Mitigation activities prevent or reduce future emergencies caused by disastrous events and minimize their effects on road function.

Mitigation refers to the activities that prevent emergencies caused by a disastrous event, reduces the likelihood of emergencies occurring, or relieves the impact of unavoidable emergencies on roads. Mitigation is a broad-based, long-term, strategic approach to all potential disasters managed mainly by national and local governments or related agencies. Mitigation activities may be carried out before, during, or after a disaster, but generally refers to pre-disaster activities.

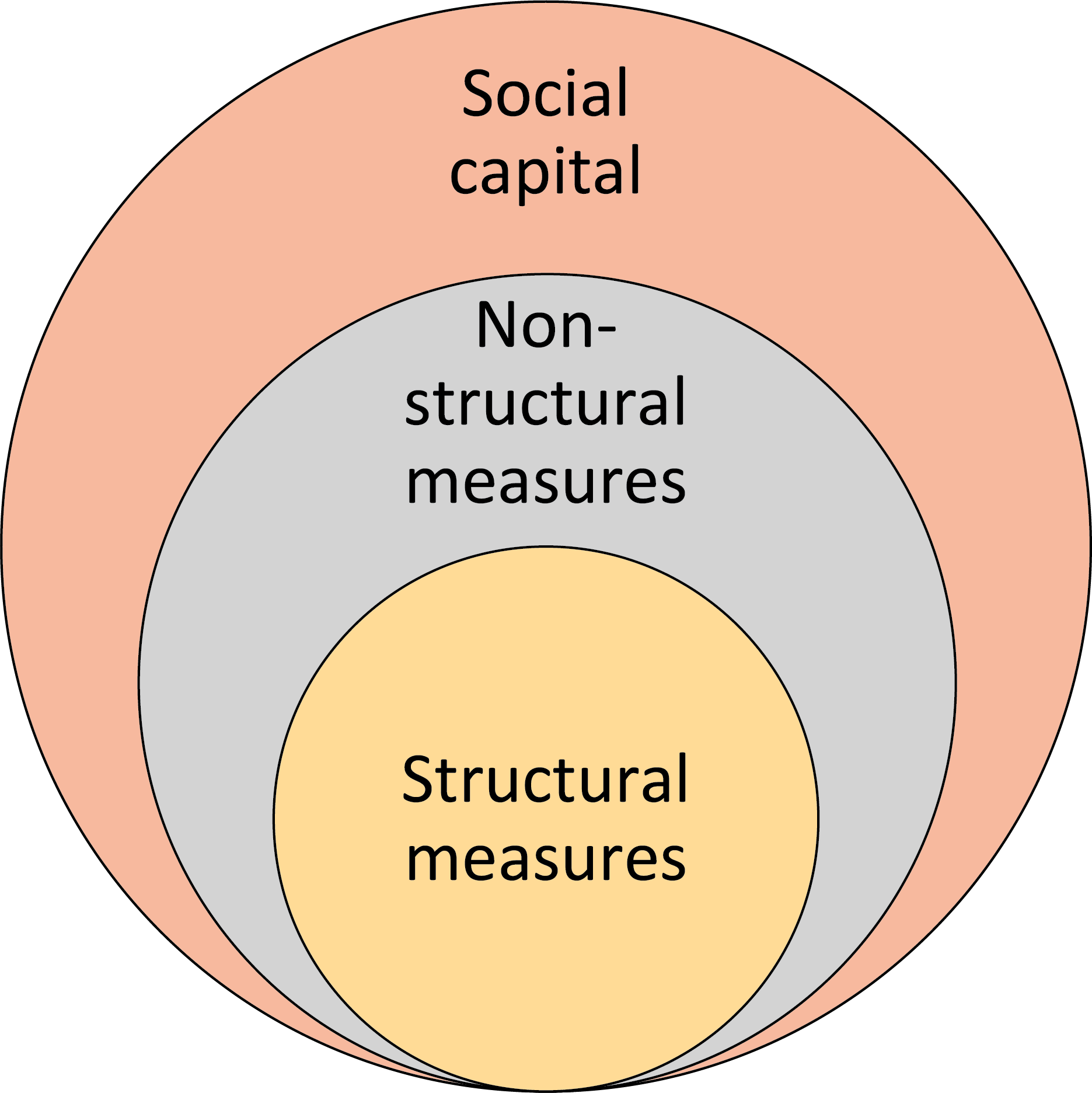

Mitigation is a combination of structural and non-structural measures. Structural measures are any physical construction to reduce or avoid possible impacts of hazards or the application of engineering techniques or technology to achieve hazard resistance and resilience in structures or systems. Non-structural measures are measures not involving physical construction that use knowledge, practice, or agreement to reduce disaster risks and impacts, in particular through policies and laws, raising public awareness, training, and education 1. Measures such as disaster insurance are also part of the non-structural measures. Mitigation approaches by both structural and non-structural measures is key for sustainable development and elimination or reduction of future risks. Mitigation is planned on a long-term basis because it is important to develop road users' expectations and demands for road resilience. It also helps users understand at what level and in what prioritized order national and local governments or related agencies can meet and maintain those expectations and demand with limited resources. It is important to identify and organize resources, assess risks appropriately, identify mitigation measures to reduce the impacts of hazards, and prioritize implementation plans.

In recent years, community disaster management has focused on strengthening social infrastructure, called social capital or community resilience, which refers to the ability of a community or neighborhood to work together to cope with disasters and resume daily life 2. With regard to roads, this is still in the early stages of discussion and is expected to be explored in the future.

Mitigation requires the development of long-term visionary measures with road users and other stakeholders for both structural and non-structural measures.

Mitigation measures must be taken to protect the lives and economic activities of citizens against serious effects in the event of a disaster. It is important to consider "worst-case scenarios" for "severe" and "frequent" disasters in order to avoid "unforeseen" situations. However, it is not realistic to protect against such external forces only by means of structural measures, both in terms of finances and the social and natural environment. The basic principle of disaster mitigation against "relatively high-frequency events" is the use of structural measures, but we must also consider the use of non-structural measures to mitigate against the events that exceed the frequency 1.

In recent years, it has been recognized that comprehensive disaster prevention and disaster mitigation measures are important to strengthen the disaster prevention capacity of local communities with a balance between self-help, mutual aid, and public assistance, including local residents and enterprises 2. Particularly as regards flood and tsunami countermeasures, activities to promote understanding of disasters, share awareness of vulnerability and improve response to emergencies have been intensified. In roads sector, regional cooperation against tsunami disasters is under development regarding evacuation. The study of coping capacity of local residents for road disaster prevention has just begun.

Figure 2.1 Components of Disaster Mitigation

UN office for disaster risk reduction defines that structural measures are any physical construction to reduce or avoid possible impacts of hazards, or the application of engineering techniques or technology to achieve hazard resistance and resilience in structures or systems 1.

