticipate and adequately respond to emergency situations in the form of contingency planning and by creating the necessary material, financial and human resources needed to address the emergency.

Management of emergency situations consists of institutional and functional components. The institutional component describes the type of emergency situations, the managerial hierarchy and the functionality, competencies, relationships and constraints of the interconnected organizational elements needed to address the situation. The functional component involves a comprehensive set of action plans, experiences, recommendations and measures to be used by organizations responsible for contingency planning and emergency situation management.

Figure 4.3-1 Interrelations of road-, non-road-related and road users in coordinative and cooperative actions in emergency situations

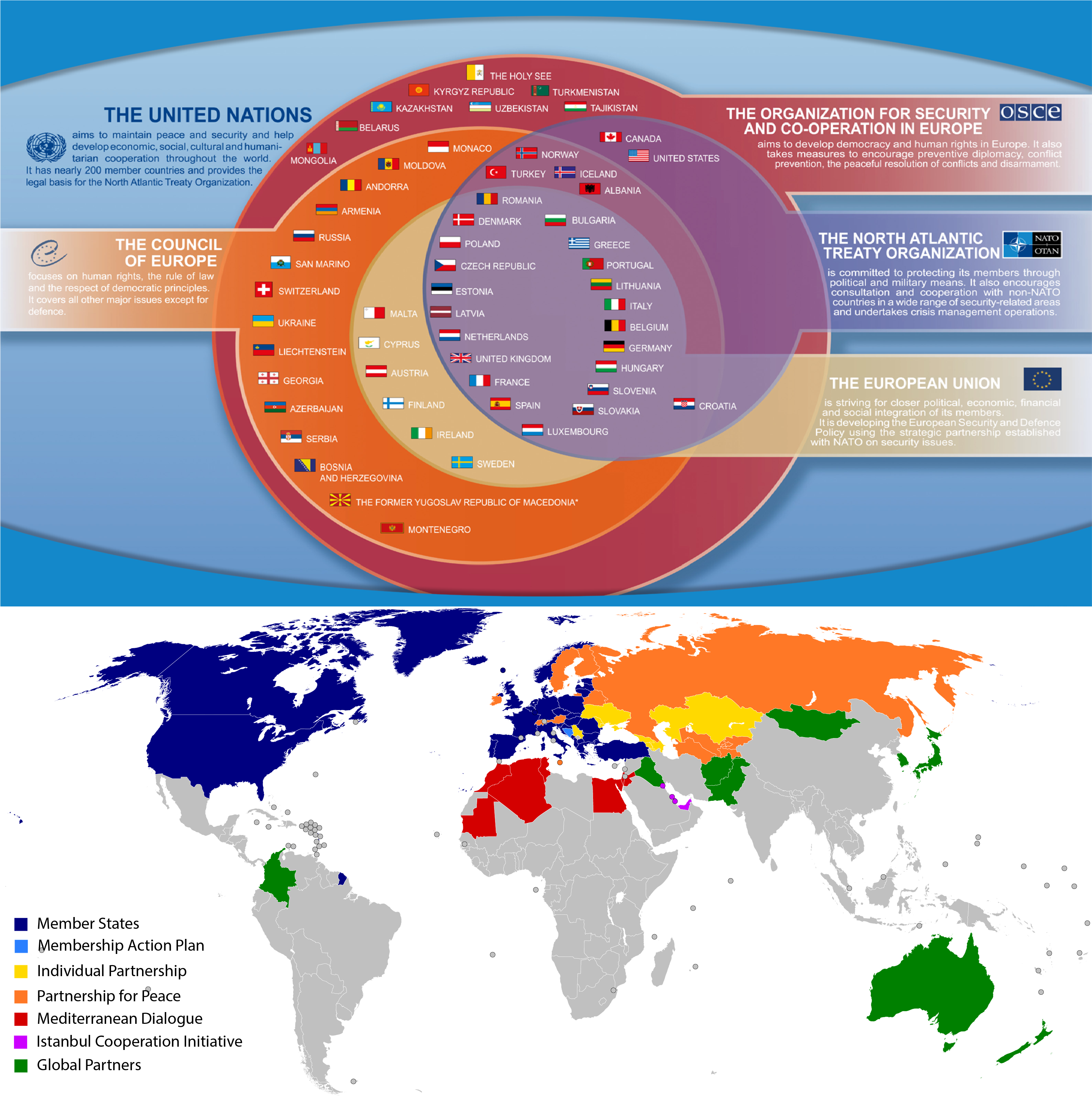

Safety is ensured independently, but also in close cooperation with various international organizations, the signatory and regulatory agreements of which are binding on Member States.

NATO is an example of an intergovernmental organization with shared values, a common determination to defend them and with available resources and measures that provide the capacity do so whenever and wherever necessary. NATO cooperates with governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

With the need for greater solidarity in today’s security environment, NATO´s Partnership policies have been steadily extended with a view to build closer and more effective relationships with numerous countries and international institutions. This involves enhanced cooperation on civil emergency planning, including the possibility, in case of disaster situations, to request the assistance of the Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Center (EADRCC), which is based at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, Belgium.

The EADRCC was established in 1998 and is a partnership instrument open to 69 countries. Its role is limited to coordination of allied and partner nations’ assistance to each other in case of natural or technological disasters and acts as a focal point for information sharing. It works closely with the relevant United Nations (UN) and other international organizations that play a leading role in responding to disaster situations for which it also offers liaison arrangements such as between the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Action (UN-OCHA) and the EU. A permanent liaison officer from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs is assigned to the EADRCC staff.

Since its foundation, it has received more than 60 requests for international assistance for crises concerning earthquakes, floods, forest fires, mudslides, storms, extreme weather, pandemics, tsunamis, technological disasters, humanitarian emergencies, assistance to massive events (e.g. assistance to Greece during the Olympic Games), hurricane Katrina and Pakistan monsoon floods among others.

EADRCC can also address crisis situations in Partner countries, the wider Mediterranean region, the broader Middle East and in ‘contact countries’ such as Japan, Australia, Pakistan and China. EADRCC closely cooperates with other international organizations such as the European Union, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and the United Nations (see Figure 4.3.1). These policies have put the spotlight on the major contribution to international security that strengthened cooperation can offer.

The Centre has developed state-of-art operating procedures to ensure rapid responses in emergencies and encourages participating countries to develop bilateral or multilateral arrangements to address issues such as visa regulations, border crossing requirements, transit agreements and customs clearance procedures that can delay channeling of rescue aid to a disaster location.

The EADRCC organizes regular major disaster training exercises in different participating countries designed to practice procedures, provide training for local and international participants, build up interoperability skills and capabilities and harvest the experience and lessons learned for future operations.

Figure 4.3.1 Interrelations of NATO with other international organizational bodies

The National Security System provides the organizational and regulatory framework for cooperation and coordination in emergency situations.

A National Security System can be defined as a system of administrative authorities, local governments, armed forces, emergency services, legal entities and individuals, and their relationships and activities. The scope of this system is to ensure a coordinated approach to enable fulfillment of basic obligations of the state in securing sovereignty and territorial integrity, and in protecting democratic principles, life, health and property of the population.

The National Security System is designed to comply with the Constitution and its essential elements are constitutional bodies and institutions. Ensuring security is based on a comprehensive approach, which includes designing appropriate mechanisms for managing risk or crisis situations and properly planning for related needs.

The National Security System serves as the institutional framework in creating and implementing related policies and is composed of physical and legal entities. Its basic function is the management and coordination of the various organizations responsible for national security interests. In creating a National Security System, political, military, economic, financial, legislative and social factors need to be accounted for effective risk management. Interactions and relationships among these factors need also to be defined for determining the responsibilities and obligations of the different organizations.

Such structure usually includes the President or Head of State, Parliament, Government, National Security Council and its working bodies, the Central Administration, regional and municipal authorities, the Armed Forces, Intelligence Services, rescue services, health and emergency response services. The Government is responsible for formulating basic policies, strategies and guidelines for disaster reduction and for securing coordination of government disaster reduction activities. Ministries and Agencies have responsibility to take actions related to disaster reduction within their own mandates. A Supreme Executive Authority is responsible for managing and operating the entire security system.

Creating a national security system is a long and difficult process. Legislation is required to define the purpose of individual entities and determine their interactions and obligations to civic life in the law-making process. Legislation often plays a decisive role in emergency management as it affects all stages involved in emergency situations.

A functional security system is not only a tool for effective crisis management, but also enhances prevention of- and preparation for potential crises, their early identification and warning. It is an open and dynamic system, as it must constantly respond to changes in the security environment and emerging threats. Building experience and developing economic and financial viability in such systems is a long-term and arduous process involving both systematic training and real-case experience.

Security measures involve ensuring defense against external military threats, protecting internal order and security, safeguarding the economy and protecting the population from the effects of natural and man-made disasters, including violent social conflicts. Experiences from developed countries clearly indicate that the aforementioned issues are interconnected and need to be addressed on a common basis when planning related measures.

In addressing major emergency situations, we can identify three levels of coordination based upon the magnitude of the emergency:

These levels involve strategic, operational and tactical components of coordination and cooperation but are also emergency management stage-specific. Integrated Rescue System (IRS) provides a framework for efficient use of resources and cooperation capabilities in emergency situations. Next, the IRS and the different levels of cooperation and coordination are described.

IRS is an effective system of links, rules of cooperation and coordination of rescue teams and security forces, state and local governments, individuals and the private sector in the implementation of common rescue and relief work and in the preparation for emergencies.

IRS aims, while taking into account the legal framework, in integrating and combining every available material and human resources to perform rescue in the most efficient and economical use. An IRS is not an organization in the form of institutions, but above all an expression of rules and cooperation.

The components IRS are divided into the following:

The strategic level for coordination and cooperation lies basically within the government and its supreme leader (e.g. Prime Minister). The government defines the strategic directions in security matters and addresses challenges by forming national plans and programs that are subsequently further elaborated within regional and local governmental units to reflect local particularities. The emergency management process is competed when road users and the private sector are included in the risk management framework.

As the primary concern of emergency management is protection of the population, usually the supreme government authority responsible for the strategic level of coordination is the Ministry of the Interior, which controls the emergency response services and the security services (i.e. fire department, police) or other specialized agency created for emergency management.

For the road transport sector, the relevant authority it is usually a ‘Department of Transportation’ type of body responsible for dealing with emergencies affecting the road network. A permanent working body in the Government, whose members are the highest representatives of the authorities and ministries ensures interministerial coordination and cooperation in the development of strategic plans and policies for emergency situation management. Its main task is to participate in the creation of a reliable national security system and fulfill international obligations. Experts from different sectors (e.g. representatives from the private sector or academia) can supplement such committees to ensure high quality of decision-making in determining appropriate course of action.

Various goal-oriented working committees focusing on individual areas of security are working at a national, regional and local level, to ensure co-ordination in preparation for disasters and crisis situations in their area of competence. These, are usually presided by the highest elected representatives of members if the cabinet, regions, cities and municipalities.

For emergency situations of national implications, a national risk management working body is formed for emergency situation management. Primarily, elected bodies and senior management, especially from national and regional levels, ensure the coordination at the strategic level.