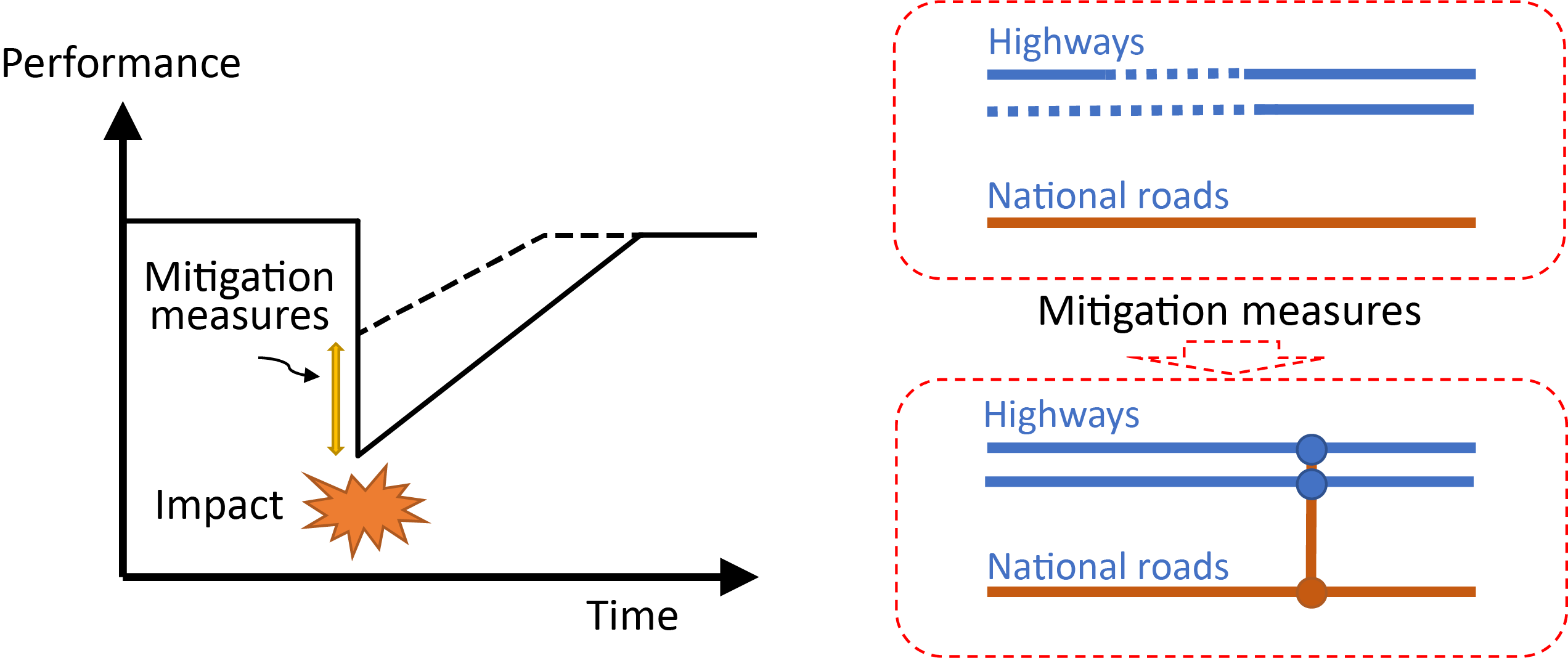

Structural mitigation measures for roads also consist of measures for structure and measures for systems.

Linkov discuss infrastructure resilience in terms of the resilience of individual infrastructures and the resilience of networks. Not only does it mean that individual infrastructures are low impact and able to recover quickly from a disaster event, but it also recommends efficient and redundant networks in terms of disaster resilience of the supply chain. Infrastructure and network resilience are also important components of structural mitigation measures 2.

As described above, it is important to ensure the disaster-resistant performance of tunnels, bridges, and embankments on longitudinal roads, transverse roads, and urban roads in a unified manner to cope with severe and widespread disasters, so that the roads can function quickly at the time of a disaster. In addition, it is important that multiple road networks ensure uninterrupted human and logistical flow to the disaster area, minimizing the loss of life and economic losses. Figure 2.2-1 shows the schematic image of the measures for structure and measures for systems.

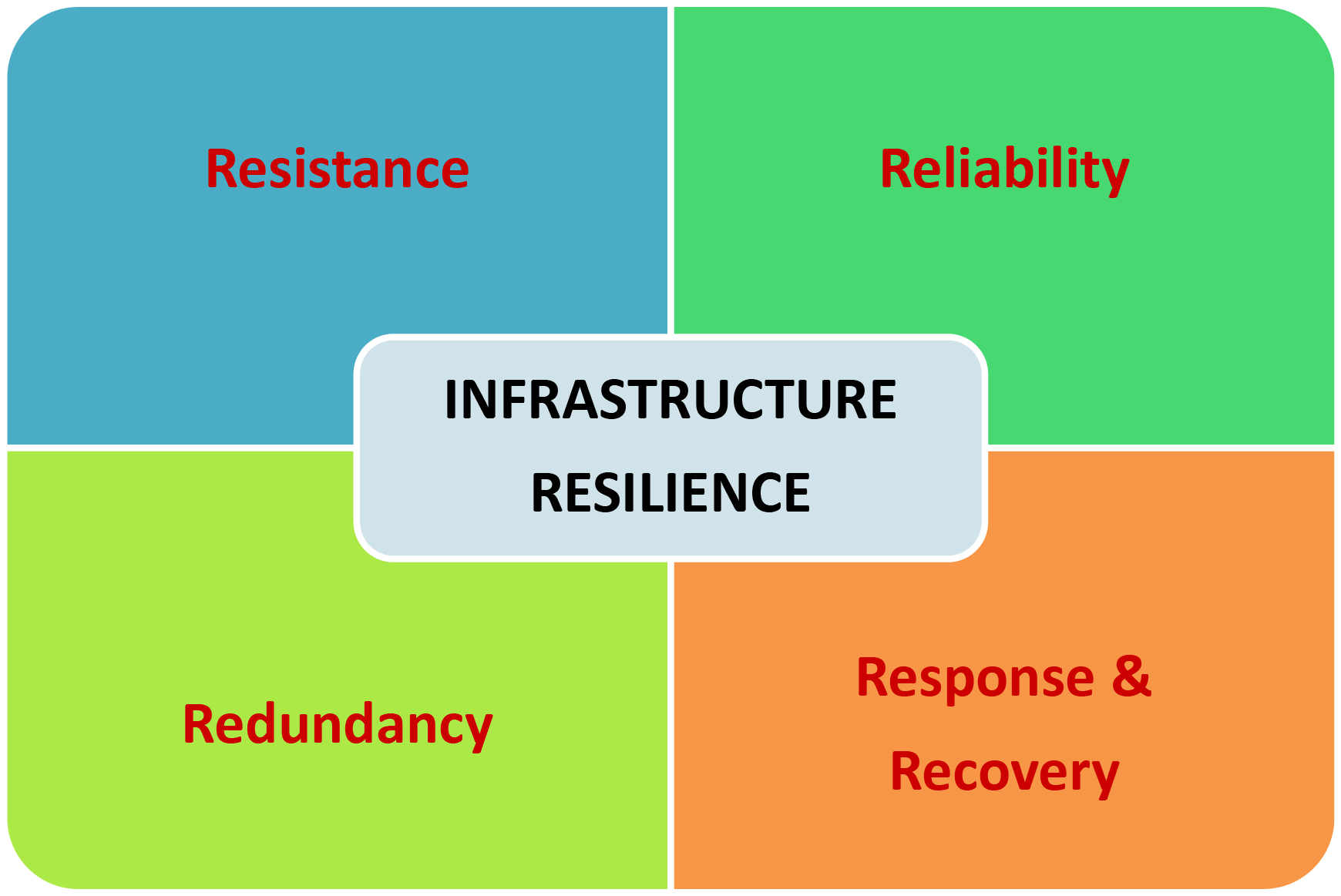

The UK Critical Infrastructure Resilience Improvement Guide defines resilience as the ability of assets, networks, and systems to prevent and mitigate disruptive events, adapt to disruptive events and recover quickly from disruptive events. This also indicates that the four components of resilience components “resistance", "reliability", "redundancy" and ”response & recovery” as shown in Figure 2.2-2 are necessary in order to build infrastructure resilience. Ensuring "resistance", "reliability" and "redundancy" are also the key components of structural mitigation measures3.

Figure 2.2-1 The components of structural measures for infrastructure resilience

Figure 2.2-2 The components of infrastructure resilience

It is important to make sure that tunnels, bridges, embankments, and other structures in nationwide roads and urban roads have the same disaster-resistance performance to cope with increasingly severe and widespread disasters so the roads can perform their function even in the event of a disaster.