Coordination at the operational level is implemented at all levels concerned with the use of various forms of business operations and information centers that coordinate rescue system components.

Operational management is usually carried out in specific organizational structures tailored to deal with temporary tasks. Such structures have more narrow and focused expertise based on the skills and experience of the individual team members. Actions are more random and follow tested practices under normal operating conditions. This implies that these teams strongly relate on individual initiative and leadership and often improvise to solve ad-hoc problems.

Care must be applied to maintain continuous communication between the working groups and the control center, which should be located in a structure, which enables proper guidance in managing the emergency situation without being hampered from the situation. Organizing such special-purpose structures for emergencies must take into account weather conditions, light conditions, supplies and the protective equipment that should be used due to the risk environment in which work tasks are performed. These working groups should not be logistically restrained when operating under adverse circumstances.

Streamlining the procedures involved in emergency situations calls for the application of modern management techniques and process automation in order to minimize errors and conserve a logical sequence of individual activities. Methodologies must be clear and suit the competences of the operational taskforce. Using data processing methods that take into account the stochastic nature of natural phenomena and allow for temporal analysis of data obtained from road networks is possible to record the sequence of the management process. Follow up and post-event derived lessons are essential in developing integrated methodologies that properly account for the needs of emergency situations and provide adequate logistic support.

Support centers can be established to provide coordination of activities and information exchange and sharing on the status of the emergency situation among the entities involved in management of emergency situations. Private or public entities important for maintaining the operation of the state such as lifeline utilities are often required by law to possess business continuity plans, contingency plans and emergency preparedness plans to ensure operational continuity of services and entities involved in emergency management.

Permanent operational centers are often crucial in resolving the crisis. These, constitute links between public and private sector organizations, including NGOs, and provide information support and resources to all factors involved in emergency management, particularly at regional and local levels.

Cooperation and coordination with the private sector and NGOs is provided mostly at the regional and local level where their knowledge specific to the environment of the affected area comes highly in use. Representatives of these organizations are actively integrated into taskforce teams especially at local or regional levels.

Other cooperation involves active participation and assistance in dealing with the consequences of disasters of organizations that are not directly related to the maintenance and repair of roads and highways, such as automakers and navigation device manufacturers.

At the tactical level, coordination involves mainly relating resources and teams deployed directly on the site of an emergency (e.g. fire brigade, army, police, health services, etc.).

An effective system of links, rules of cooperation and coordination of rescue and security forces, state and local governments, individuals and the private sector in the implementation of common rescue and relief work and preparation for emergencies is an integrated rescue system.

Principle of integration lies in the fact that each source - material and human, but also legal, combine to perform rescue or disposal, to their most efficient and economic use.