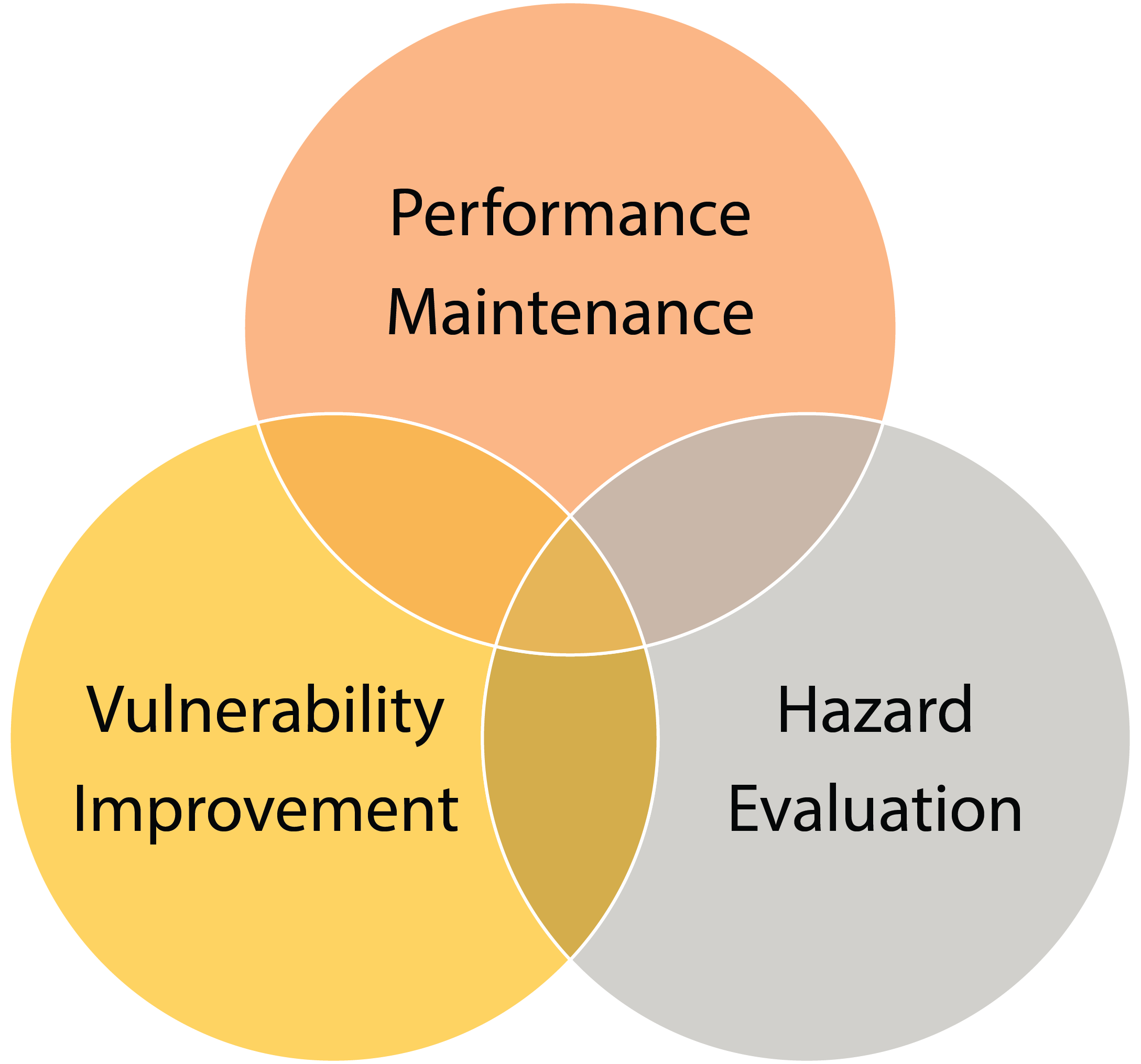

Improving the disaster resilience of road infrastructure consists of 1) estimation of external disaster forces based on the latest knowledge, 2) improvement of infrastructure performance based on the estimated external disaster forces, and 3) maintenance of infrastructure and keep its performance by appropriate repairs and upgrades. Road infrastructure used to be built based on external disaster forces estimated from the historical record and historical events at the time of design and the design standards based on the technical knowledge at the time of design, and much of the maintenance is focused on maintaining serviceability. It is important to increase the resilience of infrastructure through priorities based on smart investment strategies based on the latest hazard analyses, hazard assessments based on the latest knowledge and structural vulnerability assessments of the infrastructure. In addition, infrastructure must be properly maintained and managed, and consideration must be given to ensuring that not only its serviceability but also its disaster resistance does not deteriorate over time.

Innovative materials and designs can enhance the resilience of road infrastructure.

Figure 2.2.1.1 Key component of resilient road infrastructure

Road infrastructures have been subjected to more severe and widespread natural disasters in recent years. In this context, the evaluation of hazards to the road infrastructure has steadily progressed as scientific advances have revealed the causes and mechanisms of natural hazards such as earthquakes and other disasters. Proper assessment of disaster forces is the first step in ensuring that roadway functions, whether new or existing infrastructure, remain its function during and after the disaster. With regard to the estimation of disaster forces, it is necessary to assess the hazard, assess the criticality and vulnerability of the road infrastructure, and rank them in terms of smart investment strategies.

With regard to seismic hazards, it is important to assess the hazard of the road infrastructure considering the seismic environment, i.e., the identified faults, the location of the identified infrastructure, and the identified infrastructure structure. It is important that hazard assessments always reflect the latest knowledge.

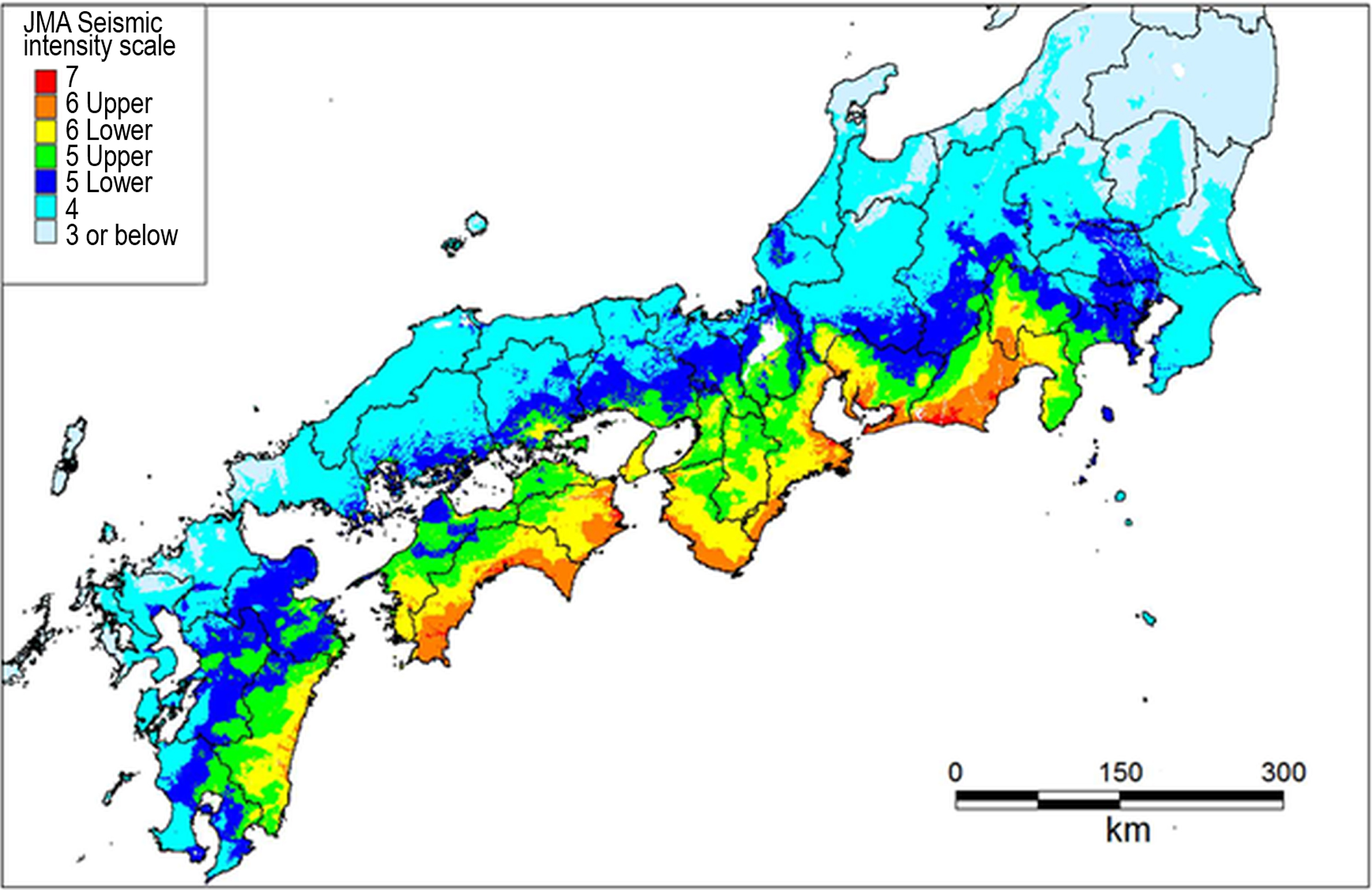

Figure 2.2.1.2 Example of hazard identification and evaluation

(A case of simulation result of Far-field earthquake in Japan) 1

Road infrastructures have suffered collapses and failures due to various disasters. Based on these lessons learned, the mechanisms of damage have been elucidated and the design methods have evolved accordingly in order to ensure the safety of human life and structures of road infrastructures. In recent years, disasters have tended to be much larger and more widespread than expected. There is no better way to ensure that the road infrastructure does not suffer damage, but at the very least, it is necessary to improve it so that society will not lose its functions even if it is damaged.