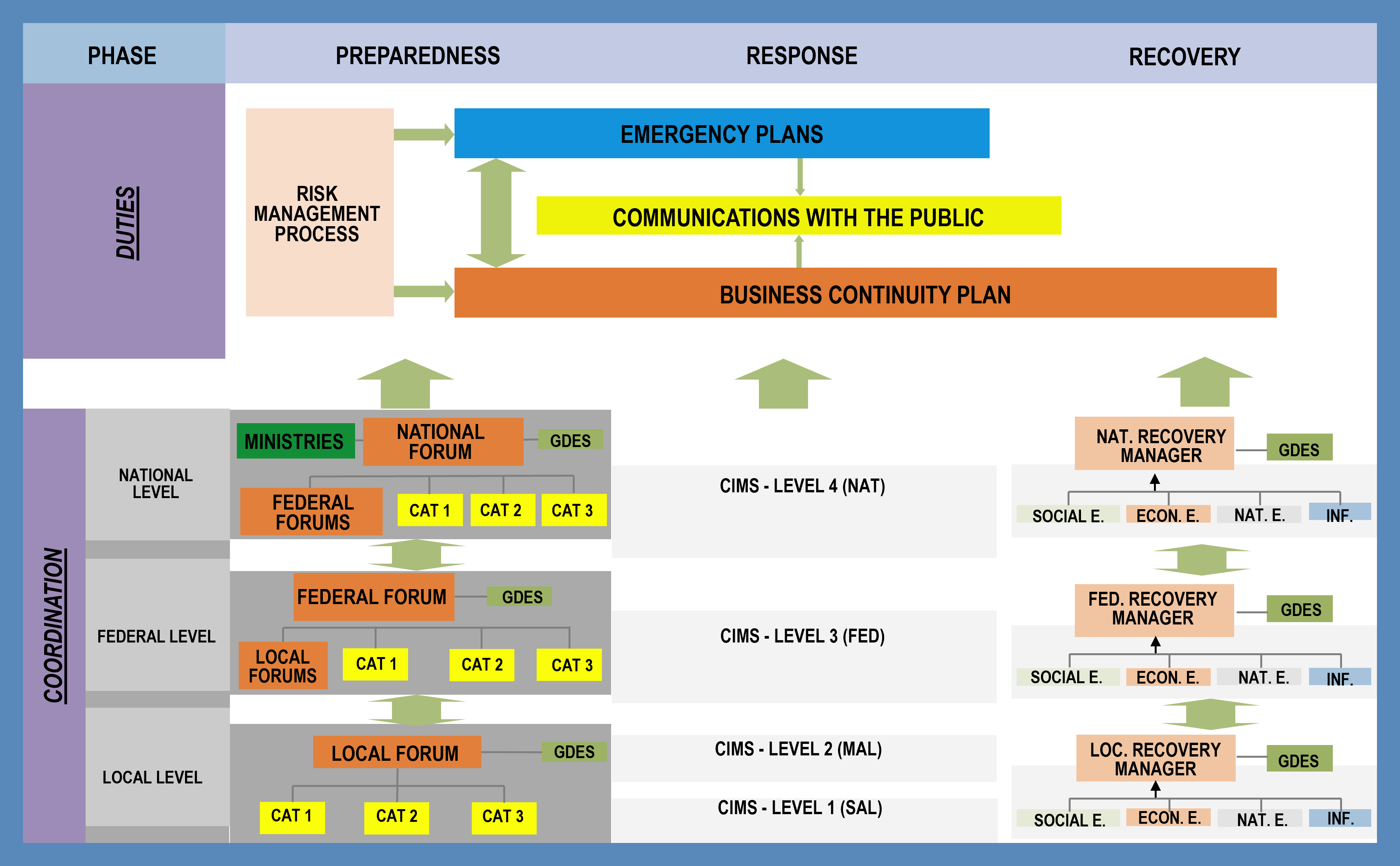

The three (3) stages of the emergency management process (preparedness, response and recovery) imply differences in the coordination and cooperation process. The following description aims to provide a generalized framework of practices observed in countries that are considered among the most advanced in terms of emergency management for each of the three stages.

The organizations implicated at each level of coordination (national, regional, local) can be distinguished into those that are core to the emergency management process (Category 1 – e.g. civil protection, local authorities, etc.), those that assume a supporting role (Category 2 – e.g. lifeline utilities agencies, transportation, etc.) and those that are auxiliary and can be used on a per case basis (Category 3 – e.g. volunteers, NGOs, etc.). Usually, in an emergency, the road sector belongs to the supporting organizations.

Resilience forums (national, regional and local) composed from representatives of all parties involved in this stage can be established to ensure appropriate coordination and cooperation. To facilitate two-way communication and information sharing between Category 1 and 2 responders and central government, standing members of the local resilience forums can form General Divisions for Emergency Situations (GDES) offering advice and encouraging cross-boundary working and sharing of good practice at all levels of coordination 1.

A coordinated incident management system (CIMS) 2 is proposed to ensure proper coordination so that:

The CIMS is composed from four (4) elements: Control/Management, Planning with data collection and analysis, Operations and Supplies. According to CIMS, the first responder to the emergency site assumes the management role. Emergency situation management transition is performed according to predetermined procedures.

CIMS is followed at the three levels of coordination with an inclusion of a sub-level at the local level according to whether multiple agencies (MAL) or a single agency (SAL) are involved in the emergency response.

The recovery stage constitutes a restoration of the quality of life of a community after an emergency situation. Recovery from an incident is unique to each community and depends on the amount and kind of damage caused by the incident and the resources that the jurisdiction has ready or can quickly obtain 3. Recovery is managed with logic similar to that of the Preparedness stage. For determining who is involved in the recovery stage one needs to examine the impact of the disaster in the following four elements:

Task groups from each of the affected environments and sub-task groups specific to the emergency situation need to be formed at all levels aiming to:

A recovery manager (REC. MANAGER) coordinates these task groups. Respective GDES groups can facilitate information sharing and communication.

Figure 4.3.7 shows the coordination structure for the different levels and stages of the emergency management process.

Figure 4.3.7 Coordination structure for the different levels and stages of the emergency management process.

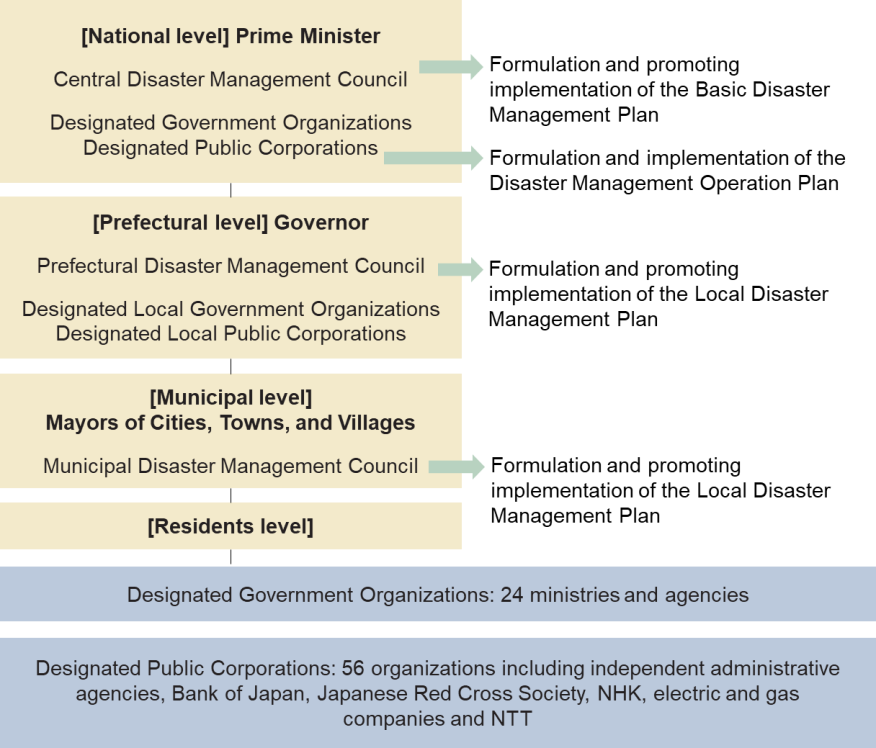

Coordination and cooperation are crucial for effective disaster management since a wide range of organizations, such as national government, local government, highway companies, contractors’ association, consultant association, and other related organizations are engaged in preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery activities 1.