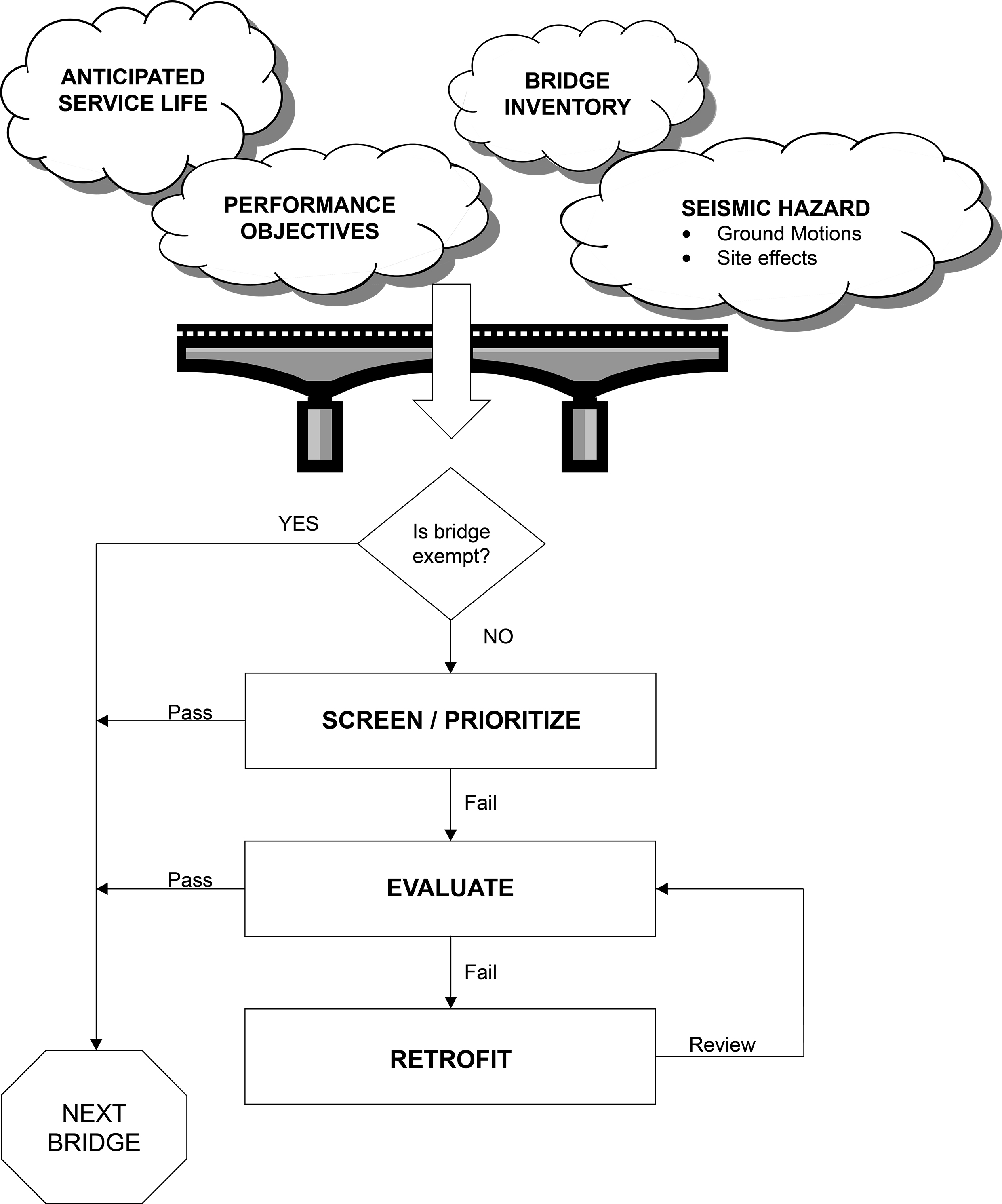

Road infrastructure needs to maintain essential road functions even if it is damaged, in order to respond to emergency situations during a disaster, as well as for rapid recovery after a disaster. Therefore, the design of road infrastructure has come to consider the safety of human life, such as the preservation of human life, the safety of the structure so that it does not collapse, and the functionality of the structure so that it can be easily restored to its original function as a bridge 2. It is important to clearly identify and design the level of various road functions such as safety, repairability, usability, serviceability, safety and durability against external disaster forces. Figure 2.2.1.3 shows an example of the retrofitting process for highway bridges 3.

Figure 2.2.1.3 Example of the retrofitting process for highway bridges

Hazard assessment and appropriate design for the estimated hazards are the basis of structural mitigation measures for road infrastructure. However, after building the infrastructure, good maintenance and proper repair of the road infrastructure are key to maintaining the resilience performance considered in the design. Day-to-day maintenance is often focused on serviceability and usability. However, the ability to maintain the road functioning in a disaster by daily maintenance will make the difference between a good road manager and not.

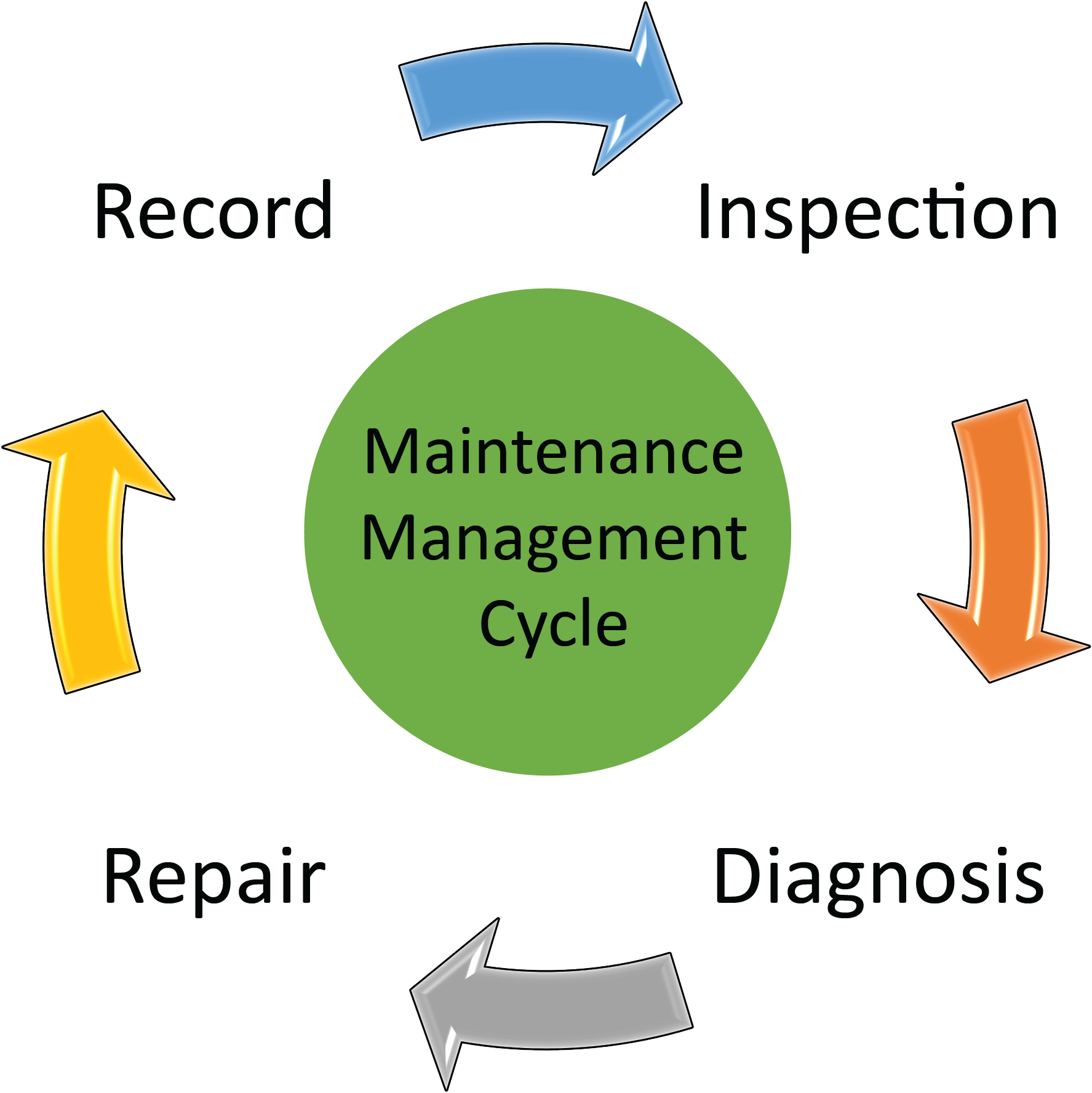

It is important to implement a maintenance cycle of inspection, diagnosis, repair and documentation (Figure 2.2.1.4) to ensure that the infrastructure is continuously in good service and resilient to extreme natural hazard events. Such a well-rounded maintenance environment is also a cornerstone of being able to continue operations and provide a foundation for timely restoration in the event of a disaster. In road management, the maintenance manager is a key leader in the restoration effort and therefore needs to be equipped with not only knowledge of the facility and its operation, but also the ability to solve problems in an emergency.

Figure 2.2.1.4 Maintenance Management Cycle

The disruption of the road network will affect a rescue, evacuation, and firefighting activities immediately after a disaster. If the road recovery is delayed, the transportation of goods and materials, and economic activities may be severely affected for a long time. It is an important issue for road managers to maintain the road function during and after a disaster. Having a redundant road network provides that even if a part of the route is disrupted, there will be alternative routes, and the overall road function will be maintained. Thus, it is important to increase the resilience of the road as a whole, not only from the resilience of the road infrastructure as a line but also from the resilience of the road infrastructure as a plane.

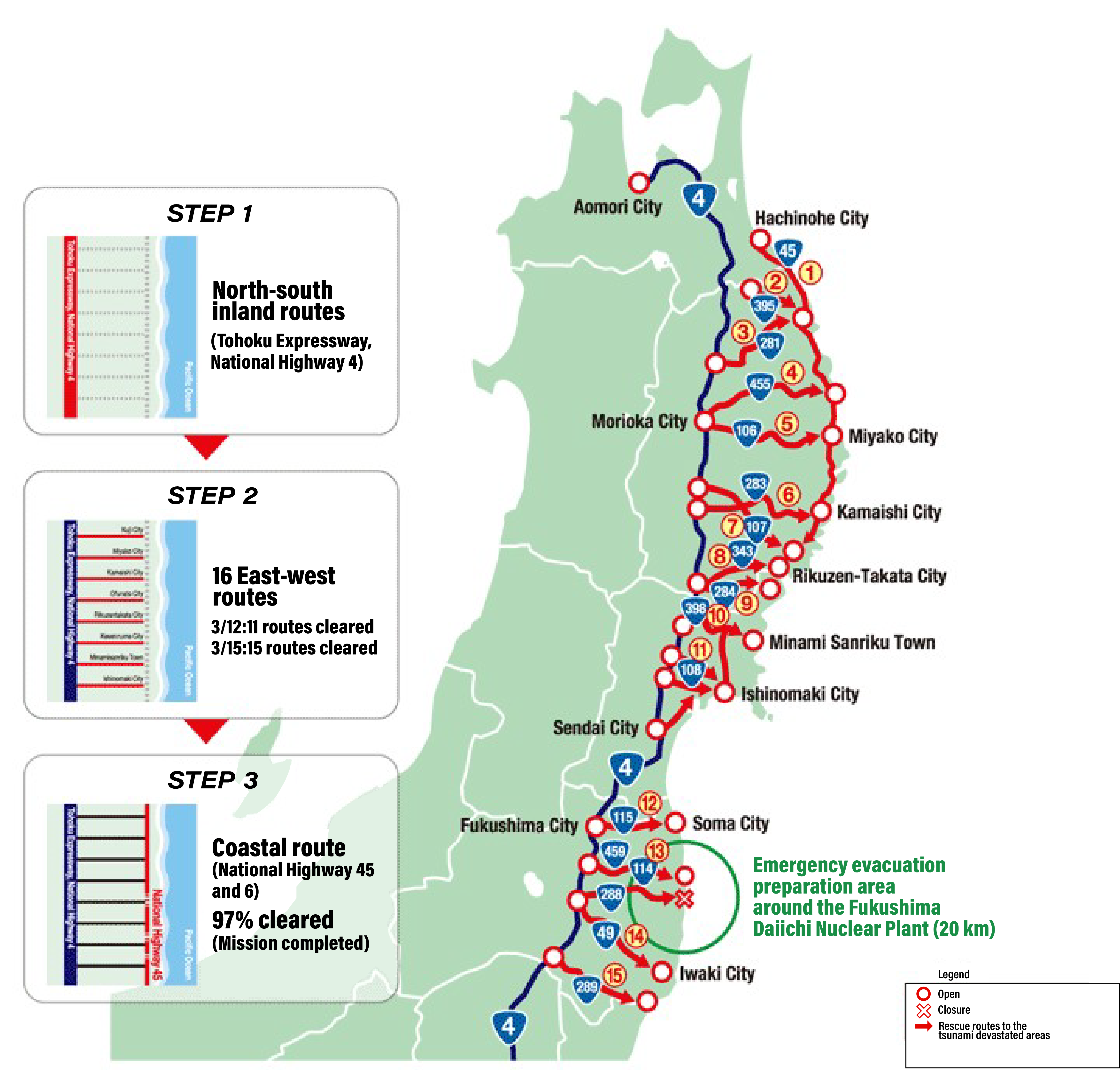

However, the development of a redundant road network is controversial in terms of cost-effectiveness and efficiency of daily economic activities. Therefore, it is important to properly evaluate in the road development plan both in terms of disruption of various road functions such as handling of detour traffic in case of disruptions, securing evacuation routes, medical and emergency activities, and the effectiveness of avoiding such disruptions by a network with a certain level of redundancy. Figure 2.2.2 shows the map of the operation “teeth of a comb” that was taken for clearing of the road that are located in poor road network at the 2011 East Japan earthquake.

Figure 2.2.2 Operation "Teeth of a Comb"

* Operation “Teeth of a Comb” 1 was carried out to secure the human life of tsunami-affected area where redundant road networks were not well developed. (2011 East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami).

1 https://www.preventionweb.net/terminology/view/505

2 2014, Daniel ALDRICH, Social capital and disaster, ESTRELA No. 246, September [In Japanese translated by Yuu ISHIDA and Yoshikazu FUJISAWA]

1 2017, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Towards New Stage of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Measures, [In Japanese]

2 2017, Katsumi YUKAWA et al, New Trend in Disaster Management, The report of Japan Institute of Country-ology and Engineering, Volume 30, January [In Japanese]

1 2019, Cabinet office of Japan, Hazard estimation caused by Nankai-trough great earthquake (Damage to infrastructures), July (In Japanese), http://www.bousai.go.jp/jishin/nankai/taisaku_wg/pdf/1_sanko.pdf

2 2012, National Institute for Land Infrastructure Management (NILIM) and Public Works Research Institute (PWRI), Technical Notes’s on Seismic Retrofit Design of Bridges, Technical Note of NILIM No.700 and Technical Note for PWRI No.4244, November

3 2006, Federal highway administration, US department of transportation, Seismic retrofitting manual for highway bridges, January

1 http://infra-archive311.jp/en/gaiyou02.html

The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction defines that “Non-structural measures are measures not involving physical construction which use knowledge, practice or agreement to reduce disaster risks and impacts, in particular through policies and laws, public awareness raising, training and education.”