Hurricane Katrina exceeded the disaster response capabilities that had been built up and caused a regional catastrophe. Hurricane Katrina caused difficulties in coordinating communications, security, evacuation, and supply systems in response to a major hurricane disaster, eventually leading to the collapse of command systems and widespread confusion and disasters. Based on this experience, disaster response was reviewed under the "all-hazards approach" in disaster preparedness and response, including the scale of the disaster, sharing of the expected disaster with the population, continuity of government operations, mass evacuation, and security issues 2, 3. Particularly noted was the need for better coordination between the federal government and other response teams. For many of the team members, responding to a disaster is a secondary task, and they had never met each other before Katrina and had not trained together before the disaster. As a result, the response team functioned more like a loosely organized group than a well-trained rapid response team. The importance of cooperation and coordination among the parties involved was pointed out.

In the 1995 Hyogo-ken Nanbu Earthquake, an unprecedented seismic disaster occurred, and the affected areas were devastated. In a large-scale disaster, support from outside the disaster area is indispensable, and this was recognized in the case of this earthquake. In response, many infrastructure managers have signed disaster agreements with related organizations on a nationwide scale to strengthen their cooperation in the event of a disaster. They have also signed agreements with the Self-Defense Forces for emergency response, with construction industry associations and consultant associations for emergency response, and with local governments for a wide range of cooperation, from regular maintenance to emergency management. In recent years, even closer cooperation systems have been established with local governments. In Japan, the spearhead of disaster response is the local government. In recent years, liaisons, TECH-FORCE, and recovery agents have been established to support the local governments in their tremendous work, and a system has been built in which all related organizations work together to respond to and recover from disasters. Ishiwatari has written in detail about these cooperative systems.

Regardless of the various triggers, it is important to enhance the cooperative system between the national government and local governments, government agencies and expressway companies, and other organizations. Figure 4.3.8 4 shows the outline of Japan’s disaster management system as an example of the disaster management system.

Figure. 4.3.8 Outline of Japan’s disaster management system

1 2012. U.K. Cabinet Office Emergency. Emergency Response and Recovery, Fourth Edition. July.

2 2005. NZ Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management. Coordinated Incident Management System (CIMS).

3 2008. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. National Response Framework, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Washington DC. January.

1 2020, Miko Ishiwatari, Institutional Coordination of Disaster Management: Engaging National and Local Governments in Japan, Natural Hazards Review, 2021, 22(1): 04020059, December

2 2008, Jack Pinkowski et al, Disaster Management Handbook, CRC Press

3 2006, Wells, J., Catastrophe Readiness and Response, (Paper Presentation) The Emergency Management Institute (EMI), 9th Annual By-Invitation Emergency Management & Homeland Security/Defence Higher Education Conference, National Emergency Training Center, Emmitsburg, Maryland, June

4 2014, Federico Ranghieri and Miko Ishiwatari, Learning from megadisasters -Lessons from the great east Japan earthquake, pp73, the world bank, January

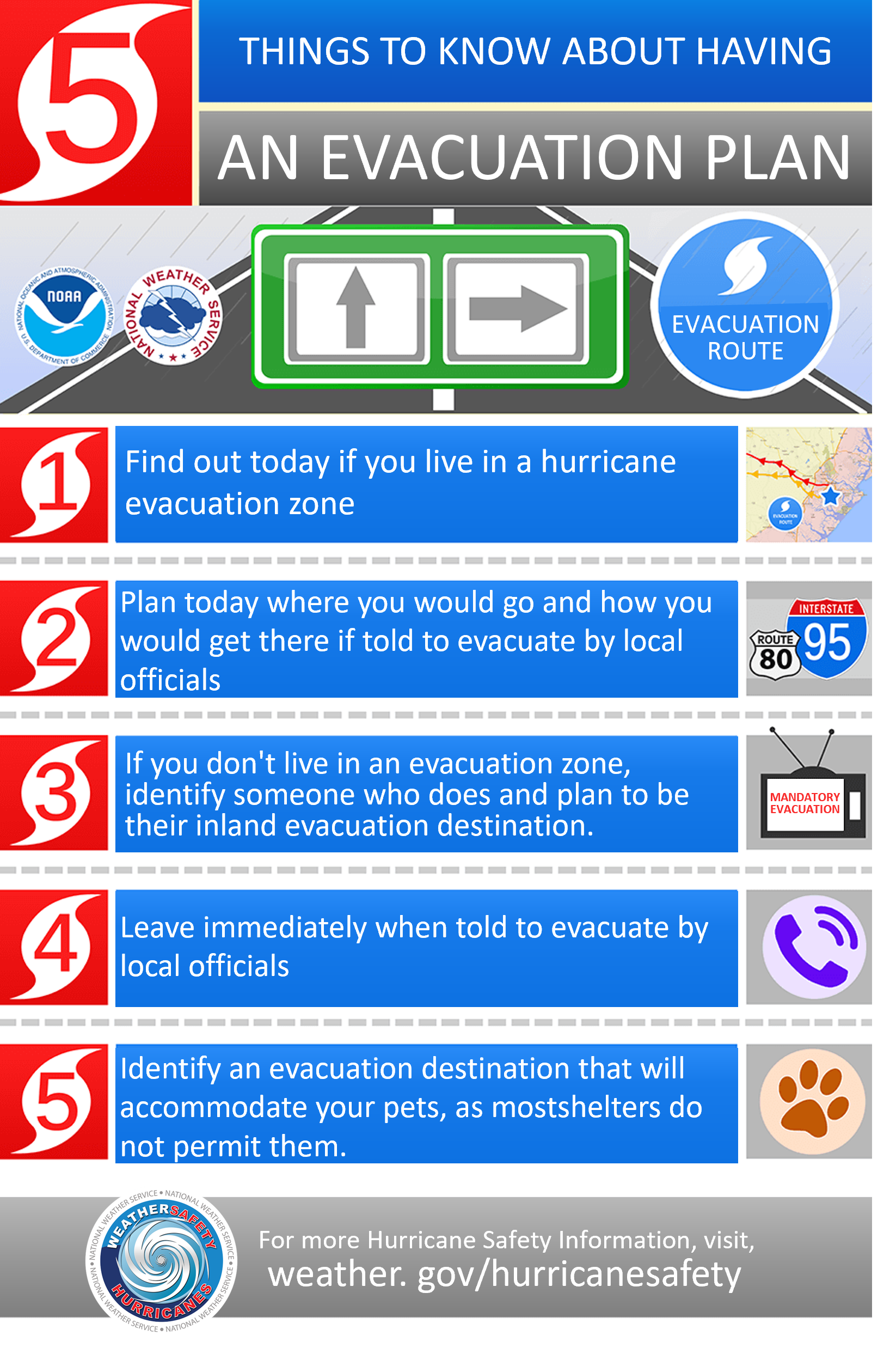

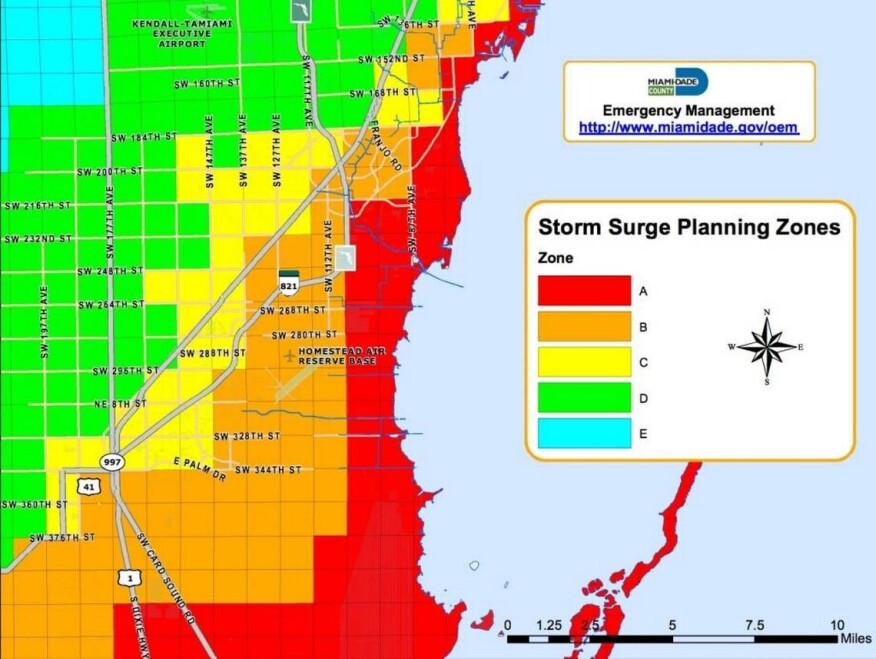

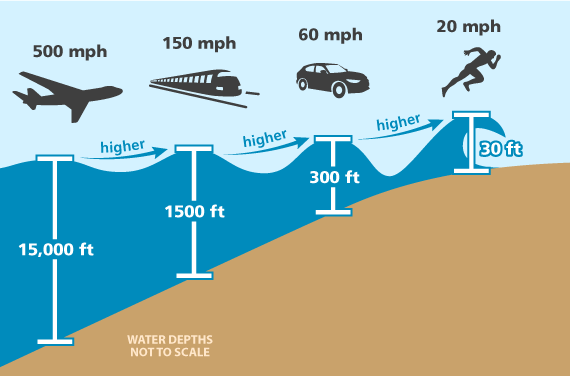

Evacuation planning has become a critical component of disaster management operations in recent years. Each year, millions of people around the world are affected by evacuation orders due to the increasing frequency and severity of natural disasters (Figure 4.4), along with periodic industrial/technological incidents and malevolent/terrorist activities.

Figure 4.4 Houston residents evacuate due to imminent threat of Hurricane Rita

These disasters teach us the importance of planning, coordinating, and executing evacuations as a primary protective action regardless of the threat or hazard. The challenge is to quickly identify the appropriate level of action necessary to address a variety of factors, including the community’s demographics, infrastructure, resources and authorities.

The primary authority and responsibility for evacuation typically begins with the local government working in conjunction with the community. Prior to an incident, jurisdictional governments should engage with public and private sector partners, nongovernmental organizations, faith-based organizations, and individual community members so there is an understanding of the roles and responsibilities of each partner along with the authorities and limitations that exist.

Evacuation orders are issued by the jurisdictional authority. This authority will also manage traffic flow, identify evacuation routes, and consider any necessary respite site needs if food, water, and fuel availability is limited.

Clear and concise messaging, in multiple accessible formats, is critical in order to actively engage citizens in the event of a voluntary or mandatory evacuation. This will include static and dynamic signage, social media, public emergency alert systems, and other available resources. Messaging should be pre-approved by the appropriate jurisdictional authority and advise the public of necessary actions, including the specific threats or hazards impacting their community. It is critical that authorities continuously monitor social media during the event to identify any contradictory statements and attempt to correct inaccurate accounts of the situation.