Disaster mitigation measures for roads include "structural measures," such as road slope disaster prevention and mitigation for road slope, for road bridge retrofit, bridge scouring and so on; "non-structural measures," such as building cooperation and coordination systems, raising awareness of disaster prevention, citizen participation for disaster prevention, and stable financial support for disaster; and "social capital," which supports these measures. "Social capital" is discussed later.

In general, it takes a long time to construct structural measures, and they cannot be fully effective against disasters that exceed the target disaster scale. Therefore, it is important to minimize the impact of disasters by implementing feasible non-structural measures before and after the completion of structural measures, and by implementing non-structural measures that can be combined with appropriate structural measures to create complementary and synergistic effects.

Structural measures are mostly the measures that are positioned as "mitigation" in the disaster management cycle. Non-structural measures can be found in a wide range of areas in the disaster management cycle, including mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery.

Non-structural measures in the "mitigation" category include "building a cooperative and coordinated system," "raising awareness of disaster preparedness," "citizen participation" and "stable financial support". The non-structural measures in the "mitigation" category are more long-term than the non-structural measures in the "preparation" category.

In the event of a large-scale disaster, not only the workload will increase due to the occurrence of the disaster, but also the road management capacity itself will decrease due to the disruption of lifelines, the disconnection of information and communication networks, the damage to road management facilities, and unfortunes to the employees who manage the roads. Therefore, there is a very high possibility that the disaster response of road managers will be limited and they will not be able to carry out a huge amount of emergency response activities promptly.

In such a situation, it would be effective to conclude in advance an "emergency cooperation agreement" between road managers and private contractors, consultant companies, and related companies covering support for various emergency response activities such as the implementation of emergency operations, emergency supply and transportation of goods, etc.

Furthermore, mutual-cooperation agreements between road administrators and local governments have also been observed, and in many cases, agreements are concluded not only for emergencies but also for cooperation during normal times.

This trend was particularly evident in Japan after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995, which many lessons on rapid emergency recovery measures.

Figure 2.3.1 Disaster Agreement (Emergency cooperation agreement)

Wait for the report of this 2020-2023 cycle.

1, 2, 3, 5 2013, Y. Tannnaka, Disaster agreements and cooperation with private organizations, Journal of road engineering and management review, vol. 872, November (In Japanese)

4 2016, PIARC TC 1.5 “Risk Management”, Risk management for emergency situations, 2016R26EN

6, 7 (For example) 2012, Chiba prefecture, NEXCO East, and Metropolitan Expressway: "Comprehensive partnership among Chiba prefecture, NEXCO East, and Metropolitan Expressway”, October, https://www.shutoko.co.jp/company/press/h24/data/10/1009/ (In Japanese)

8 (For example) 2011, Hanshin Expressway and 6 other urban expressway companies and public corporation: "Agreement on mutual cooperation in emergency restoration work such as during the earthquake", March, (In Japanese), http://www.hanshin-exp.co.jp/topics2/1330999646F.pdf (In Japanese)

9 (For example) 2009, Hanshin Expressway and Kansai Branch of Japan Federation of Construction Contractors: "Agreement on emergency measure activity in the event of a disaster", April(In Japanese)

10 Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, Why road "clearing" is done quickly, http://www.thr.mlit.go.jp/road/jisinkannrenjouhou_110311/keikairiyuu.pdf (In Japanese)

11 (For example) 2009, Hanshin Expressway and Kansai Branch of Japan civil engineering consultants association: "Agreement on emergency measure activity in the event of a disaster", April (In Japanese)

12 2011, Kinki Branch of Japan civil engineering consultants association: “Large-scale disaster at Kii peninsula, No.12 Typhoon (In Japanese)

13 Road Division, Panel on Infrastructure Development, MLIT: “For ensuring the reliability of the country, including disaster prevention”, Nov. 2012, http://www.mlit.go.jp/common/000229314.pdf (In Japanese)

14 2019, PIARC TC E.3 ”Disaster management”, Disaster information management for road administrators, 2019R09EN

1 2017, Queensland Government, Queensland Government Crisis Communication Plan, December

1 2017, S. Takeshita et al, Guidelines for Applying the Tendering and Contracting Method in Disaster Recovery, Journal of JACIC information, No. 116, July (In Japanese)

2 2017, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and tourism of Japan, Guidelines for Applying the Tendering and Contracting Method in Disaster Recovery, July (In Japanese)

3 2021, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and tourism of Japan, Guidelines for Applying the Tendering and Contracting Method in Disaster Recovery (Revised on July 2021), July (In Japanese)

4 2017, S. Takeshita et al, Guidelines for Applying the Tendering and Contracting Method in Disaster Recovery, Journal of JACIC information, No. 116, July (In Japanese)

5 2021, H. Yoshida, Toward quick disaster restoration” -Development of Guidelines for Applying the Tendering and Contracting Method in Disaster Recovery, Construction monthly, Vol. 65, Japan construction engineers’ association, July (In Japanese)

Structural and non-structural measures are the powerful measures for disaster mitigation. However, the either of the two measures will not be effective if they would be implemented independently. To enhance the functions provided by both measures, it is important to integrate both measures so that they can function together. But there is another aspect to be considered.

There is some limitation of hazards that can be mitigated by structural measures so that non-structural measures should be taken to cover them. Therefore, it is necessary for residents in the possible disaster area to be aware of disaster risks and to accurately recognize the limitations of structural and non-structural measures. In other words, for disaster mitigation measures to be effective, it is important not only for government-led structural and non-structural measures, but also for local people to be aware of disaster mitigation, to have a common understanding of disaster risks, to share knowledge and roles regarding disaster mitigation measures, and take actions together.