Public awareness of the hazard, of evacuation procedures, and especially of alerting methods contribute to the efficiency and effectiveness of an evacuation. In addition, community familiarity with alerting methods is closely related to evacuation efficiency. Cooperation from evacuees contributes to safe, efficient, and effective evacuations. 1

A well-developed training and exercise program is also a critical element of overall readiness and preparedness for mass evacuations. Training ensures personnel are prepared for their roles. Exercises test the capabilities and resources of the agencies, and when a number of cooperating agencies and jurisdictions are included, they also test and strengthen working relationships. Training and exercises to test and improve plans for an evacuation from a catastrophic incident are especially important because of the large number of agencies and jurisdictions involved in such an evacuation. 2

Several important factors should be considered when making a decision to evacuate an area, but the primary consideration is the potential risk to lives and property. The type of evacuation will be based on the situation. Evacuations are generally classified as one of three types:

Figure 4.4.1.1 Voluntary Evacuation

Figure 4.4.1.2 Recommended Evacuation

Figure 4.4.1.3 Mandatory Evacuation

Disaster related evacuations generally occur in multiple phases which may include readiness/preparation, activation/notification, evacuation/displacement, and re-entry/recovery.

Figure 4.4.2.1 Permanently mounted tsunami evacuation route sign

Figure 4.4.2.2 American Red Cross distributes food to evacuees following a disaster

Traffic management is critical during disaster evacuations to minimize congestion and decrease time. Effective traffic management allows a jurisdiction to evacuate more people from a community in an efficient manner, which reduces the burden on personnel and resources.

Understanding how evacuees may react when confronted with a potential threat or hazard is critical to evacuation planning efforts. Many individuals possess the capability to evacuate from a potentially dangerous area using their own transportation with minimal or no assistance. Others may not have access to transportation or have special needs and require accessible transportation assistance to evacuate the impacted area.

Prior to a jurisdiction issuing an evacuation order, individuals may decide to self-evacuate in reaction to a perceived threat or following an actual incident that has already occurred. These spontaneous evacuees can complicate operations and add confusion to the process. Educating citizens in the identified hazard areas prior to disaster events, clearly defining evacuation routes (Figure 4.4.3-1), and providing timely threat and hazard information are ways to help lessen the impact of spontaneous evacuations.

Figure 4.4.3-1 Example of an evacuation route sign to assist self evacuees

Emergency managers should consider consulting with local tourist destination leaders to discuss the impact of tourist populations on evacuation plans and routes and to identify steps for making evacuation and sheltering decisions. 1

When planning for traffic management, jurisdictions should identify any potential issues related to each specific route (e.g., height or weight restrictions, signal timing, rail crossings) and any resources that may be needed to address these considerations.

Dynamic message signs (Figure 4.4.3-2) and portable signage along evacuation routes can help inform evacuees of respite sites, shelter locations, fuel availability, and medical treatment facilities. Additionally, other traffic incident management strategies and resources such as safety service patrols and towing should be active to maintain the efficiency of evacuation routes.

Figure 4.4.3-2 Dynamic message sign assisting evacuees during a wildfire

Failing to effectively manage traffic during an evacuation increases the burden on resources, extends evacuation times, increases incidents and congestion, and may leave evacuees in vulnerable conditions.

Evacuating impacted individuals prior to or immediately following a disaster can be difficult due to limited transportation infrastructure. Under certain conditions, contraflow lane reversal may provide additional capacity to an existing roadway system to expedite the evacuation process.

Contraflow lane reversal modifies the normal flow of traffic to aid in increasing the flow of outbound vehicle traffic during an evacuation (Figure 4.4.3.1.1). Typically, one or more lanes in the opposing direction of a controlled-access highway are used to increase capacity during the evacuation/displacement phase.

Figure 4.4.3.1.1 Utilizing contraflow to evacuate Houston, Texas ahead of hurricane Rita

Contraflow operations require considerable planning to avoid any interference with response operations since necessary resources will likely be mobilizing into the area while evacuations are taking place. Contraflow may also create issues if the transition from contraflow reversed lanes back to normal lanes is not properly planned. This transition can create bottlenecks and confusion for drivers and significantly slow the evacuation. Contraflow operations also require a significant amount of time and resources to be safely implemented and are therefore most beneficial during large-scale evacuations. Permanently installed traffic control devices and signage will expedite the activation of contraflow plans and free up valuable resources ahead of a disaster (Figure 4.4.3.1.2).

Figure 4.4.3.1.2 Permanently installed signs assist with contraflow during a disaster

Contraflow procedures almost always occur on controlled-access highways. Most contraflow plans operate on divided four-lane controlled-access highways. Traffic in all four lanes is traveling away from the disaster location toward destinations where the dangers posed by the approaching hazard are significantly reduced. Contraflow can also be implemented such that one lane remains in normal operation, carrying disaster response traffic toward the impacted area.

An important consideration in contraflow is the termination point. The inbound traffic is twice the normal flow and must be distributed to minimize congestion. This can be accomplished by locating the terminus at a freeway interchange with direct-connect ramps with a crossover just past the interchange for through traffic. Another method is to use multiple termini directing each lane of contra-flow to a separate exit. Based on infrastructure and traffic needs, the termini should be selected to minimize congestion and driver confusion.

Utilizing shoulders of evacuation routes during a disaster can increase traffic flow out of an evacuation area. Part-time shoulder use is a transportation system management and operation strategy for addressing congestion and reliability issues within the transportation system. There are many forms of part-time shoulder use; however, they all involve use of the or shoulders of an existing roadway for temporary travel during certain hours of the day or the duration of large-scale evacuations (Figure 4.4.3.2).

Figure 4.4.3.2 Freeway shoulders utilized to increase capacity and improve traffic flow

Part-time shoulder use is a form of active traffic management which modifies roadway conditions and controls – in this case the number of lanes – in response to forecast or observed traffic conditions. It may be used in combination with other traffic management strategies, such as overhead lane control signs, dynamic speed limits, and queue warning.

Although part-time shoulder use can be a very cost-effective solution, it may not be an appropriate strategy where minimum geometric clearances, visibility, and pavement requirements cannot be met, or it may have an adverse impact on safety. Part-time shoulder use is primarily used on freeways. Typically, the use is temporary for part of the day or during the evacuation phase of an incident, and the lane continues to operate as a refuge/shoulder when not being used for these travel purposes.

Fuel management is a crucial consideration that jurisdictions must address during the disaster evacuation planning process. Failure to ensure ample fuel supplies are available after an incident will lead to fuel shortages along with associated congestion (Figure 4.4.3.3.1) and impacts to traffic patterns which will negatively affect evacuation operations.

Figure 4.4.3.3.1 Vehicles wait to refuel during following a disaster evacuation order

Supplies of fuel should be maintained to support response and evacuation operations prior to and during an incident, along with the recovery operations immediately following an incident. Partnering with bulk fuel vendors to prioritize deliveries at critical locations will help mitigate the risk of fuel shortages during the initial response.

When planning evacuation routes, consideration should be given to those which have ample businesses to provide fuel to evacuees. Station owners should be encouraged to install generators in the case of power loss, as fuel will be inaccessible without power. An effort should be made to ensure that secondary evacuation routes also have fuel resources available; this may require planning for a temporary respite/fueling site. Working with private sector partners to identify temporary fueling capabilities and supplies is critical in areas where private fueling stations are unavailable.

In areas with an increased number of alternative fuel vehicles, efforts should be made to identify and communicate the locations of alternative fuel sites along the selected evacuation routes (Figure 4.4.3.3.2).

Figure 4.4.3.3.2 Permanent signs indicate alternative fueling locations along evacuation route

The following are transportation, weather, and assessment monitoring and prediction tools that can support an evacuation. 1

Clarus — This is a system that helps predict weather conditions. For those evacuating in advance of a severe storm, weather information plays a key role in their safety. Tropical storms and hurricanes may spawn tornados well in advance of the front and may inundate an area very rapidly. Many victims of storms actually perish due to resultant flooding or secondary tornados. Travelers must be aware of the weather and their environment at all times when evacuating an area. Clarus and other modeling tools available through the National Weather Center are vital to assessing dangers to evacuees while traveling along the evacuation route.

Consequence Assessment Tool Set/Joint Assessment of Catastrophic Events (CATS/JACE) — This model was developed under the guidance of FEMA and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency. The CATS/JACE software provides disaster analysis in real time with an array of information integrated from a variety of sources. The software is deployable for actual emergencies with capabilities including contingency and logistical planning as well as consequence management. The CATS program integrates hazard prediction, consequence assessment, and emergency management tools with critical population and infrastructure data. It uses tools and data that predict the hazard areas caused by manmade events and natural disasters including earthquakes and hurricanes. CATS assists with estimating collateral damage to facilities, resources, and infrastructure, and creates mitigation strategies for responders.

Dynamic Network Assignment-Simulation Model for Advanced Road Telematics (Planning version)—DYNASMART-P — FHWA supported the development of this model by the University of Maryland to support network planning and traffic operations decisions through the use of simulation-based dynamic traffic assignment. FHWA is examining the application of this model for emergency transportation management analysis.

Evacuation Traffic Information System (ETIS) — FHWA currently supports the ETIS, which is a web-based program that facilitates the sharing of evacuation and traffic information among coastal states in the Gulf Coast and southeast from Texas to Virginia. The ETIS supports decisions such as evacuation type (e.g., voluntary, mandatory, staged) and implementation of contraflow or lane-reversal operations. The ETIS was originally developed under the auspices of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, but is now under FHWA sponsorship, and operated by its private developers.

Evacuation Travel Demand Forecasting System — This is a macro-level evacuation modeling and analysis system that was developed in the aftermath of Hurricane Floyd to address the need to forecast and anticipate large, cross-state traffic volumes. This is a web-based travel demand forecast system that anticipates evacuation traffic congestion and cross-state travel flows for North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The Evacuation Travel Demand Forecasting System model was designed so emergency management officials can access the model online and input hurricane category, expected evacuation participation rate, tourist occupancy, and destination percentages for impacted counties. The output of the model includes the expected level of congestion on major highways and tables of vehicle volumes expected to cross state lines by direction.

Hazard U.S.—Multi-hazard (HAZUS-MH MR2) — Developed by FEMA, this model is a loss estimation and risk assessment program covering earthquakes, hurricanes, and flooding. By modeling the physical world of buildings and structures and then subjecting it to the complex consequences of a hazard event, users can implement this tool to prepare for a natural disaster, respond to the threat, and analyze the potential loss of life, injuries, and property damage.

Hurricane and Evacuation (HURREVAC) — This is a program that uses GIS data to correlate demographic data with shelter locations and their proximity to evacuation routes to estimate the effect of strategic-level evacuation decisions.

MASS eVACuation (MASSVAC) — This is a macro-level model originally developed for the purpose of modeling nuclear power plant evacuations. More recently, it was applied to test operational strategies for hurricane evacuations in Virginia.

Network Emergency Evacuation (NETVAC) — NETVAC was developed as part of the reaction to the Three-Mile Island nuclear reactor incident in 1979. While strong in terms of a response to a Point A-to-Point B situation, it is limited in application to hurricane evacuation, which often includes multiple Points A and B. However, transportation and emergency managers may seek to use this model to analyze route selection, intersection controls, and lane management.