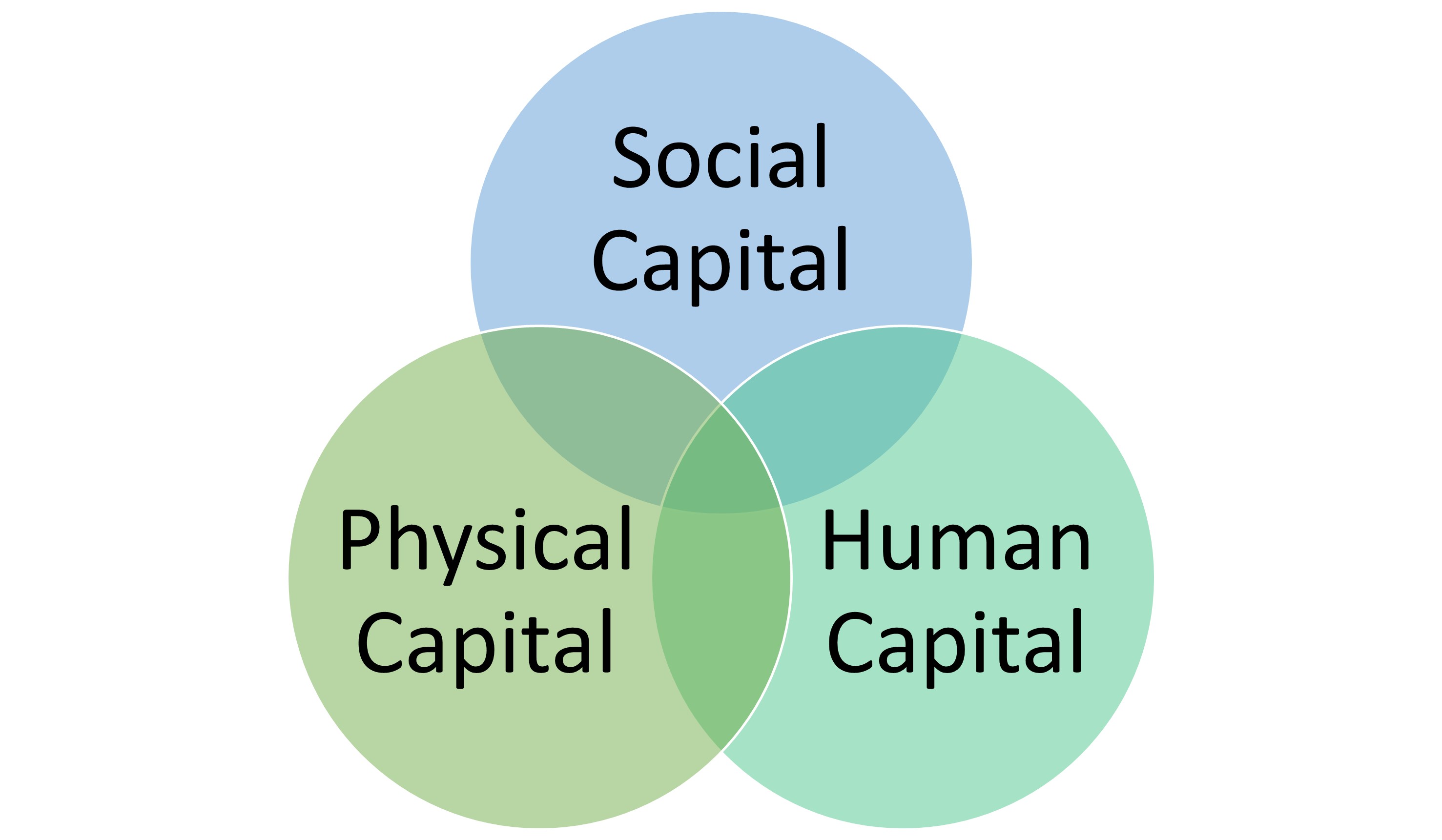

In the field of sociology, there is a concept called social capital. Social capital is a new concept along with Physical Capital and Human Capital 1. According to Wikipedia, social capital is defined as "effective functioning of social groups through interpersonal relationships, a shared sense of identity, a shared understanding, shared norms, shared values, trust, cooperation, and reciprocity 2. Social capital is a measure of the value of resources, both tangible (e.g., public spaces, private property) and intangible (e.g., actors, human capital, people), and the impact that these relationships have on the resources involved in each relationship, and on larger groups." Figure 2.4-1 shows the concept of the three major capitals.

Figure 2.4-1. Three Major Capitals

It is said that there is a positive correlation between social capital and civic activities, and it is pointed out that if social capital is rich, participation in civic activities is promoted, and furthermore, social capital is cultivated through the activation of civic activities 3. It is now widely recognized that "self-help, mutual-help, and public-help" are important to enhance community disaster preparedness. Social capital is considered to be a major foundation for the resolution of local issues and revitalization. In other words, social capital is expected to play an important role in disaster mitigation as a regional issue.

Research on social capital in the field of disaster mitigation started around 2008. It has been reported that discussions on disaster prevention in local communities have led to the formation of networks among community members and the development of a sense of mutuality (norms and reciprocity) and trust. There can be found some cases where disaster prevention has activated the "social capital" of local communities 4. In other words, there are cases where disaster reduction has activated the "social capital" of the local community. This shows that the revitalization of local communities and local disaster reduction capacity are inextricably linked. It is desirable that local efforts to promote disaster reduction will activate local community vitalization, which in turn will improve local disaster reduction capacity and road disaster reduction. As a result, it is expected to pave the way for more detailed urban planning in accordance with the actual conditions of each district.

Figure 2.4-2. Evacuation Drill with Local Residents 2015, West Nippon Expressway Company Limited. Communication report of NEXCO West group 2015

In the area of road disaster management, a steady but budding effort to improve disaster preparedness through dialogue with local communities and raising public awareness has begun. These include: the use of road slopes as tsunami shelters in cooperation with local communities; the participation of citizens in the design of road restoration projects; budding efforts to promote road maintenance and management while raising public awareness; collaborative efforts in school education; and efforts to pass on disaster experience. Figure 2.4-2 5. shows the evacuation drill between highway authorities and local residents. These efforts are still in the process of trial and error, but they are showing steady results.

The synergistic effect of social capital in the field of road disaster management has only just begun. Further development is expected in the future.

Recent studies on disaster management have shown that the perspective of disaster management needs to shift its focus from "response and recovery" to sustainable disaster mitigation. In order to achieve this shift, it is suggested that disaster management and community planning need to be integrated. Successful disaster "mitigation" also requires the inclusion of public participation at the local decision-making level in the disaster management process 1. This approach of involving citizens in disaster management before, during and after a disaster is known as "public engagement".

Public engagement in road disaster management is still in the research stage, but some initiatives have been initiated.

Social capital can be an important factor in disaster preparedness. Increased awareness of disaster preparedness and prevention among local residents will increase social capital, and increased social capital will increase local disaster preparedness.

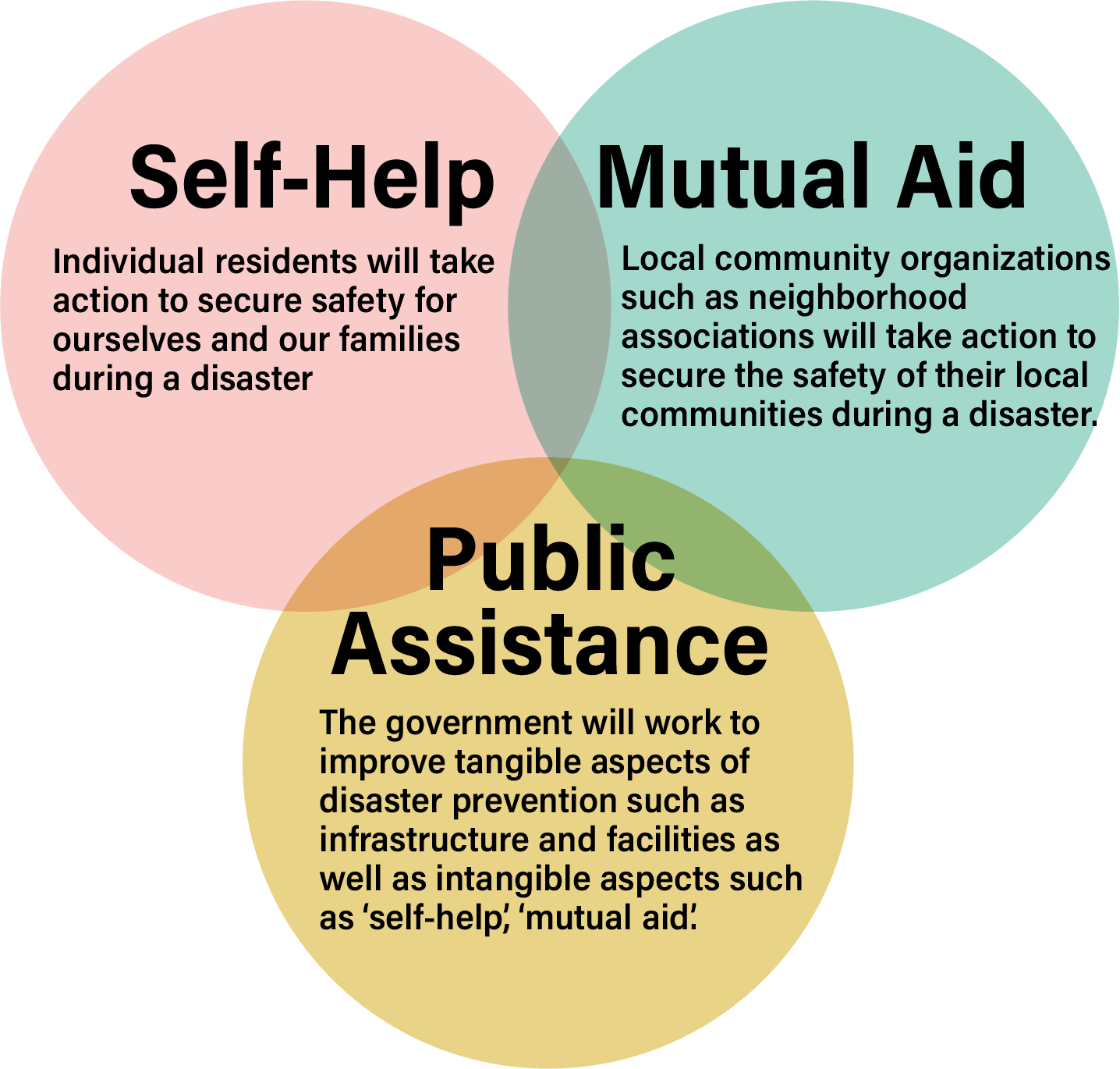

In order to protect life, body, and property from disasters, it is of utmost importance to build a disaster-resistant community, and there are limits to the extent to which the government can respond to disasters. It is essential for citizens and the government to cooperate with each other in disaster management based on the principles of "Self-Help" to protect oneself, "Mutual-Aid" to support each other in one's neighborhood, and "Public-Assistance" for the government to support citizens. Figure 2.4.1 shows the basic relations among Self-help, Mutual-aid, and public-assistance. In order to achieve this, it is important for citizens themselves to further raise their awareness of disaster prevention, to pass on the lessons and knowledge gained from the experience of the earthquake to future generations, and to maintain and develop the bonds of support they have received from each other in their local communities and from organizations and people in Japan and abroad 2. In this way, the "power of citizens" is important in disaster management, and this is also the "role of citizens".

Figure 2.4.1 Self-help, Mutual-aid, and public-assistance

This role of local residents in disaster preparedness is clearly stated in Japan's Basic Act on Disaster Management as the "responsibility of residents" in disaster management. 3

(Basic Principles)

Article 2

(ii) (Omitted) disaster management activities conducted voluntarily by each resident and those conducted voluntarily by voluntary disaster management organizations (which means voluntary disaster management organizations based on a spirit of mutual cooperation among residents; the same applies hereinafter) and other various actors in the area are promoted as well;

(Responsibilities of Residents)

Article 7

(3) (Omitted) based on the Basic Principles, local residents must endeavor to take measures to store goods of daily necessity such as food and drink and to prepare for disaster by themselves and contribute to disaster management by voluntarily participating in disaster reduction drills and any other disaster management activities and handing down lessons learned from past disasters, and any other challenges.

The following explanations have been added to the above laws 5.

From the above, it can be seen that the "responsibility of citizens" in disaster management is to "prepare for disasters on their own" and "voluntarily participating in disaster prevention activities." In order to mitigate the damage caused by major disasters that are likely to occur in the near future, it is essential for citizens and communities to be aware of the importance of taking proactive and positive actions during normal times, in addition to measures taken by the government. For this reason, it is important to provide more opportunities for citizens to think about disaster prevention and to consider a mechanism for citizens to participate in disaster prevention planning and activities.

Road administrators have also started the following budding activities to encourage citizens as road users or as members of local communities near roads to "prepare for disasters on their own" and "voluntarily participate in disaster prevention activities".

Coping capacity is the ability of people, organizations and systems, using available skills and resources, to manage adverse conditions, risk or disasters. The capacity to cope requires continuing awareness, resources and good management, both in normal times as well as during disasters or adverse conditions. Coping capacities contribute to the reduction of disaster risks.

Strengthening disaster preparedness through self-help and mutual-aid is considered to be essential for coping capacity with large-scale wide-area disasters. It is said that when a local community has 1) a human network, 2) a sense of mutuality (norms and reciprocity), and 3) mutual trust, mutual aid activities are more likely to flourish and have a positive impact on disaster management activities. Social capital is considered to be that which enhances social efficiency by focusing on these factors. It is also said that "social capital" in local communities is activated by disaster preparedness, and there is a relationship between "social capital" and "local disaster preparedness" that enhances both. Civic engagement" is one of the civic activities to enhance social capital. Citizens' individual and collective involvement in public issues is an important factor in building social capital.

In the field of tsunami countermeasures for roads, there are examples of cooperation between highways and local communities to strengthen the disaster prevention capability of local communities in terms of tsunami evacuation. In the area of maintenance management, citizens have begun to participate in the process of inspecting and reporting damage to local roads. These are just a few examples of budding citizen participation activities that contribute to road disaster prevention and regional disaster prevention.

It remains to be seen how the disaster preparedness of local communities can enhance the disaster preparedness of expressways, but at the very least, road administrators need to work together with local communities on disaster prevention.

The purpose of disaster prevention education is to learn how to protect lives in the event of a disaster. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to know the mechanism of disaster occurrence, to know the actual disaster prevention capacity of the society and the community, to learn how to prepare for disasters, to learn how to cope with disasters, and to put what they have learned into practice 1. At the same time, it is also important for disaster prevention education to accurately pass on the severity of the disaster, its impact on society, the experience of the disaster, and the wisdom of the people so that the same experience will never be repeated 2. Organizations related to highways often engage in disaster prevention education mainly for the latter purpose.

The following are some of the ways in which road-related organizations provide disaster prevention education

(1) Cooperating with general education programs at elementary schools and specialized education programs at universities as a proactive approach.

(2) Exhibiting educational materials such as damaged structures and posting video materials on the web.

Figure 2.4.3 shows the monumental stone of the tsunami that shows the lessons from the disaster. 3

Figure 2.4.3 Monumental Stone of Tsunami

1 2001, Putnam, Robert D. 2001. “Social Capital: Measurement and Consequences.” Isuma: Canadian Journal of Policy Research 2, Spring

2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_capital

3 https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r98520000011w0l-att/2r98520000011w95.pdf

4 Ministry of land, infrastructure, transportation, and tourism, White paper „Disaster prevention” |Special Feature: Chapter 5.4 Future Direction: Social Capital and Revitalization of Local Disaster

5 Management Capacity (In Japanese) http://www.bousai.go.jp/kaigirep/hakusho/h26/honbun/0b_5s_04_00.html

6 2015, West Nippon Exprwessway Company Limited. Communication report of NEXCO West group 2015

1 2003, Pearce, L. Disaster Management and Community Planning, and Public Participation: How to Achieve Sustainable Hazard Mitigation. Natural Hazards 28, 211–228.

2 2014, 2014, Ishinomaki City, Ishinomaki City Basic Ordinance for Disaster Prevention

3 https://sendai-resilience.jp/en/efforts/government/development/

4 http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?id=3322&vm=&re=

5 2016, Gyousei, Article Explanation, Basic Act on Disaster Management

1 http://www.bousai.go.jp/kohou/kouhoubousai/h21/01/special_01.html

2 http://www.bousai.go.jp/kyoiku/kyokun/kyoukunnokeishou/

3 https://www.city.miyako.iwate.jp/kikaku/teiju/miyakotte.html

1 2019, T. Seto et al., The development of open source based citizen collaboration applications for infrastructure management: My City Report, Proceedings of the29th International Cartographic Conference, July, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6a17/b0f3485d129ee90c6715b1944e5a23205ea1.pdf

3 https://sf311.org/information/recent-requests

5 http://udottraffic.utah.gov/CitizenReporting.aspx

6 http://udottraffic.utah.gov/CitizenReporting.aspx

7 https://www.boston.gov/departments/innovation-and-technology/city-boston-apps

8 https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/adm/fsi/en/projects/cyber/project_00025.html

9 https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/adm/fsi/en/projects/cyber/project_00025.html

10 https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/adm/fsi/en/projects/cyber/project_00025.html

11 2016, Special committee on Maintenance, repair, and strengtheing of existing concrete structures, Japan concrete institute, Maintenance, repair, and strengtheing of existing concrete structures, Journal of Concrete enginnering, Vol.54, No.3, March

12 2014, I. Iwaki, Involvement of Local Residents with Extending Service-life of Concrete Structures, Journal of Concrete enginnering, Vol.52, No.9., September

13 2014, I. Iwaki, Involvement of Local Residents with Extending Service-life of Concrete Structures, Journal of Concrete enginnering, Vol.52, No.9., September

14 2007, H. Fukumoto, Michimori Kyusyu, Proceedings of infrastructure planning 2007, June

15 http://www.qsr.mlit.go.jp/n-michi/michimori/about/renkei/index.html

1 2016. North Ireland government, RCRG household flood plan 2016, December

1 https://hanshin-exp.co.jp/company/skill/library/other/60003.html

1 https://hanshin-exp.co.jp/english/businessdomain/disaster/museum.html

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHGsROKfheo&feature=emb_logo

1 https://infra-archive311.jp/en/